The city of Arcadia, Wisconsin, population 2,400, recently became the town that roared in the immigration debate. Its new mayor, John Kimmel, barely four months on the job, made several proposals in a letter to the editor of the Arcadia News-Leader. The letter brought so much notoriety to this place, nestled in the Trempea-leau River Valley of the Coulee region in Western Wisconsin near La Crosse, that even the biggest newspaper in the state, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, actually sent reporters to venture outside the “golden triangle” (the area defined by Madison, Milwaukee, and Green Bay) to do a story on Mayor Kimmel’s proposals. Arcadia had truly made the big time.

What was so notorious about the proposals made by the mayor (who is also the owner of Arcadia’s appropriately named Detox Bar and Grill)? He argued that English should be the official language of the village. He said a local task force should forward complaints about illegal immigrants to the USCIS (formerly the INS). He thinks that local landlords should not rent their properties to illegal immigrants, and he even threatened to penalize them if they did so. He also stated that there should be some regulation on the display of foreign flags inside the village. (That would mean that the Norwegian and Polish flags that some residents fly would also be subject to regulation, which seems a bit draconian, given the ethnic heritage of the region; Mayor Kimmel himself is of German descent.)

As one might have guessed, the usual suspects had their noses bent out of joint by these proposals. But others—with substantial money, power, and influence in the community—also weighed in: They want to make sure such proposals don’t get beyond the talking stage at the common council meeting.

Arcadia is the classic company town—a throwback to the days when small and medium-sized businesses were the local safety net, before the federal government took over in 1933. The biggest company here is Ashley Furniture. Beginning as a furniture wholesaler in Chicago, Ashley built its first factory in Arcadia in 1970, saving a dying town with good-paying manufacturing jobs and with conservation and flood-control projects that tamed the Trempealeau River, which regularly flooded. Ashley also built the village a magnificent park. Memorial Park isn’t just any old Midwestern greenspace with a rusty Sherman tank and a single granite stone listing the county’s war dead. Here, there’s enough granite to build a whole state capitol, along with an M-60 tank and an F-16 fighter jet that was decommissioned and shipped to Arcadia, crate by crate, at the expense of Ashley CEO Ron Wanek. Besides the standard baseball and softball diamonds, volleyball courts, tennis courts, picnic areas, and playground, there’s the local high school’s football and track complex, the largest chicken-barbecue pit on the continent, a 2,500-seat amphitheater, and an outdoor pool and aquatic center. But the pièce de résistance is the outdoor museum, a granite structure two-miles long called the Avenue of the Heroes, detailing the history of Arcadia as well as that of every U.S. war and overseas entanglement. Inside are twisted metal beams from the World Trade Center that serve as a September 11 memorial, a statue of the early pioneers who settled Arcadia back in the 1850’s (which, according to the brochure, are fashioned to look like members of Wanek’s family), and plenty more: Washington, Jones, Lincoln, Kosciusko, Roosevelt, Pershing, MacArthur, Eisenhower, Patton, and Grant stand atop a hill called General’s Overlook, which offers a beautiful view of the surrounding countryside. Even George H.W. Bush, Colin Powell, and H. Norman Schwarz-kopf have their statues, and the Persian Gulf War Memorial also includes a monument to the first American female soldiers in combat. No expense has been spared to make this place as gaudy as you’d hope to find this side of the Potomac, and I wouldn’t be surprised if plans for a War on Terror monument are already in the works. (It will be interesting to see who gets a statue; perhaps Donald Rumsfeld?)

All this generosity to Arcadia, combined with the fact that Ashley employs 4,000 area workers at its factory and world headquarters, means that the company’s leaders are able to throw their weight around to get what they want. Former State Sen. Rod Moen found out the hard way when, in 2002, Ashley funded 527 groups (so-called soft-money PACs) that were running TV ads attacking Moen; the ads claimed the senator hadn’t worked hard enough to secure an exemption from state DNR rules that would allow Ashley to expand their facilities onto 39 acres of wetlands. Moen lost to Eau Claire Fire Department Chief Ron Brown, and Ashley soon got its exemption. Given the level of influence that the company wields, Ashley’s response to Kimmel’s immigration proposals was not encouraging:

We are hopeful that Mayor Kimmel, the Arcadia Common Council and all persons affected by Mayor Kimmel’s political statements will act reasonably, within all federal and state laws, to achieve a result that fairly and honestly respects the rights of all persons who may be impacted by the mayor’s comments.

The response of Gold’n Plump Chicken, a large food-processing plant in town, was even more negative:

It is with sadness that we watch tensions rise in Arcadia, Wis., following Mayor Kimmel’s column. We hope the community can find a peaceful and speedy resolution to this unfortunate situation.

In other words, start harassing our employees, and we will take our business elsewhere.

Immigration has become a national issue because many immigrants are settling in small towns and mid-sized cities away from the border and port areas of the country, upsetting previous cultural balances. In such places, if there’s a food-processing plant or anything that has to do with food preparation or packaging, you will find immigrants, both legal and illegal. In Arcadia’s case, they are the Mexicans and Hondurans working at Gold’n Plump. The plant was once known as Arcadia Fryers before being bought out by the St. Cloud, Minnesota-based Gold’n Plump. Today, it is a regional turkey and chicken processor, family owned by the Helgesons for the past 80 years. Unlike many others in this line of work, Gold’n Plump uses poultry raised by local farmers in its products, instead of raising the birds themselves in factory farms. However, even this small-scale operation pays the industry standard for its line of work: $9 to $11 per hour as a starting wage.

This standard was set across the state line in Austin, Minnesota, at the Hormel plant. In the mid-1980’s, Austin’s meat-packers union held a nasty strike that lasted a year and a half; the Minnesota National Guard was called up to preserve order in the town. The union was busted, and wages were slashed to their current minimums. (The Hormel strike was the subject of the documentary American Dream, which won an Oscar in 1991.)

However, there was a problem. It seems that the local workforce was not satisfied with the wages Hormel was offering workers in their slaughterhouse. Job-retention rates were low, and turnover was high, as workers decided that they could not raise their families on what Hormel and other food processors across the country were paying. So the labor market voted with its feet.

This, you might say, is a classic example of a “job Americans won’t do anymore”; after all, meat packing and food processing are not exactly glamorous. Of course, neither is being a garbage man, yet we do not hear of shortages of “sanitation engineers.” Why? Because the job pays well, as it must in order to attract and retain workers. This was once true of meat packing. However, Hormel and other such companies were caught in a vise, because, if there’s one other nonnegotiable aspect of the U.S. economy besides cheap gas, it’s cheap food. Hormel feared that raising wages would make the company uncompetitive during the commodities deflation of the 1980’s and 90’s. At the same time, the rising costs of healthcare, education, and transportation made it impossible for a single wage-earner to work there for under $15 per hour.

What was the answer to this dilemma? Import the workforce! Turn the Plains into the South Side of Chicago. Soon, food processors began spreading the word south of the border that there were good-paying jobs for all who could elude the INS. As those workers began telling their friends and family members back home about these opportunities in El Norte, the trickle became a flood. Austin and Arcadia became the beneficiaries of social engineering, courtesy of the “free market.” The food companies benefited, too, because such workers were less likely to complain to OSHA if their fingers were cut off in slicing machines; nor would the companies have to pay for years of health benefits.

No one outside of Ashley Furniture really knows how many immigrants work there; the company refuses to release such statistics about its workforce. However, there probably aren’t too many, as Ashley’s wages and work environment are still pretty attractive to local workers. But ever since the Chinese got into the furniture-making business, Ashley has found itself in the free market’s competitive vise. That is why it wanted to expand the plant over wetlands. Now, Ashley may have to slash wages in order to stay competitive. If that happens, it, too, could face the same choice that Gold’n Plump and other food companies—and construction companies and hotels and countless other industries—have had to face: Find a different workforce that will work cheap, or go under. And if Ashley goes under, it will take Arcadia with it.

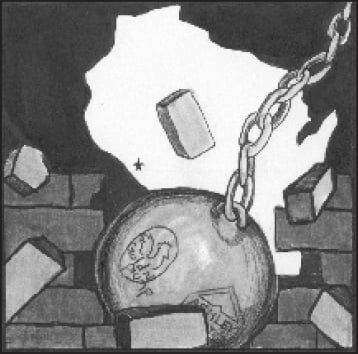

That’s why Mayor Kimmel’s proposals will get a hearing, but not much more than that. Immigration is as much a local issue as it is a national issue, and it’s a good thing to see public officials such as Mayor Kimmel take action, in the face of federal impotence. We should not forget, however, that powerful forces are in favor of unlimited immigration to, and migration throughout, the United States, and that such forces exist in company towns like Arcadia.

Leave a Reply