The Danish newspaper Jyllands Posten’s publication of the satirical cartoons depicting Muhammad prompted a crisis that touched the whole of Scandinavia. The drawings were greeted with outrage and violence from Muslims and their liberal defenders throughout the world. Danish flags were burned in Arab cities; Danish embassies were firebombed in Syria and attacked in London; and the Islamic world boycotted Danish products. Even so, the Danish government stood firmly behind the cartoonists and staunchly refused to apologize. When Norwegian newspapers republished the cartoons, there was similar government support.

Not every government in Scandinavia reacted this way, however.

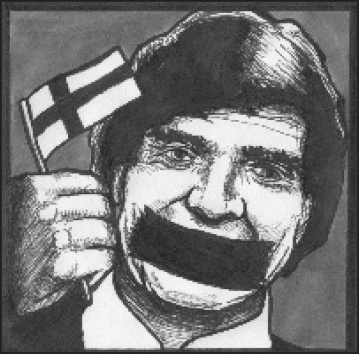

The Muhammad cartoons were never published by any Finnish newspaper. Nonetheless, in February, the Finnish prime minister, Matti Vanhanen, took it upon himself to apologize to the entire Arab world. He wanted to make it clear that the Finnish government opposed the publication of the cartoons and to distance Finland from countries, such as Denmark, that were supporting free expression. At around the same time, the website of a tiny Finnish nationalist group that few Finns had even heard of—Suomen Sisu—published the cartoons. In response, Finnish President Tarja Halonen and her foreign secretary issued public statements “regretting” their publication in Finland. Before long, the National Bureau of Investigation was “looking into” Suomen Sisu’s actions to see if they had broken a law forbidding them from “endangering the lives of Finns abroad.” The Finnish press widely regarded this investigation as pointless and condemned Vanhanen for groveling before the Islamic world. The investigation was an attempt, basically, to intimidate perceived troublemakers into silence. Then, in March, the editor of the Finnish magazine Kaltio was sacked for publishing a cartoon that satirized the government’s reaction to the whole crisis and which included a depiction of Muhammad. The cartoonist himself had his contract to draw pictures of the Finnish statesman J.V. Snellman withdrawn. This was particularly incongruous, as Snellman is an archadvocate of “free speech.” Under public pressure, this decision, by the Oulu City Council, was later reversed.

As the Finish government’s treatment of the cartoons and the cartoonists indicates, the decision by the advocacy group Reporters Without Borders to name Finland the freest country in the world for journalists is inexplicable. Finland has a long history of self-censorship, semi-dictatorship, and repression; you may exercise “free speech,” so long as you do not “rock the boat.”

Until 1809, Finland was a province of Sweden, and even now, she has a Swedish-speaking minority of about five percent who make up a large portion of the elite. From 1809 to 1917, she was an autonomous region within the Russian Empire; a few months after the October Revolution, she declared independence. In 1930, there was an attempt by the openly fascist Lapua Movement to take over Finland by force. They kidnapped a former president, opened fire on the meetings of other political parties, and were finally persuaded to back down by President Pehr-Evind Svinhufvud; the fascists propped up his government from then on. In the Winter War (during World War II), the Finns fought off Soviet invasion by violently suppressing any dissenting opinions. After the war, Finland essentially became a Soviet satellite state, though she was, in theory, still within the West. Under de facto dictator Urho Kekkonen (1956-81), criticism of the Soviet Union was basically banned, since such criticism was seen as jeopardizing the Finnish state by inciting invasion and damaging trade. Nationalist organizations and parties were outlawed. The open expression of nationalism remained illegal until the end of the Cold War. Kekkonen had the Finnish parliament in his pocket; in 1974, he decided that he did not want to stand for reelection, so he carried on as president without bothering with such a formality. Ultimately, when the Soviet Union collapsed, the Finnish economy went into total crisis.

Even now, when democracy in some form or another is seen as the ideal in the West, Finland struggles to embrace it. In 1995, when faced with a referendum on whether to join the European Union, Finns seemed uncomfortable with the idea of public differences of opinion. The tourist website Virtual Finland admitted as much:

The most recent indication of how difficult it is for Finns to tolerate differences of opinion was the referendum on membership in the European Union held in October 1994. Many Finns even felt that the division of opinion over this issue was a threat to our independence and to the future of the nation.

The Finnish people were subjected to what one professor called “a campaign of textbook Soviet Brain Washing,” and, needless to say, the government won its referendum. The leader of True Finns, Finland’s small nationalist party, claims that one of the reasons for his lack of success, compared with that of similar parties in Norway and Denmark, is the “psychological legacy of Kekkonen,” which is a reference to the notion that Finns are afraid to disagree or to be controversial.

Today, criticism of the European Union is not tolerated. Newspapers avoid publishing anti-E.U. articles or allowing True Finns any publicity. The Finnish people were not even given a chance to vote on whether to adopt the euro. Nobody, not even True Finns, dares say anything about Finland’s appalling immigration policy or discuss immigrant crime. On the rare occasions when individual politicians have voiced such criticisms, they have been derided as “racist” until they keep quiet. Finland has far fewer immigrants than Denmark or Sweden; but, as in the rest of Scandinavia, immigrants and asylum-seekers in Finland are disproportionately responsible for crime, which has significantly increased since the 1990’s, when Finland began to accept refugees from the Sudan and Somalia. Yet discussing this in the media is simply off limits. Tatu Vanhanen, the prime minister’s father, is an academic who researches race and intelligence. He recently published a book on this subject with British academic Richard Lynn and was, like Suomen Sisu, “investigated” when he reported his findings to the Finnish press. Naturally, he was deemed a “racist,” and the prime minister publicly distanced himself from his father.

Race is not the only taboo subject. There is tremendous pressure not to talk about the issue of the Swedish-speaking Finns. Despite their tiny number, they have their own schools, their own churches, their own university, their own (consultative) parliament, and their own political party, which has afforded them a tremendously disproportionate influence in almost every Helsinki government since Finland declared independence. Asserting their “rights” as a minority, they insist that everything, including movie subtitles, be displayed in both Finnish and Swedish. All Finns, whose native tongue is not at all related to other Scandinavian languages and is closer to Estonian or, more distantly, Hungarian, are forced to learn Swedish up to the university level; a certain portion of public-sector jobs are reserved for Swedish speakers; and there are areas of Finland—including towns where Swedish speakers number as little as eight percent of the population—where it is impossible to obtain work if you cannot speak Swedish. The election system is deliberately designed to gain seats for tiny minority parties, ensuring the Swedish People’s Party representation in parliament.

Even unpleasant historical events that might embarrass this minority are suppressed. During the Winter War, Finland was forced to cede Karelia (one fifth of her territory) to Russia. The huge number of refugees had to be housed somewhere in Finland, but many Swedish-speaking towns on her west coast would not let them in, lest they gain a Finnish-speaking majority. Official Finnish history books often omit this episode.

The influence of Swedish speakers is so great that almost nobody dares question their status, which was overwhelmingly reaffirmed by parliament a few years ago. Out of 200 members of parliament, only 3 True Finns opposed the measure. And laws remain on the books that make it a crime to insult or mock minorities.

Perhaps the reaction in the press to the government’s investigation of Suomen Sisu is a sign that the younger generation of Finns, who cannot even remember the Kekkonen dictatorship, are gradually coming out of his shadow. Until that younger generation is occupying the majority of seats in parliament, however, we cannot continue to lump Finland together with the rest of Scandanavia as a paragon of democracy.

Leave a Reply