Behemoth and Leviathan, the biblical chaos-monsters, are how Carl Schmitt described terra firma and the oceans in his 1942 masterpiece Land and Sea: A World-Historical Meditation. World history, he noted, is composed of land and sea powers warring against each other.

Schmitt was not the first to note this phenomenon. It has been well-documented since the fight of Athens against Sparta in the Peloponnesian War, and continues to this day in the form of the potentially fatal rivalry between America—a paradigmatic thalassocracy, or sea empire—and the tellurocratic, or land-based, China.

The route from Schmitt’s Land and Sea to a better understanding of America’s descent into insanity may not be immediately visible even to those of our readers who are familiar with his work. It exists nevertheless; a summary will make the connection apparent and reveal the prophetic character of the author’s insights.

Schmitt starts by noting that the “historical form of man’s existence” is land-based. Man’s political existence therefore also has a telluric character. The land we inhabit is crossed by borders, which separate what is ours from what is not ours. It demarcates friends from enemies, war from peace, warriors from civilians. No borders are possible at sea, however; it eludes legal certitudes and has no center.

At the same time, man is not solely the product of his physical environment. He can change it, Schmitt wrote, and he can change himself in the process. As two Protestant maritime powers, England and Holland, demonstrated in the 17th century, he can even exchange the terrestrial for a new, maritime form of historical existence.

The industrial revolution in England and its technological progress, Schmitt asserted, was due to her elite class’s decision to turn to the sea, thus starting a planetary spatial revolution. From that time forward, the British Isles could no longer be seen as part of Europe. Britain became divorced from land, deterritorialized, like a big ship afloat at sea. Her island position came to embody Britannia’s mandated mission to rule the waves. Significantly, Britain ruled the sea by proclaiming its absolute and inviolable freedom. The British thus paved the way for the emergence of a liberal, abstract, deracinated, and allegedly universal concept of freedom itself.

Oceans have no frontiers: command of the sea is not limited in the same sense as control over land. This, Schmitt noted, was the kernel of the doctrine of global interventionism. Its birth coincided with the development of the fully mature form of the nation-state in continental Europe. After the Congress of Vienna, the continental powers on one side, and Britain with her outremer heirs on the other, created two very different yet symmetrical legal orders—one of the land, the other of the sea—which gave rise to two very different concepts of warfare.

Jus publicum europaeum, or European public law, was the product of Europe’s pre-1914 land powers. State monopoly over the political processes and limited violence in the aftermath of Napoleon. Pre-1914 armed conflict was turned into the war-in-form. It rejected the notion of just war but accepted the possibility of a “just enemy,” with whom a negotiated peace is possible. For all its transgressions in the previous quarter century, France was accepted back into the Concert at the Congress of Vienna. Jus ad bellum (conditions in which countries may use armed force) and the jus in bello (regulation of warring parties) arguably were kept separate during the Crimean War and in Prussia’s wars with Denmark (in 1864), Austria (in 1866), and France (in 1870).

Britain and her transoceanic heirs accepted no such separation. For them every war they fought was a just war and therefore could not avoid becoming a total war.

Indeed, by the mid-19th century the man of the land and the man of the sea had become two very different creatures. The dichotomy demonstrated that every order is an order-in-space, that Ordnung (order) and Ortung (location) were inseparable.

To counter thalassocratic universalism and the quest for monopolar dominance immanent to it, Schmitt developed the concept of Großraum (greater space) as the building block of a pluralist, multipolar world. Even at the peak of the Cold War he was confident the temporary bipolar division of the world was not a prelude to its unity, but to a new plurality. Reflecting a new nomos, or law of the earth, he expected autonomous greater spaces would act as the restrainer of the would-be hegemon. This was both possible and necessary, because the world is a “pluri-verse” inherently opposed to the monopoly of a single power.

Schmitt traced a clear link between the nomos of the sea and the rise of free trade, capitalism, parliamentarism, constitutionalism, and the ideology of human rights. Denying the political in favor of economic and moral universalism is a maritime phenomenon; the modern itself is maritime in essence. The infusion of liberalism into the state became part tragedy, part farce. Modern societies became “liquid” like the sea itself, always on the move, temporary, unstable. The heavy is made light, the collective is individualized, identities are not firm or permanent—in the free-floating liquid world they also sail from port to port.

That is the fluid world based on the legacy of the Enlightenment, on the view of man as a fully autonomous subject independent of all natural, religious, and historical restraints, capable of constructing his own reality and constantly reinventing himself. Man’s separation from land and his turning to the sea morphed into an emancipatory project based on individualism, universalism, and progressivism. Totalitarian tendencies were always immanent to this endeavor. It cannot but criminalize every enemy, foreign or domestic. It knows no physical frontiers, it accepts no limits.

In the end Schmitt’s Land and Sea enables the reader to comprehend the organic link between liberalism, economic globalization, and the intersectional leftist ideology of our own time. The connection is neither accidental nor temporary. It is evident in the American corporate elite, which monolithically and enthusiastically sides with the postmodern left with which it shares the same genes. That sordid spectacle demonstrates it is not possible to be a social and cultural conservative supportive of traditional institutions, mores, and beliefs, and at the same time to be a pro-free market, free trade liberal in the sphere of economics.

It is not possible to be a conservative and yet to justify America’s planetary interventionism and pathological quest for global hegemony. The rhetoric of the “old left,” its opposition to economic globalization, domestic inequality, and declining real wages, is just as meaningless if it simultaneously supports multiculturalism, open borders, mass immigration, universal human rights, identity politics, and “humanitarian interventions.”

Almost eight decades after Carl Schmitt published Land and Sea, his message resonates with those who believe the game is not up. A legitimate international order needs to accept and integrate a plurality of political communities with different, self-determined domestic political identities.

That order also has to recognize as rightful the jus ad bellum, which belongs to all functional political communities. A model of international order that violates either of these two conditions would be detrimental to the survival of those communities, and therefore illegitimate. Wars distinguished by absolute enmity will continue for as long as one great power, or several among them, follow universalist ideologies which reject the spatialization of political conflict.

The United States is clearly the only major power in today’s world which resolutely rejects all forms of spatial realism. America is the only major power which insists on a deterritorialized, purely ideological, openly hegemonic definition of its interests, which now include the promotion of LGBTQ+ “rights.” Having declared America the leader of an imaginary international community in the 1990s, foreign policy decision makers in Washington developed a mindset, and adopted strategies and policies, which William Kristol and Robert Kagan have hubristically characterized as America’s benevolent global hegemony. In reality it is postmodern power politics on steroids, awkwardly masked by the rhetoric of “promoting democracy” and “protecting human rights” ad nauseam.

Hubert H. Humphey, Lyndon Johnson’s vice-president, once said “foreign policy is really domestic policy with its hat on.” Many theorists would agree, but the ongoing domestic transformation of the United States indicates this is a two-way street. In line with Schmitt’s analysis, it seems plausible that America’s quest for global hegemony over the past three decades has facilitated the erosion of liberties and the rise of destructive ideologies at home.

History teaches us that when republics become empires, decadence and collapsing standards are inevitable. The Roman Republic was a strong community based on the agrarian virtues of honor and patriotism, totally unlike Edward Gibbon’s depiction of late imperial Rome, its inhabitants sinking “into a vile and wretched populace,” eventually snuffed out “if it had not been continually recruited by the manumission of slaves, and the influx of strangers.” Gibbon concludes that “it was the just complaint of the ingenuous natives, that the capital had attracted the vices of the universe, and the manners of the most opposite nations.”

This is “diversity” gone berserk, lethal to the host organism and to its invaders in equal measure. This is today’s America.

The de-territorialized, ideologically messianic paradigm of the neoconservative-neoliberal duopoly will continue to prevail for years to come, to the detriment of real people and real communities everywhere. It will deny the legitimacy of any polity not subjected to its own writ, indoctrination, and punitive control.

The same establishment which stole the 2020 election—relying on the same permanent-state apparatus—will continue to present the greatest single threat to the shrinking remnant of republican liberty at home, to peace and stability abroad, and to the rationally defined American interest everywhere.

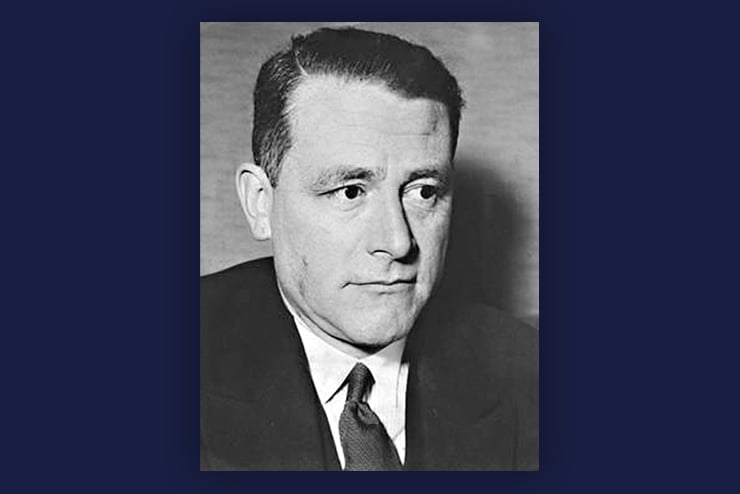

Image Credit:

above: Carl Schmitt (Wikimedia Commons)

Leave a Reply