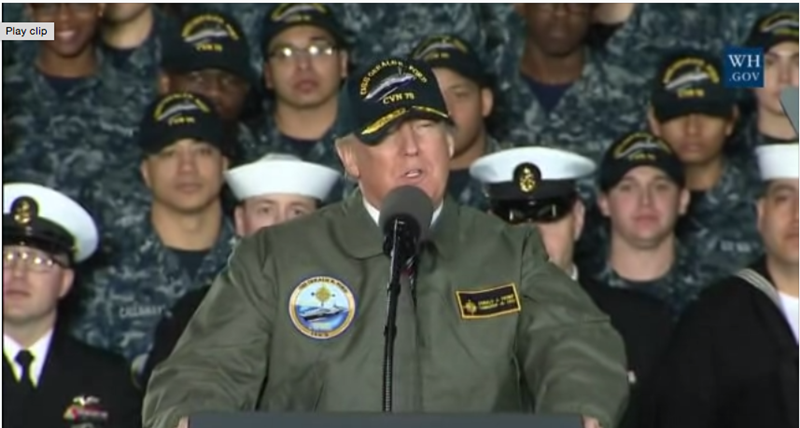

On March 2, standing on board the USS Gerald R. Ford—the most expensive warship ever built—President Donald Trump touted his $54 billion military spending increase. A disproportionate part of that immense sum (more than the total defence budget of Russia at $45 billion, or India at $53 billion) would go to the Navy, eventually increasing its current 275-ship fleet to 350 vessels of all types and sizes. Trump said these warships would be used to “project American power in distant lands.”

The first problem with Trump’s stated intent to have a twelve-carrier navy “we need”—capable of “facing any threat”—is that he has not defined this formidable force’s mission. Without a clear statement of strategic doctrine, the “need” and the “threat” are but amorphous rhetorical devices. It is unclear what need would a 350-ship Navy with 12 carrier groups achieve that has been out of reach of its 270 ships and ten carriers. If the objective is simply to enhance global hegemony (“primacy”) and to be able to intervene in distant lands at will, then President Trump intends to follow his four immediate predecessors in the bid to maintain full-spectrum dominance. This would be a radical and regrettable departure from his campaign pledge to shake the rust off America’s foreign policy and to base it on the rational principle of national interest.

The second problem is that an additional $54 billion in defence spending for FY 2018 may not be enough to cover the shipbuilding program and to provide for adequate maintenance of the existing fleet, which has been overused for decades. Since the late 1990’s the Navy has kept a hundred ships continuously at sea, and each of them is deployed for at least six months at a time. This has created immense maintenance and reliability problems. Additional funds would be better used to properly maintain and upgrade the existing 270-ship Navy, and to reduce such extensive, world-wide deployments. That brings us back to the core issue of mission and strategic doctrine, however: what is the “need,” how to define “threats,” and how to match goals and capabilities. The strategic failures in Afghanistan and Iraq were never due to the shortage of ships. By contrast, Russia was able to turn the tide in Syria with a few dozen planes and minimal naval deployment.

The third, closely related problem is that the Navy’s mission in the decades ahead should be focused on enhanced capabilities, not on total ship numbers. The continued focus on aircraft carriers is especially problematic in view of the rapid development of anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) weapons. Both Russia and China have been developing layered anti-ship and anti-aircraft defenses that would make it more difficult for the U.S. Navy to operate closer to their shores, and latest long-range anti-ship cruise and ballistic missiles make carriers vulnerable even far from those shores.

Some defence analysts suggest that carriers are becoming as obsolete as the battleships which they so decisively put out of business during World War II. It is no longer certain that a massive, massively expensive mobile air base is the key to winning future battles and projecting power. A 2015 study by a former Navy officer strongly argues that carriers are based on outdated abilities. Their strike aircraft have spiraling price tags and increasingly short range: from a thousand miles that a Vietnam-era A-6 Intruder could fly loaded with weapons to a little over 500 miles for today’s F/A-18 Super Hornetand tomorrow’s F-35C. The consequence is that in order to launch their manned aircraft, our present and future carriers would have to sail 500 miles closer to the enemy shore than their 1960’s predecessors, making them increasingly vulnerable to long-range drones and ship-killing missiles. China’s “supercarrier killer” DF-21D ballistic missile has a range of 1100 miles. A dozen or more could be fired simultaneously at a prime target like a Ford-class carrier in a lethal “sea swarm” attack. If the risk of this happening is considered too great, the carrier will be kept out of the potential no-go zone, such as the South China Sea; but its aircraft will not be able to reach their targets, making the carrier useless.

Traditionally a telurocracy, China is rapidly developing a first-class navy parallel with its advanced A2/AD arsenal. It has progressed from green-water to blue-water fleet in only two decades and now ranks second in the world. History teaches us that no power has been able to maintain naval supremacy indefinitely. “Power projection in distant lands” has been the purpose of a powerful navy ever since Athens converted her leadership in the wars against Persia into outright hegemony a generation later, but every form of thalassocratic monopoly has been impermanent. When Spartans learned to sail in the closing stages of the Peloponnesian war, and closed the Athenian grain supply chain at the vulnerable choke point of the Dardanelles, the game was up. The Roman Republic was a land power forced to acquire the art of seafaring during the Punic Wars – eventually turning the tables on Carthage, previously a naval hegemon. The Arabs came from an arid, landlocked desert; but within a century of their prophet’s call to arms, they successfully challenged the Byzantines’ mastery of the Mediterranean. The Turks likewise came to Asia Minor from the steppes of central Asia as horsemen, yet by the time of Suleyman their mighty navy was able to winter at Toulon. Britannia ruled the waves for over two centuries, but the Royal Navy is now a shadow of its former self.

As a great trading and military power separated from the Eurasian land mass by two oceans, America needs a navy capable of “facing any threat”—rationally defined—but not a navy tasked with enforcing an open-ended geopolitical status quo in every corner of the globe. A new strategic doctrine is needed, suited to America’s post-hegemonistic role in a multipolar world. Expensive and vulnerable carrier strike groups are not the right tool for that role. They are outdated technologically, operationally and conceptually. Not the right way to put America first.

Leave a Reply