Decades provide a useful, if not infallible, structure for organizing and understanding our historical experience. However frayed and disputed their limits, terms like “the twenties,” or “the eighties” each conjure their particular images and memories. Whatever we call the decade we have just completed—the twenty-teens?—it is one with landmarks arguably as important as any in our history.

Globally, any glance back over the past decade must give a central role to the rise of China. Over just ten years, its economy more than doubled in size, to rough equivalency with the United States, and it continues to grow. China also began aggressive military and diplomatic expansions into its neighboring territories and seaways. Since taking power in 2013, President Xi Jinping has triumphantly succeeded in his campaign to Make China Great Again. This will set the world’s political agendas for decades to come.

Within the United States, historians will long study the year 2016, and not just for its wildly divisive politics. Whatever their own ideological slant, they will explore that year’s presidential election for what it revealed about the radically different economic paths taken by parts of the United States, and how those schisms manifest in culture. Between Red and Blue, coastal and heartland, and old and new economies, there is a fundamental dispute about the American identity. However future elections play out, 2016 will continue to be symbolic. Love it or loathe it, “Trump’s America” will endure in historical analyses.

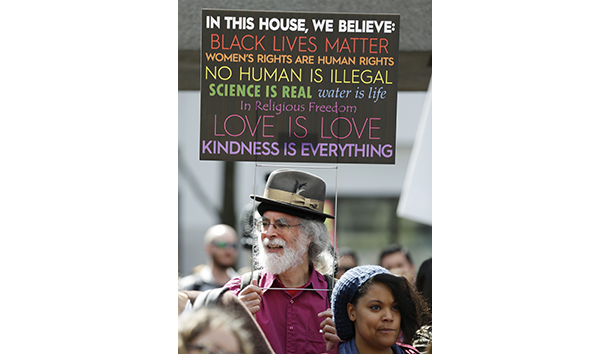

“The sixties” is now a staple of curricula, and that decade offers a frequent reference point in political debate. But we can now legitimately ask whether the innovations and radicalism of the 1960s were any more influential than the past decade. What did 1968 have that, say, 2015 did not? Mass racial movements and urban protests such as Black Lives Matter, a radical feminist upsurge, college authorities losing control to militant mobs, radical environmentalism… Yes, the ’60s riots were much larger and bloodier, but that is more a function of changes in police tactics than in the degree of anger of the insurgent crowds.

Arguably, the wide-ranging radical movements of the mid-twenty-teens not only took up the causes of the late 1960s, but actively pushed them to further and more absolute conclusions. Nobody in 1968 seriously contemplated the wars over history that would sweep away Confederate flags, statues, and symbolism, yet that has been accomplished thoroughly since 2015. Few ’60s feminists dreamed of establishing their particular definitions of sexual violence and aggression as mainstream social orthodoxy, still less of turning that fury against powerful men in politics and mass media. But this was accomplished by the last decade’s #MeToo movement.

Let me propose a theory of historical development: 1968 was the blueprint; the twenty-teens were the implementation. The last decade, in fact, emerged as one of those major periodic waves of radical fervor to which the U.S. is so prone, and is at least on a par with the 1840s or the 1960s.

To take another case in point, has any radical movement in U.S. history ever accomplished a more sweeping and thorough restructuring of our most basic assumptions about gender, family, sexuality, and—yes—about human nature than the move to legitimize same-sex marriage? Even a decade ago, many liberal politicians were timid about publicly affirming their support for the idea. That has totally changed since the 2015 Obergefell v. Hodges decision by the U.S. Supreme Court. Today, same-sex marriage is thoroughly mainstream, to the point that many younger adults wonder why it was ever controversial. That is a definition of revolution: when the world has changed so utterly that the older world can no longer be comprehended.

Just as conservatives were reeling from Obergefell, another and arguably still more extreme social revolution hit them in the form of transgenderism, with all the limitless legal and ethical consequences that entails. If not wholly invisible, only a decade ago transgender concerns had nothing like the visibility they have today. That changed almost overnight with two unrelated mid-decade events. One was the publicity accorded to athlete Bruce Jenner’s transition to become the “trans woman,” Caitlyn; the other was the Obama administration’s demand that schools recognize and defend the rights of transgender students. The transgender revolution is now officially under way. Anyone who believes it can be limited or accommodated should pay close attention to the total success of the same-sex marriage campaign.

As public servant John W. Gardner wisely observed, “History never looks like history when you are living through it,” but history it is, nevertheless. We are living through history, and we are indeed living through an era of authentic revolutions. If you think that everything that matters in the world is being transformed overnight, you are probably right.

Leave a Reply