Nope

Directed and written by Jordan Peele ◆ Produced by Jordan Peele and Ian Cooper ◆ Distributed by

Universal Pictures

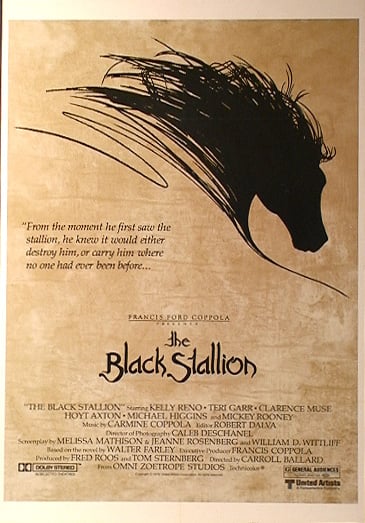

The Black Stallion

Directed by Carroll Ballard ◆ Written by Melissa Mathison, Jeanne Rosenberg, and William Wittliff, after the novel by Walter Farley ◆ Produced by Fred Roos, Tom Sternberg, and Francis Ford Coppola ◆ Distributed by United Artists

To put Jordan Peele’s new film, Nope, into perspective, it’s useful to recall his first two films, Get Out and Us. Both caused considerable controversy and established Peele as a director addressing racial discord in America.

Many considered Get Out a racist assault on whites. In my 2017 review of the film, I disagreed. I thought the film was an inspired satire of American race relationships with a Frankensteinian premise, one in which wealthy whites are so envious of black talent and physical prowess that they kidnap them for the purpose of acquiring those talents for themselves. I took this to be a spoof on liberal whites so eager to display their moral superiority that they are forever falling over themselves to demonstrate their admiration for blacks, especially downtrodden ones.

Peele’s second film, Us, seemed to prove me wrong. This film is an unmistakably bitter allegory about white culture’s supposed assumption of racial superiority. Such a message won enthusiastic kudos from the unofficial academy of Right-Thinking Film Reviewers (RTFR).

Beneath the silly Invasion of the Body Snatchers-style sci-fi plot, the thematic premise of Us is that blacks have literally split into two subgroups. There are the assimilationists, who do all they can to imitate whites, and then there are the angry blacks, called the “tethered,” who want vengeance for having been relegated to a demeaning position in American society. To gain this vengeance, the tethered are ready and willing to kill not only whites but, even more so, the blacks who have chosen to collaborate with whites in order to live more comfortably and gain the kind of education that leads to success in “white” professions. The tethered consider these blacks to be traitors who need to be executed as brutally as possible.

Us ends with a full-out race war in which the tethered blacks slaughter their enemies, both white and black, without compunction. The tethered arm themselves with “white” tools: scissors and golf clubs. Why scissors? Because they are the emblem of the tethered’s intention to cut themselves off once and for all from the their traitorous brethren. The golf clubs serve notice that blacks have had quite enough of whites’ country-clubbing privileges, which, as often as not, are supported by black labor: waiters, garage men, maids, and such.

The RTFR couldn’t get enough of this. Richard Brody, of The New Yorker, inanely hailed the film a “colossal cinematic achievement,” whereas I would describe it as a colossal failure filled with mismatched cuts, unexplained character appearances, and brazen non sequiturs in the service of a story that defies all logic and sense.

Productions)

Nope carries on with Peele’s racial grievance. The narrative opens with a brother and sister, OJ (played by a stolid Daniel Kaluuya) and Emerald (a winningly vibrant Keke Palmer). They have inherited their father’s successful horse wrangling business serving the needs of Hollywood filmmakers. We watch the siblings making a pitch to some Hollywood executives, aiming to assure the big shots that they will continue providing their father’s service. A judiciously calm OJ presents the facts. Like their father, he tells his audience, he and his sister have the wherewithal to do the job. To his annoyance, however, the big shots pretty much ignore him. One of the more empathetic comes over and whispers to him, “It’s not time yet.” Although OJ doesn’t say the words, you know what he’s thinking: “Not time? Then when will it ever be time?”

Disgusted by the response he gets, OJ halts and turns the proceedings over to Emerald, who tries a different tack. She begins by telling the executives her family’s history, first showing the famous 1878 film clip of a black jockey riding a stallion. This is reputedly the first instance of film displaying movement on screen. She turns to the executives, noting that everyone in the film business knows this clip, but, she asks, do any of you know the name of the jockey? Of course, they don’t. She, on the other hand, does. It was her great, great grandfather.

The executives, however, remain visibly unimpressed. After the meeting, the siblings return to their horse farm: OJ to ponder and Emerald to devise new approaches to their problems, the primary of which is keeping up with the farm’s mortgage. OJ proves his professional expertise by mounting and riding a bay at breakneck speed around the farm. When he stops, you can see in his face the growing suspicion that racism is challenging their future.

But this isn’t OJ’s only problem. He’s also preoccupied with a huge flying saucer unaccountably hovering over his ranch. The saucer has an ominous black maw in its center, which will later suck OJ inside, where something or other happens to him. We never learn what, much less why.

So what’s going on? OJ and the film keep their counsel. I’m as tolerant as the next fellow of enigma in fiction, but by the 60-minute mark, my patience had run out. I was ready to shout at the screen: “What the hell is the point?” Only my professional politeness prevented me from doing so. Why, I wondered, did Peele think this opening would hold his audience? All I can say is that it didn’t. I and the audience around me grew increasingly restive as the minutes clicked by.

For its 125 minutes of running time, nothing much happens in this film. And then it ends suddenly, leaving a walloping sense of pointlessness in its wake. As nature abhors a vacuum, so film, the vital art, abhors inertia. With neither stress nor challenge, film narratives simply do not make an impression and are thus ignored.

And yet, Nope has been praised by quite a few RTFRs. This is puzzling given the film’s obvious weakness, unless we factor in an emperor’s-new-clothes policy being extended to black filmmakers as a matter of political courtesy. If this is the explanation, I’m afraid it will do a disservice to Peele’s professional future. He’s not without talent, but if he accepts such tributes as genuine appraisals of his merits, he may never experience the challenge an artist requires to develop his nascent abilities.

Titling this film Nope does little to advance its cause. In fact, given what we see on the screen, the title seems to confirm a sense of surrender rather than a spirit of accomplishment. One more issue. If you want to entice an audience, it’s a good idea not to name your putative hero after the murderous thug O. J. Simpson. People may get the wrong—or possibly the right—idea about your intentions. In short, there is every reason to say nope to Nope.

poster (image via American

Zoetrope)

To be fair, Peele did succeed in reminding me of a much better film that features at least one horse. In 1979, Francis Ford Coppola’s protege Carroll Ballard made The Black Stallion, an exceptionally beautiful adaptation of Walter Farley’s 1941 novel. The film tells the story of a 10-year-old boy and a horse shipwrecked together off the coast of North Africa. Kelly Reno played the boy, Alec Ramsey, who first befriends and then saves the horse, named Bucephalus, after Alexander the Great’s legendary steed. The boy and horse manage to survive their castaway ordeal by coming to one another’s rescue as they eke out sustenance on an uninhabited, sun-bleached island until they’re rescued by passing fishermen.

I don’t know how to classify this film. It’s not exactly a fantasy. Its first half has more in common with lyric poetry than with narrative; the scenes of Alec riding the Arabian stallion bareback across the beach and into the waves are simply wondrous. Then midway through, it becomes a heroic adventure. The stallion and Alec are brought home, where they are welcomed with the acclamation of his town. He and his mother keep the stallion in their backyard until an aging jockey (Mickey Rooney—precisely the right actor) learns of the horse and its phenomenal speed. Then the inevitable happens.

The jockey and his track associates decide to enter the horse in a race. Knowing Alec’s special connection to the stallion, they, of course, want the boy to ride him in the contest, despite the risk and illegality of doing so. By this point, the denouement is at once as preposterous as it is predictable. After all, would track officials countenance a 10-year-old riding a stallion in a professionally organized race? But you’re not at all troubled by this bit of malarkey. Instead, you’re carried away by the thrill of watching it take place.

More thrilling than the film’s inevitable outcome—or, for that matter, anything else in its narrative progress—is the sheer beauty with which cinematographer Caleb Deschanel invested the film. His superb care and uncanny energy in creating the visual component of the film are absolutely peerless. I could go on waxing rhapsodic about Deschanel’s craft, but some things simply do not transfer well from screen to page. Instead, I’ll stop here with simple encouragement: I urge you to see this film if you haven’t or to see it again if you have. No noping about it: I guarantee you won’t be disappointed. ◆

Leave a Reply