I’ve been kickboxing at the gym here in the Alps. Well, it’s one-way kickboxing; I punch and kick, my opponent holds up pads and doesn’t punch or kick back. So, it’s rich man’s kickboxing, but great exercise. Great, at least, until a trainer began to blast rap music. I stopped my pummeling to ask for a change. “Try Culture FM,” I told him. The trainer complied, and suddenly a Schubert scherzo had me floating like a butterfly and stinging my trainer with newfound energy.

“That’s music for old men!” yelled a nearby roughneck. It turned out to be my boy, who will be 40 this year. Although he can easily take me in a fight nowadays, he still ran out of the gym when I pretended to attack him for what he had said.

Now, you cannot have too much of Schubert any more than you can have too much of a clear, sunny day in the mountains. His unlimited range, his power rooted in the primal facts of Western music—the word “majestic” does not do him justice. But start playing some Schubert in New York’s Central Park and count the minutes before some thug tells you to try rap.

Nevermind! Space does not permit me to go on about how great and uplifting classical music can be to one’s body and soul: Chopin’s amazing melodies, Wagner’s and Verdi’s seriousness of purpose and temperament for the theatre, the incomparable beauty of Beethoven’s cycle, the miraculous genius of Mozart. Neither will I go into the brain-jolting cacophony of what passes for music today, no, nor the horrors of rap’s N-word-slinging, women-degrading, gun-praising dissonance.

Instead, I will tell you how lucky I was to have been young during the golden age of American popular music, which ended with the rise of rock in the late ’60s, just as I was turning 30. George Gershwin and Cole Porter were sublime, along with such giants as Jerome Kern, Oscar Hammerstein, Richard Rodgers, Alan Jay Lerner, Fritz Loewe, Irving Berlin, Johnny Mercer—I could go on and on.

Am I a nostalgist pining for a vanished age? Of course, but what’s wrong with that, in view of the utter horrors we hear nowadays? Where will you find today such clever lyrics as “You’re the Top,” by the great Cole, or as brassy a song as “You’re Just In Love,” from Berlin’s Broadway musical Call Me Madam. After I saw the incomparable Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers dance to Berlin’s “Cheek to Cheek,” that song became my favorite. When I was not yet 20, I happened to play tennis with a beautiful woman named Rita, who was the separated wife of the great musician Hoagy Carmichael. His song “How Little We Know” could break one’s heart.

The first Broadway musical I saw was South Pacific. I was on Thanksgiving break from my prep school and fell madly in love with Mary Martin, who played the nurse romanced by the ageing Italian opera singer Ezio Pinza, in the role of the plantation owner, Emile. One of the songs, “Younger than Springtime,” haunted me for the rest of my school years.

My father used to get tickets for musicals whenever I was home from school, so Carousel, The King and I, Oklahoma, Anything Goes, Bells Are Ringing, Guys and Dolls, and Kiss Me, Kate were some of the spectacles I enjoyed. I was always in love then, because the music I was listening to was all about love. Today on Broadway, it’s all about visual dazzle and electronic tricks.

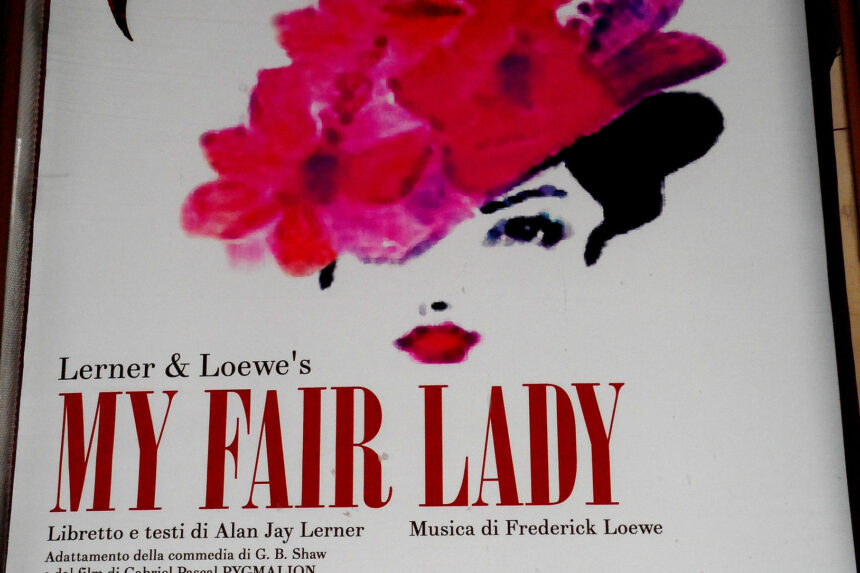

In 1956, I saw My Fair Lady, in which Julie Andrews and Rex Harrison delivered rapid-fire discourses. Hammerstein had said that Pygmalion could not be done as a musical, since Shaw was too prolix. But Alan Jay Lerner did it, and how! A few years later, 1964 to be exact, Jackie Kennedy’s younger sister, Lee Radziwill, and I were painting the town red. We ended up in El Morocco, the best and plushest nightclub in Manhattan at that time. As we were seated, I noticed next to us a couple who smiled and were not practicing the studied detachment of the so-called society folk of that time. The man oozed cosmopolitan sophistication, and he asked me how I got the black eye I was sporting (from boxing the day before).

It turned out to be Lerner, who composed the librettos for such great hits as Camelot, Gigi, An American in Paris, Brigadoon, Paint Your Wagon, and, of course, My Fair Lady. After many drinks, he asked Lee and me to come back to The Pierre, off of Central Park, and hear the new score he was working on. Seated at the piano in the hotel’s penthouse, he sang “On a Clear Day You Can See Forever.” Lee and I tripped over ourselves with praise. He then invited me into the next room to deliver some fatherly advice: “You are a nice looking young man; boxing is too brutal a sport.” He then gently removed his glass eye and said, “I got this boxing.” And just as gently, he put it back in.

We stayed until 5 a.m., and it remains an unforgettable evening. I never saw Lerner again but recently read that he married eight times. Eight lucky women, as far as I’m concerned. ◆

Leave a Reply