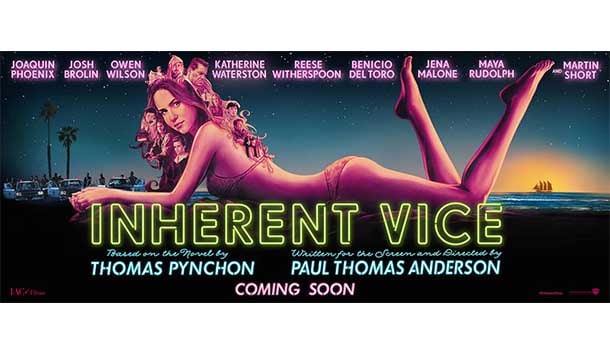

Inherent Vice

Produced and distributed by Warner Brothers

Directed and written by Paul Thomas Anderson, based on the novel by Thomas Pynchon

Birdman

Produced by New Regency Pictures

Directed and written by Alejandro González Iñárritu

Distributed by Fox Searchlight Pictures

You never know what you’ll learn at the movies. Watching the two films under review this month, I discovered solipsism isn’t, as I had thought, a philosophical school of thought, but a disease spread by smoking marijuana while taking yourself much too seriously.

Inherent Vice and Birdman both feature irremediably self-involved protagonists who, under the influence of cannabis, concur with Bishop Berkeley that esse est percipi, or, translating loosely, the external world exists only in their minds. True, neither articulates this idea. They would have to be decently self-aware even to entertain it, which they demonstrably are not. What they are is self-consumed, as anyone familiar with the effect of cannabis would recognize. For those who are unacquainted with this drug, the films thoughtfully provide primers by cinematically inducing a state of mind similar to that experienced under the influence of THC.

Inherent’s director Paul Thomas Anderson does this by rigorously following the peregrinations of his stoned protagonist Doc Sportello (Joaquin Phoenix) in his adaptation of Thomas Pynchon’s 2009 novel of the same title. Sportello is a pot-smoking private detective who’s attempting to unravel a prototypical L.A. noir mystery. There’s not a scene in which he doesn’t appear front and center, unfortunately. It’s 1970, so naturally he natters on about the Manson Family’s trial, the evils of President Nixon, and the importance of combing the stems and seeds from the weed he smokes incessantly. In short, he’s a left-wing hippie dunce. This would be fine if Pynchon and Anderson gave any indication that they consider their creation a tedious loser. But they think he’s groovy, an adjective they must consider cool, given the frequency with which their hero uses it.

When we first meet Sportello, he’s conversing with his ex-girlfriend Shasta (Katherine Waterston)—possibly named after California’s active volcano, or maybe the soda popular at the time; it doesn’t seem to matter which. She informs the glazed and dazed private eye that she’s having an affair with the considerably older Mickey Wolfmann, a local real-estate developer of questionable ethics. (Or is that redundant?) Wolfmann’s wife, who is herself conducting an affair with a younger man, is plotting to put her hubby in an insane asylum in order to get at his prodigious bank account. Shasta thinks they want her to help. Might Sportello look into it? After all, he’s got friends in the D.A.’s office. Is Shasta angling to turn state’s evidence? Is California sunny? One thing leads to another, and Sportello finds himself being thrown about, literally, by his old nemesis, Lt. Det. “Bigfoot” Bjornsen (Josh Brolin). I’ll remember Bigfoot carrying Sportello around like a parcel for many years to come.

One thing to be said in favor of the film: It rarely strays from Pynchon’s text. That can also be said against it. Anderson has treated Pynchon’s narrative as if it were biblically sacrosanct instead of a lame pastiche of left-wing paranoia. It’s the shaggiest of shaggy-dog stories, in which character and event take a distant second place to Pynchon’s episodic riffs on America’s national decline, with something called the Golden Fang being Exhibit A of his indictment. The Fang is variously a pirate ship used to smuggle dope, a tax shelter for billionaire dentists (get it?), and, possibly, a covert arm of the CIA. Of course, we never find out. As in the novel, the conceit floats around aimlessly, and then submerges in the L.A. murk. But not before we encounter its most daring incarnation in an office building fronted by a 30-foot-high gold-tipped fang made of weather-resistant resin. The building houses a tax shelter for dentists run by Dr. Blatnoyd, a coke-sniffing member of his profession played with wonderful lunacy by Martin Short, who provides the only laughs in this otherwise limp satire.

Sportello becomes embroiled in a series of plots that never quite come to a conclusion. There are corrupt cops, clueless FBI agents, and devious assistant district attorney Penny Kimball, played by the ever-resourceful Reese Witherspoon. As unlikely as it sounds, all these souls look to Sportello to find Wolfmann when he goes missing from his latest property, Channel Vista, a deeply illegal condo development he has Bigfoot hawking on late-night television. The development proudly takes its name from the waste canal it overlooks and, one infers, oversmells.

There’s not much else to say about this lazy parody of film noir. Anderson, under the influence of Pynchon, can’t be bothered to provide a convincing denouement. It just wouldn’t be groovy.

If there’s a purpose or theme in this film, it’s Sportello’s rueful reflection that the forces of corporate greed have co-opted the idyllic sensibility of the 60’s. There’s no indication of irony in his proclamation, so I suppose we have to accept that Sportello is speaking for Pynchon. Wow! That’s not groovy at all. Well, what can you expect of a work entitled Inherent Vice, a term from maritime law. It refers to shipboard merchandise that can’t be insured because it is naturally prone to irreparable damage—like, say, marijuana, or like humans under the mark of Original Sin?

In Birdman, Mexican director and writer Alejandro G. Iñárritu also plays the solipsistic hand and ups the ante considerably. He films his protagonist Nick Riggan (Michael Keaton) in nearly constant close-up. What’s more, his camera tracks him continuously so that the film seems to be a single 119-minute take. Alfred Hitchcock tried something similar in his 1949 Rope, but his experiment was limited by the filmmaking technology of his time. He was recording action on ten-minute film reels, and he had to pause every nine minutes or so to change canisters. With a digital camera, there are no reels, so Iñárritu’s cameraman, Emmanuel Lubezki, was able to shoot continuously, or nearly so, within a single set with almost no montage editing. This makes the resulting movie both a propulsive and an immersive experience during which we’re encouraged to identify willy-nilly with Riggan as he moves headlong through space and time. This is the film’s most interesting aspect.

Unlike Sportello, Riggan, who drags on a joint only once in the film, doesn’t seem to be a marijuana addict, but, like the standard-issue pothead, he’s thoroughly consumed with himself. He is a demoralized film star who 20 years earlier had played the lead in a billion-dollar superhero franchise. Winged, feathered, and beaked, he was the incarnation of Birdman. Then, mysteriously, he refused to appear in the series’ fourth installment. The parallel with Keaton’s involvement with the Batman series, from which he bailed in 1995 after two outings, is, of course, deliberate. It gives Birdman its metafictional frisson, as they say.

Since his Birdman days, Riggan hasn’t been out of work exactly, but neither has he prospered. His roles are fewer, his paydays smaller. The dwindling portion of the public that cares at all now thinks of him as a 63-year-old has-been who once thrilled them in the multiplexes. His personal life has also hit the skids. He’s divorced with one child, a snotty 20-year-old daughter (Emma Stone in a tailor-made role) who’s been in rehabilitation for addiction to marijuana. (Do people need rehab for marijuana?)

When we first meet Riggan, he’s seated in the lotus position levitating two feet in the air. We watch him from the back as a voice asks, “How did we end up here? . . . This place is a shithole.” Shortly afterward, we discover that Riggan is in a changing room of Broadway’s St. James Theater. He’s in the process of trying to revive his acting career by mounting his own adaptation of Raymond Carver’s short story “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love.” He means to prove himself a genuine artist by directing the piece and performing the lead role. It’s “ambitious,” as Edward Norton, playing one his costars, laconically observes. It’s also wildly impractical. Carver wrote about alcoholically depressed losers, and while some of his work effectively renders lower-middle-class American life, little of it lends itself to the stage, especially the quietly somber “What We Talk About.”

So the stage is set, figuratively and literally. We follow Riggan as he rehearses with his cast. Along the way, we learn that, like many another actor, he’s possessed of an ego that is at once impossibly vain and utterly fragile. Sometimes he’s convinced he is in control of all he surveys; at other times, he’s nearly prostrate with fear of failure. He’s subject to delusions in which, at the snap of his fingers, he can send objects through the air, explode buildings, and effortlessly fly over Manhattan as would any other superhero. Whenever he loses confidence, however, he’s liable to fits of jealously and freakish misadventures, such as stumbling out of the theater in his underwear.

Iñárritu clearly wants to make a statement about what used to be called the human condition, which includes unwieldy oscillations between feelings of grandeur and desolation. He’s chosen to exemplify this experience with the performer’s unsettling experience of moving between theatrical and ordinary life. Why? I suspect it’s because actors—even method actors—are paid to exaggerate their feelings so that audiences can appreciate their significance and universality. Iñárritu and his cast do this very well, but there’s a problem, and anyone who has spent some time with actors will know what it is. Offstage, where most of the play is supposed to be taking place, actors are likely to be bores. The film’s players perform accordingly. Their “real” selves are tedious. They can’t stop performing. They’re so insecure that they feel compelled to impress everyone in the room. They grow petulant whenever attention wanders from them. Keaton, Edward Norton, Emma Stone, and, perhaps the film’s standout, Amy Ryan (playing Riggan’s ex-wife) do this exceptionally well. Unfortunately, watching actors play everyday selves isn’t all that interesting, even when their kitchen sink travails are relieved by moments of narcissistic fantasy. Finally, you can’t help thinking the movie isn’t about much beyond the inflated thespian ego. As such, it’s an unquestionably superior acting exercise, but, when all is said and done, the play’s the thing, and there’s not much of one here. Still, it’s worth a couple of hours of your time, especially if you like these performers and film experiments.

Leave a Reply