The Eagle

Produced and distributed by Focus Features

Directed by Kevin Macdonald

Screenplay by Jeremy Brock

There’s this to be said for director Kevin Macdonald’s The Eagle, set in Roman-occupied Britain circa a.d. 140: It’s remarkably unpretentious. It was made for a mere $24 million at a time when even the most ordinary Hollywood romantic comedies cost two to three times as much, and, what’s more, it seems entirely free of CGI effects. The Eagle is that odd bird—a film distinguished by its aesthetic and budgetary restraint.

Macdonald and screenwriter Jeremy Brock adapted their film from Rosemary Sutcliff’s 1954 novel The Eagle of the Ninth, which tells the story of what may have happened to Rome’s Ninth Legion: Supposedly, it disappeared into the wilds of barbarian Caledonia—today’s Scotland—in a.d. 117, never to be heard from again. Today’s historians dispute this account, but it used to be accepted and was thought to have been so embarrassing that, in 122, Emperor Hadrian angrily commissioned his famous wall running from the North Sea to the Irish Sea, much of it still standing today, although in notable disrepair. As far as the Romans were concerned, the wall marked the end of the world worth having. The tribes above were to be left to their vile, barbarous stupidity, and good riddance. Sutcliff, who specialized in historical fiction for young people that appealed to adults as well, imagined that the lost legion’s leader would have been held in contempt for having succumbed to what could only be surmised to have been a barbarian slaughter. She further imagined what this contempt might have done to the fallen leader’s son. Having speculated thus far, she had her story.

The fictional son, Marcus Flavius Aquila, follows his father’s lead. He joins the army, rises through the ranks, becomes a centurion, and then wangles a despised posting, the command of a plain wooden frontier fort south of Hadrian’s Wall, the fort in which his father had served. He wants to uncover the truth about his father and, if possible, restore his good name. At first he’s distrusted by his legionaries. They know of his father’s supposed disgrace. He quickly proves himself in battle, however, leading his men shrewdly and bravely to repulse a barbarian night assault. (“Damn the dark,” he growls moments before the attack, a sentiment that must have been universally shared by men asked to hold bastions against barbarous gloom.) Sustaining serious wounds, he’s subsequently recognized for his conspicuous valor and promptly relieved of his duties. This is where the story really begins.

Once Marcus recovers, he ventures north to learn what he can about his father’s fate. He’s also determined to recover his father’s standard, a talismanic golden eagle. It’s reported to have been seen among the northern tribesmen triumphantly displayed as a rebuke to all Romans. To assist him on this mission, Marcus takes Esca, a young Briton of the Brigante tribe whom he’s rescued from death in a local gladiatorial arena. He reasons that Esca knows the northern terrain and the languages of its resident tribes and will therefore be a valuable aide. There’s just one problem: Esca lost his parents to the Roman conquerors and, understandably, hasn’t much fondness for them. The question is, will he stand by Marcus or cut his throat?

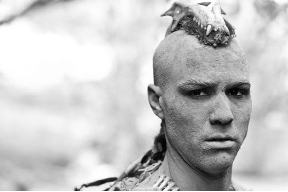

The story proceeds to dramatize the dangers the two men experience after they pass through Hadrian’s Wall. Despite his loss, Esca feels himself bound to Marcus by a debt of honor. For his part, Marcus begins to appreciate Esca’s grievances. Victims of each other’s people, they must struggle to find an honorable response to circumstance. Whether they will fail or succeed in their respective missions makes up the burden of the narrative as they travel through the alternately beautiful and forbidding highlands, tracked by the northern wild men, of whom the blue painted Seal people of the Pict tribe are the most implacable and terrifying.

The tale reminded me of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, especially the passage in which his favorite narrator Marlow sets out to explain some of the unforeseen—or, perhaps, conveniently ignored—consequences of European colonialism in the Congo. Marlow begins by reminding his listeners that England, too, “has been one of the dark places of the earth.” He elaborates by describing what it must have been like for the Roman invaders tasked with bringing to heel the Britons who were then as savage as many an African tribesman was in 1890. His listeners, all indirect beneficiaries of England’s imperial enterprises, scoff at what they take to be an absurd parallel. Undeterred, Marlow insists on the comparison. Imperialism has always gone on, he asserts, adding that it’s usually not much more than a squeeze on peoples who lack the means to put up a successful resistance. This, he suggests, has been a matter of course down to their own time. What really interests him, however, is not the injustice as such, but how such conquests affect the conquerors. Having engaged in imperialism himself as a steamboat captain on the Congo River in 1890, Conrad knew something of these effects. They were far from charming. And yet Marlow doesn’t wholly condemn the practice. “The conquest of the earth,” he explains,

which mostly means the taking it away from those who have a different complexion or slightly flatter noses than ourselves, is not a pretty thing when you look into it too much. What redeems it is the idea only. An idea at the back of it; not a sentimental pretence but an idea; and an unselfish belief in the idea—something you can set up, and bow down before, and offer a sacrifice to. . . .

He breaks off mid-sentence and then goes on to tell of his experiences in the Belgian Congo. He never explicitly returns to explain exactly what this redeeming idea might be. It’s nevertheless clear that Conrad’s Marlow meant something beyond accumulating wealth and power by conquest. He seems to have had in mind the by-products of imperialism. As conquerors the Romans were often extravagantly cruel, but they instituted administrative order wherever they went and often established the rule of law. Against the whimsical and frequently brutal governance of tribes, they brought a degree of rational politics by means of which the subjugated could participate in governing themselves, assuming positions of leadership and, when necessary, appealing for their rights. It was a system that the British emulated in their own colonial enterprises. Conrad had grown up in Poland under Russian domination and knew well what it meant to be oppressed by callous foreigners. His parents went to early graves courtesy of the Russians, leaving him an orphan at ten. Yet he defended Roman and English colonialism up to a point because both seemed to him relatively enlightened. They brought order where little had existed before.

This was Sutcliff’s position also, and Macdonald has adhered to it in his film. He has refused to do penance at today’s anti-imperial, anticolonial altars, which demand we scourge ourselves in reparation for what our forefathers or, in most instances, foremasters did. From Esca, Marcus learns a good deal about what his empire has inflicted on the people it has subjugated, but he doesn’t writhe in guilty torment over it. While he comes to respect Esca and stands ready to ameliorate his suffering, he clearly accepts conquest as history’s inescapable reality. He’s not ready to picket the senate in Rome to enfranchise the swarming savages.

Macdonald’s film is faithful to its source within the limits imposed by commercial film’s two-hour time frame. He’s recreated the look and ambience of the Roman frontier admirably, and his Picts are as gruesomely fierce as one would suppose. The battles are convincingly staged in long shots, the Romans’ disciplined ranks deploying their shields as a nearly impenetrable barrier as they march into their raving, flailing enemies. It’s in the close-ups that the film falters. Macdonald seems to have economized, relying on inexpensive flash editing to give the illusion of violent, chaotic activity without bothering to film expensive tight shots that might have allowed the audience to follow who was prevailing at any given moment in a battle. On the other hand, he’s commendably obscured the grislier moments. There are a couple of suggested decapitations and the slitting of a boy’s throat, which occur just outside the frame. I suspect Macdonald’s purpose was to dramatize second-century barbarism but do it in a way that would not upset younger members of his audience. This is, after all, a boy’s tale.

If somewhat uninspired, the acting is generally serviceable. As Marcus, Channing Tatum is not just glum, which I suppose a young man in his circumstances would be, but unvaryingly glum. This is too much of a muchness. It’s hardly likely he would always be so. Sutcliff’s Marcus certainly isn’t. As Esca, Jamie Bell plays a man of divided loyalties, and he registers ambivalence, anger, and torment quite effectively. The old pro Donald Sutherland is on hand to play Marcus’ wise uncle and dramatic foil. A retired warrior who has made his peace with a cruel and violent world, he stands in pleasant contrast to the tormented young man he graciously advises.

While not a great film, The Eagle is worth seeing, if only for its recreation of Roman battle strategies and its Scottish panoramas.

Leave a Reply