Risen

Produced and distributed by Sony Pictures

Directed by Kevin Reynolds

Screenplay by Kevin Reynolds and Paul Aiello

10 Cloverfield Lane

Produced and distributed by Paramount Pictures and Bad Robot

Directed by Dan Trachtenberg

Screenplay by Josh Campbell, Matthew Stuecken, and Damien Chazelle

You could hardly choose a more unvarnished title for a retelling of the Resurrection than Risen. This film’s one-word past participle is declarative to the point of insolence. It’s a scandal to our intelligence. Yes, risen was and is Christ’s proclamation to the world with neither equivocation nor apology. Leaving the theater, I recalled Flannery O’Connor’s remark at a dinner she attended at Mary McCarthy’s house. Discussing her Catholic girlhood, Miss McCarthy said she had come to regard the Eucharist as a symbol, and “a pretty good one” at that.

The feisty Georgian couldn’t contain herself. “If it’s a symbol,” O’Connor responded, “to hell with it.”

In the same vein, director Kevin Reynolds has made a film that uncompromisingly sets forth the case for the historical Jesus—or Yeshua, as he’s addressed in the film. He walks the audience along the fault line between reason and faith. The first half of the film is something like a detective story in which we follow a Roman tribune named Clavius as he methodically searches for Christ’s body, which has gone missing from its tomb. The second half focuses on the tribune’s dawning awareness of the supernatural implications of the palpably risen Christ he finally encounters living among the rabbi’s disciples.

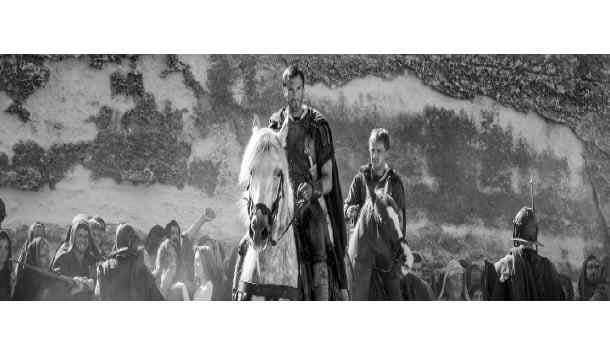

The film opens with a few brief scenes in which Clavius (Joseph Fiennes) leads Roman troops who are putting down an uprising of Zealots. Immediately after Clavius returns to his barracks, Pilate (Peter Firth), the prefect of Judea, orders him to oversee the final grim stage of Jesus’ crucifixion, and then to make sure the body is buried and stays buried. There had been talk that Jesus would rise and become the longed-for messiah. That won’t do, especially with the emperor Tiberius scheduled to visit Jerusalem. Pilate can’t risk an uprising of fanatics. What’s more, the Jewish judicial body, the Sanhedrin, is insistent on the matter. Pilate doesn’t want problems with them, either. He tells Clavius to grant the troublemaker a small mercy by breaking his legs and thus shortening the victim’s agony. Left unsaid because well known to first-century officers, dying by crucifixion comes by way of slow suffocation. The victim rendered unable to move his legs can’t properly breathe.

Clavius accepts his assignment glumly. After all, crucifixions are loathsome affairs.

As played by Fiennes, Clavius is a tough, practical man whose primary goal is to live long enough to retire from the army, marry, have some children, and be at peace. Upon arriving at Calvary, he finds three men tied and nailed to crosses as they slowly, painfully die. He orders their legs broken, but seeing Jesus is likely dead already and wincing at the probable reaction of the mourners, stops short of having it done to him also. Instead, he has one of the soldiers stab a spear under his ribs. As this is done, Reynolds shows in close-up the flesh give under the initial probe of the spear. Unlike Mel Gibson in The Passion of the Christ, Reynolds decided not to drench his audience with blood and gore. Here and elsewhere his film displays admirable restraint. This is a first-century Jew unfairly being put to death to keep the natives quiet, lest they raise a ruckus and embarrass both Pilate and imperial Rome. The Sanhedrin doesn’t want to be embarrassed, either. Its members fear Christ’s followers will try to fulfill his own prophecy of rising from the dead. Clavius intends to satisfy both parties, no more, no less. After having rolled a stone against the mouth of the tomb and sealed it with imperial wax imprints, he leaves it in the care of two guards. These men, however, are given more to drink than to duty, and soon fall asleep. And of course, at dawn on the third day, the stone is found rolled away.

From here the film’s narrative assumes the character of a police procedural. Clavius and his officer-partner, Lucius (Tom Felton), begin to search for the missing body, going about their task as methodically as thoughtful detectives unraveling a mystery. They begin by questioning Christ’s known associates.

When Clavius finds Mary Magdalene, he asks where Jesus is; she replies simply and movingly, “He’s here, he’s everywhere.”

Having already detected something unusual in Jesus on the cross, Clavius recognizes that this woman is different also. He senses it in her tenor and courage in responding to him. When his second-in-command offers to torture her for the truth, he dismisses such a tactic out of hand.

When, after more detective work, Clavius deduces that the apostles are in the upper room of an inn, he bursts through the door to confront them. The scene is nicely shot. At first confused by the 11 men tightly gathered in a small space, he only glimpses the 12th—who is, of course, Jesus. The camera catches the Lord’s face here and there between the bodies of the others. Then Jesus smiles at Clavius almost mischievously, as if to say, “Yes, here I am, your quarry and your friend.” In an instant, Clavius recognizes Jesus as the crucified man he saw a few weeks before and sinks to the floor in exhaustion and amazement. Until this moment, Fiennes’s face has been closed in anger and frustration, but now it opens with something like wonder. I can’t say how the actor did it. All I know is that he did. And with the change in his face comes the point at which reason gives way to the first inklings of faith. Some commentators have praised the film for its dramatization of the detective work and faulted it for shifting into the miraculous. This criticism misses the mark entirely. Reynolds has deliberately confronted us with the point at which reason must give way to faith or embrace nihilism, and he’s done so superbly.

Cliff Curtis, who plays Yeshua, comes from New Zealand and is of Maori descent. His coloring and features have allowed him to pass as a Middle Easterner in several films, most notably in Three Kings. His acting is never showy. He prefers understatement to histrionics. As such he’s just right for his role as the Christ who comes as an ordinary man among simple souls who find him irresistibly compelling. This ordinary man is made extraordinary by the evident strength of his conviction in his divine mission and his gentleness in dealing with both friends and enemies. What I liked most of all was Curtis’s smile and the way he laughs quietly with the disciples. It’s as if they’re amused that God’s grace chose them and can’t quite get over it. Tentatively at first, and then with increasing certainty, Clavius joins them, smiling in astonishment at his own change of heart.

What’s truly amazing is the simplicity with which this is played. It’s as if Dostoyevsky’s Christ openly told the Grand Inquisitor that miracles are not the point. Or, rather, seen rightly, everything is a miracle. Who, upon reflection, could doubt the truth of such a message? It’s amazing how often we do. Where are our eyes, our ears, our senses of smell, taste, and touch? The miracle is always around us. Of course, Jesus, God incarnate, fully recognizes this and intends to share it with us if we choose to let him.

See Risen. It’s a rare, lovely, and utterly convincing film about the most important event in history.

10 Cloverfield Lane doesn’t need to be seen unless you’re in the mood for some shrewdly executed thrills achieved on a scant budget. If you are, by all means go to your local theater. You’ll be royally entertained. It delivers some real surprises, including a whammy of an ending that you won’t see coming, not unless you cheat yourself by talking to some friends who have already seen it.

There’s no grand theme. True, some have read the film as a feminist protest against male domination. But, given the narrative’s events, this seems an unwarranted stretch into ideology. The film opens with a silent passage. Michelle (the beautiful Mary Elizabeth Winstead), a young woman, wordlessly gathers her belongings in preparation for leaving her fiancé, whom we never see nor learn anything about other than that he had an argument with her for some unspecified reason. Soon she’s driving on a deserted highway to an unknown destination. Before you can ask what this is all about, a truck sideswipes her, and she awakens in what seems to be a cinder-block basement chained to a metal-framed bed with an IV in her arm. At this point, I began to think I was at the wrong theater. This sequence has something of the character of one of the installments of the hideous Saw franchise, of which I’ve watched a couple of scenes before walking out. Practicing film criticism shouldn’t require one to be thoroughly disgusted.

When John Goodman entered the room, I was reassured. I couldn’t believe an actor as accomplished as Goodman would stoop to such dreck. Goodman is Howard, and he explains that he’s rescued Michelle both from her accident and from an alien attack that has left the upper world uninhabitable. They’re in his underground survival bunker, he claims, and it may take one to three years before they can leave safely. Along for the stay is Emmett (John Gallagher, Jr.), the young man who helped Howard build the bunker and make it impenetrable to outsiders.

This is the situation Michelle faces. It’s certainly a doubtful one, except that, as time passes, events keep making it seem, let’s say, not unreasonable. But then again, other events seem to undercut its plausibility. To say more would be to detract from the film’s spell, so I’ll simply write that this is an impressive thriller. It boasts almost no violence and minimal gore. First-time director Dan Trachtenberg works with cinematic ingenuity to keep us at once riveted and off balance. He shoots most of his scenes in claustrophobic close-up, often with his camera position near floor level. It’s an unnerving visual strategy that advances his film’s unfathomable portent.

Leave a Reply