Does America exist anymore, or is the nation only a fantasy concocted out of old Frank Capra movies, civics classes, and pamphlets from the Department of Education? The weight of the evidence suggests the latter. Twenty years ago—ancient history by the standards of the press—a considerable number of young men who refused to fight in Vietnam were willing to riot in the streets for the rights of Indians, Southeast Asians, and various American minorities; leaders of the American Indian Movement have from time to time claimed the rights of sovereignty for the tribal fragments living on reservations; Japanese Americans, while asserting all the rights of citizenship, sue the people of the United States for the mild, although not always justified, safety measures taken by Earl Warren and President Roosevelt in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor; and for several decades illegal aliens have been swarming across our southern border, finding refuge with dishonest fruit-growers and religious communities willing to sacrifice the public good to the inner light of personal revelation; their children, according to the courts, must be educated at the local taxpayers’ expense because an American education is a basic human right for all the world’s population. The rumors about American education must not have made their way down to Mexico.

National identity and the privileges of citizenship have been in conflict since the war for American independence. Were loyalists traitors to America or faithful subjects of the King? If they stayed long enough to be judged traitors, did they have the rights of citizens after the war? (The answer is yes.) Were Indians American citizens or were their tribes subject nations? (No and maybe.) The biggest question turned, of course, on the status of blacks—both free and slave.

In a country where slavery was legal and embedded in the Constitution and where only white immigrants could be naturalized as citizens, the status of free blacks was a puzzle. The pieces were not really sorted out until fairly late, when the issue became a matter of sectional loyalty. Inevitably most Southerners (with the support of a good many Northern men) came to insist that slave or free, blacks were not and could not be citizens. The Yankee political leadership, just as inevitably, took the opposite view.

The controversy came to a head in the famous case of Dred Scott. In the 1830’s Scott’s owner, an army doctor, had taken his slave to the free soil of Illinois and the Wisconsin territory. The doctor returned to Missouri with his servant, and after his death, the widow married an abolitionist who wished to use the matter as a test case in the courts. In 1852 the Missouri Supreme Court ruled that while Scott could have been freed in the four years he spent in the North, his servile status was reconfirmed upon returning to Missouri.

The issue, however, was potentially larger than the simple question of Dred Scott’s legal status, and when in 1856 the Supreme Court ruled against Scott, Chief Justice Roger Taney decided to take up the whole question of citizenship. Writing for the majority, Taney argued that blacks did not have the right even to bring suit in federal courts, since they could not be citizens. Citizenship, he argued, was restricted to the people of the United States at the time the Constitution was ratified, to their descendants, and to those white foreigners who had been adopted into the commonwealth. No free state could make blacks citizens, because that right belonged to Congress acting for the nation as a whole. By denying them such basic rights as voting, jury service, and office holding. Northern states made it plain that they did not actually include free blacks in their citizen bodies.

In his dissent Justice Benjamin Curtis pointed out that the constitutions of several states had given citizenship to all free-born natives, regardless of color. It was up to the states, he argued, to determine who their citizens were, and state citizens were automatically national citizens. What a strange situation, in which Taney, the Jacksonian Democrat, supports the national government against the states rights claims of abolitionists. The technical and legal questions inspired by the decision will never be solved, but the judgment against Scott was the only possible decision for the court to hand down: it has only been in this century that courts have regularly usurped the power to make laws. The Chief Justice himself upheld the right of Congress to change the law—and nothing so marks the dishonesty of American historiography as the vilification that Taney has endured posthumously.

In the great national debate, the strict-constructionist argument was simple: Citizens were citizens; there could be no degrees. While women and children exercised their rights primarily through the male head of the family, this was an arrangement universal in the human species. Even property qualifications were not a genuine civil disability, since anyone could, at least theoretically, work to acquire the necessary wealth. The case of free blacks in the North was, however, entirely different. No matter what the merits of the individual might be, no matter what his service to his country (Lincoln was dubious about the political rights even of black Union veterans), he could never take his place as a political equal.

Some politicians fell back on the convenient notion that the word citizen in America meant no more than subject in the common law tradition. A subject is simply someone born in allegiance to the crown or, in our case, to the government of the United States. In return for his allegiance the subject was protected in his property and guaranteed the rights of due process. Some citizen-subjects could vote, hold office, serve on juries. Others could not. Progressive thinkers then and now saw nothing wrong in having a servile, dependent class of second-class “citizens.”

The merits of such an argument and of such political distinctions are strictly historical. The American notion of citizenship did in part grow out of English law on subjectship, and recent scholars have quite correctly related our own debates to the differing traditions of English law and political philosophy. In the older common law tradition, birthright conferred perpetual subjectship. In the simplest case, anyone born on English soil was an English subject, and the English periodically reassured themselves that the King’s heirs were really subjects, even if they were born in a foreign country. The newer doctrine of consent was argued by John Locke and even more radically by William Godwin. The accident of birth could not, it was argued, condemn a man to perpetual allegiance. Upon reaching maturity a subject was free to choose his nationality. (By the same token, Locke interpreted the family as a sort of contract for mutual benefit; grown children owed nothing to their parents.) Under the old doctrine, free black natives were obviously subjects, but by the terms of the new liberal argument, citizenship was based on tacit agreements between the state and its citizens, and the grounds for such a contract between the United States and free blacks proved hard to establish. Ironically, it proved easier to deny black citizenship on Locke’s liberal grounds than under the older common law.

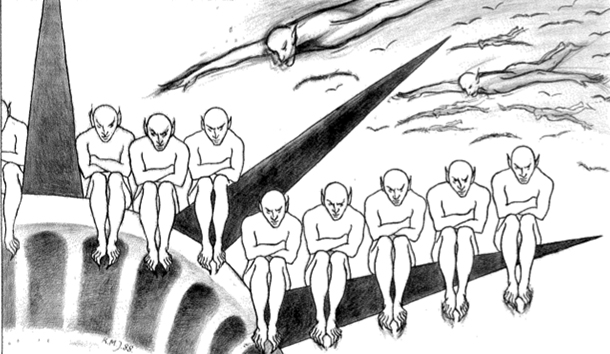

But in addition to the twin English traditions of subjectship, there is the ancient notion of citizenship that was partially revived by the English republicans. Citizens were not, in a Creek polis, passive recipients of equal rights to legal due process; they were active participants in the life of the commonwealth. They served on juries, met periodically in the assembly, and—in the fullest understanding of the term—they could and did hold public offices. Citizenship was almost entirely based on the ius sanguinis, the right of descent, since the polis was essentially an extended family and not, as in the case of a modern nation, a marketplace of rights and obligations. At Sparta even birth was not enough: boys had to go through the rigors of Spartan education if they wished to join the homoioi (equals).

Perhaps because of their affection for the classics. Southerners were prominent among the many Americans who embraced this active conception of citizenship. If they were wrong about a great many other things, they were at least passionate in their devotion to country. It is no accident that rural people in general, and Southerners in particular, have given America so many of her greatest soldiers. They believed, again quite passionately, that no one can be a good citizen if he shirks his military obligation, avoids jury duty, or shrinks from the sordid reality of public service.

The Civil War and the 14th Amendment settled permanently the question of slavery; it did not solve the problem of citizenship. On the one hand, blacks continued to suffer under a variety of legal disabilities that made a mockery of the 14th Amendment’s solemn declaration that “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside.” On the other hand, the Amendment restored the old and largely irrelevant doctrines of the common law. The American way of life, that is, the product of the peculiar virtues and habits of the American people, includes a generous—some would say too generous—provision for the welfare of the unfortunate. In ancient Athens, the existence of welfare benefits compelled the Athenians to put rigid restrictions on citizenship. In America, the opposite is the case. Illegal immigrants are given amnesty, and legal aliens are free to avail themselves of a smorgasbord of rights and benefits with no strings attached. Under the circumstances, it is hard to see what citizenship means or what advantages citizens possess.

The rediscovery of citizenship is among the most pressing problems faced by the American nation. One hundred years ago enlightened and progressive political leaders panicked at the thought of so many immigrants from Ireland and from southern and eastern Europe. They not only began to tighten restrictions on immigration—probably a sensible move—but they also decided to use the power of government in their effort to Americanize the newcomers. Many of the most objectionable features of our educational and welfare systems were designed as measures to convert or control the Catholics. They only succeeded in temporarily alienating them from the mainstream. In the end, Irish and Italian Catholics became just as good Americans as the Swedish Protestants who attended public schools, but we are still saddled with the coercive mechanisms of Americanization.

In their effort to define America as an idea that can be taught, progressive educators and journalists turned to the slogans of the French Revolution for their inspiration. We can hardly blame the immigrant children for growing up to believe that the United States was created by the 14th Amendment, or that equality was the most basic principle of the Constitution. Unfortunately, many of these Americanized newcomers grew up to be journalists and educators themselves, and ever since the First World War we have had to hear the cliches of Americanization parroted back to us by the second- and third-generation immigrants who domineer over the nation’s conscience from their citadels in the northeast.

The worst mistake we could make at this point in our history—and there are those in the U.S. Department of Education who are eager to make it—would be to rely on education, once again, as the remedy for our immigration problem. European Catholics are one thing, Buddhists from Asia and Caribbean devotees of Santeria and voodoo quite another. Increasingly, we are told that it is not only in our interest, it is also positively our duty to open the country to anyone who wishes to come, whatever his motives and whatever his prospects. The open border is, in fact, more or less the present reality. In such circumstances, we have only two choices: either redefine the United States as an imperial state whose subjects are held together only by ties of law and bureaucracy—which is what our ruling class seems to have in mind—or else rethink the meaning of national citizenship.

In their recent book, Citizenship Without Consent, Yale scholars Peter Schuck and Roger Smith draw attention to the major flaw in our liberal understanding of citizenship. If nationality is largely a matter of consent, a contract between citizens and the nation, then it is within the power of either party to withhold their consent. While urging a more generous immigration policy, Schuck and Smith take the necessary—and very risky—step of arguing against ius soli citizenship: How can the American people or the government be said to “consent,” when illegal aliens or casual travelers bear children upon American soil?

This is an important step in the right direction; however, it is not necessary to restrict our conception of citizenship to the bloodless abstractions of John Locke and international law. As an alternative, we as a nation might reconsider our own old-fashioned and robust citizenship as one of the answers to the growing problem of ethnic strife in America. No matter how generous we are in our immigration policies, Schuck and Smith are right: the notion that anyone accidentally born in U.S. territory automatically becomes a citizen—as the 14th Amendment seems to guarantee—has to be abandoned. It derives from the all but irrelevant common law doctrine of ius soli. We cannot as a nation continue to tolerate the large number of illegal aliens who come to America for the sole purpose of producing citizens or finding jobs.

As a corollary, we would need to redefine the duties—as opposed to the rights—of citizens. Any minimum definition would have to include: the obligation to vote, to serve in something like the National Guard, and to pay taxes. Refusal to perform such duties or the willingness to live on the nation’s bounty as a welfare dependent would result in an automatic (although not necessarily permanent) change of status from citizen to subject. As a subject, the shirker would enjoy equal protection under the laws but could not vote, hold office, or serve on juries. Rich and poor would be affected alike, since the poor are more likely to go on welfare, while the rich are more likely to evade military service. (Remember Vietnam?) Combat duty should wipe the slate clean.

Why do I think we will never consider something like the above? Think about it. Minority spokesmen would lose their clout, the liberal rich could not continue to send poor blacks out to die for their favorite charities—like the suicidal Lebanese or social justice (democratic or Marxist) in Central America. We could begin to deport all noncitizens on welfare. Rioting Iranians would be shown the door within 24 hours, like guests that have overstayed their welcome. Real democracy, the strong democracy advocated by leftists like Benjamin Barber, might then be allowed to function, and the movers and shakers of both parties would dry up and blow away like flyspecks on the wall. Democracy? Good lord, anything but that!

Leave a Reply