“I grow old learning many things,” said Simonides, a poet X well known for his wisdom and for his longevity: He lived to be almost 90. Although, as my old teacher Douglas Young pointed out, Simonides’ statement might be interpreted to mean “too much education makes one prematurely old,” the point is clear enough and as true today as it was 2,400 years ago when the Greek poet went from town to town, composing odes and epitaphs for his fellow aristocrats; A wise man never ceases to learn new things.

Simonides’ reputation for wisdom was so great that Plato took him on in the Protagoras and tried to discredit—unsuccessfully, in my opinion—the poet’s definition of virtue as a reflection of a good conscience and character. Aristotle, who did so much to restore character (as opposed to merely rational understanding) to the center of ethics, would also have approved of Simonides’ commitment to learning. In fact, he opened his Metaphysics with the statement that man is born with the desire to find things out. To give up learning, then, at any age, is to cease to be fully human.

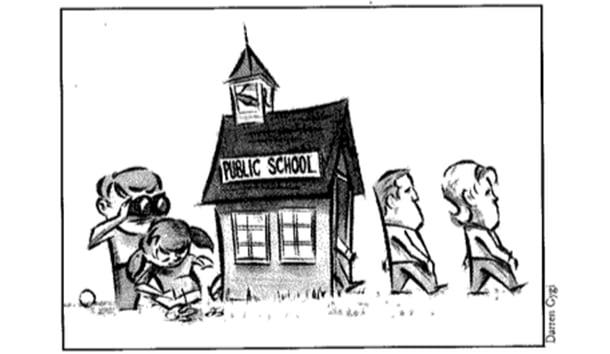

What, after all, distinguishes the human race from other predatory mammals, if not his curiosity? All mammals, to be sure, go through a process of education, as they are taught to hunt or forage and obey the rules of the pack or pride. For tigers and wolves, the process lasts a few years (rodents have even a shorter time to find the wisdom that will enable them to survive), but the higher apes continue to learn up to perhaps the end of junior high school age, which beats the average American who attends public schools.

In the wild, many human beings seem to reach maturity (that is, the point at which they stop learning) by the age of 21, and until recently the government recognized the fact by making 21 the age at which boys and girls were considered obedient enough to vote and sufficiently dull-witted to want to drink themselves unconscious in a public place.

Humankind is unusual in prolonging all the stages of development (except for in utero development: Our oversized heads require premature delivery), and the higher types of humanity—poets, aristocrats, warriors, and composers—are noted for preserving a certain juvenile openness to the end of their careers, if not of their lives. Mozart died young, but there is no reason that he would ever have grown up, any more than “Papa Haydn” or Sophocles or G.K. Chesterton really grew up.

Animal trainers and primatologists know that every species has its limits. You can’t teach an old dog new tricks, and a gorilla that has learned sign language in its youth will, upon reaching maturity, adamantly refuse to play along, even if he can get a treat every time he flashes the correct sign. In training dogs and horses, care must be taken not to destroy the animal’s spirit. Vachel Lindsay’s “broncho that would not be broken” died rather than allow itself to be turned into a machine, and the mad poet apostrophizes the colt in the glory of his freedom:

As you dodged your pursuers, looking askance

With Greek-footed figures, and Parthenon paces,

O broncho that would not be broken of dancing.

America is full of high-spirited boys who will join gangs or follow the Grateful Dead from town to town before they will permit their souls to be destroyed in a government school.

I can almost hear the latter-day Gradgrinds objecting: “Boys must be disciplined and prepared for careers in the 21st century.” It is true. Every society, whether of rats or Rotarians, has its rules and its system of discipline, and part of everyone’s education must be the trial-by-ordeal in which we learn the penalties for robbing the neighbors or chewing with the mouth open, and a nation whose business is business must enforce the code of the Rotarian, willy-nilly, upon the children of Zenith and, more recently, of Yoknapatawpha.

It is no accident that American education first emulated the techniques of the factory and then passed them back again, suitably streamlined, to the efficiency experts. The inventor of “Taylorism” confessed that he had been inspired by the routinized assembly-line instruction he had observed in Massachusetts schools. Leftist and libertarian historians—Joel Spring (The Sorting Machine) and Michael Katz (The Irony of Early School Reform)—have traced the symbiosis of school and factory which, in more recent times, has spawned such mind-deforming programs as “School to Work” and the thousand-and-one proposals from national and local groups of illiterate businessmen who think they know how to reform education. If the CEO’s of Fortune 500 companies wanted to do something about education, it has always seemed to me, they might begin with themselves.

But if every society needs its workers and team players, its sports fans and robots, it also needs a class of leaders, of warriors and dreamers who will fight for something grander than the GI Bill and sing the songs that make life seem, if only for the moment, worth living. We all know, even the CEO’s, that the United States has failed to train our robots and worker-ants in the habits of diligence, punctuality, and thrift; and some of us are even aware that our math instruction is so poor that we have to import Asian students to fill the places in our engineering schools (something like half of our engineering graduates are foreign-born).

I would like to say I was alarmed by these developments, but I am not, because this country has already failed in a far more important—indeed, the primary—task of education, which is to form the mind and character of an intellectual, moral, and social aristocracy that is the only exercise for all the dirty business that a nation does. Other societies have fouled the water and slaughtered the innocent at the same time they were producing the younger Cato or Walter Scott or George Patton. Yes, America did once produce men who were both warriors and dreamers, men of action (like Robert E. Lee and Douglas MacArthur) who lived by a higher code than can be contained in a Dale Carnegie handbook or an inspirational lecture by Tom Peters. What the United States grinds out year after year, however, are post-human androids, the likes of Bill Gates and Wesley Clark and George W. Bush.

If Gaetano Mosca was right—that every nation’s character is defined by its ruling elite—then U.S.A., Inc., must be set several notches below the Assyrians, who were, at least, colorful in their butcheries and distinctive in their art. Next time you visit Chicago, go to the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago and see what is left of Nineveh and Tyre. (The collection, by the way, owes much to the exertions of by far the greatest man ever to grow up in Rockford, J.H. Breasted, whose name is forgotten in his hometown, which, like most hometowns, has tried to eliminate its historical memory.)

As uncongenial as the worlds of Hammurabi and Senacherib are to an American, the freshness and vitality of their art (much of it creatively borrowed from the Sumerians) is disconcerting to people dulled and blunted by the endless line of products pitched at weary K-Mart shoppers. The Assyrians were as nasty and violent as Madeleine Albright, but they were no hypocrites: They exulted in brutality and boasted of it in their monuments. It is not our victims’ blood that should be gagging Americans but the pious lies that are used to cover them up. We swallow them, though, and for all their bitterness, we keep down the poisons that are killing us. Better to be an Assyrian.

I have taken my children to the Oriental Institute twice, once when they were being taught (not “schooled,” if you please) at home and once when they had some private school education under their belts. On the first visit they were, despite their silliness and immaturity, still open to experience, but by the second they were exhibiting the signs of the bored, resentful products of a religious school doing its best to ape the public schools of 1962.

Their parochial high school, while it succeeded in teaching them to sit still and work out algebra problems (which we never could do at home), has also poured cold water over the glowing embers of their youthful curiosity. Their religion classes taught them the faith of Voltaire and Martin Luther King, Jr.; history and literature amounted to a series of documents in the progressive struggle against European Christian patriarchy; and their manners and dialect were reduced to the patois and gestures of delivery boys at the bottom end of Rockford’s famous “Pizza Connection.”

Back in the 1960’s, the Yippies used to say, “Your children belong to us.” They were right, in a sense, but my kids don’t belong to Grace Slick or Tom Hayden, but Mr. Hayden’s children (if he had them) and mine both belong to McDonald’s and Disney and Buffy the Vampire Slayer, whether they have ever eaten a cheeseburger or turned on the television.

Buffy’s fans, by the way, were desolate this summer, when the network, in the wake of the Columbine shootings, decided to postpone the final episode, in which the fearless vampire-killers kill the principal, who has taken the form of a 20-foot snake demon. Demons are apparently still safe in public schools; it is only students and teachers who have to worry about getting shot.

My primary fear, however, is not for the dangers our children’s bodies are exposed to in schools but for the sterilization of their minds—

Too much the baked and labeled dough

Divided by accepted platitudes.

Across the stacked partitions of the day . . .

—that Hart Crane observed two generations ago. Better to plunge them again into the chaos of a household where Simonides is no stranger, Simonides who is still learning more in his grave than their fellow students will ever learn in their school.

At this point in the argument, Dr. Gradgrind, Ed.D., plays his trump card: social necessity and the common good. “If von don’t send }our kids to school, they will never learn to get along with other people.” In other words, the real purpose of school is to socialize the little barbarians.

There might be some truth in this. With no authority more objective than an adoring mother to pass judgments on their performance, the typical product of homeschooling may be an unbearable monster, even more spoiled and self-centered than his public-school counterparts. The problem lies not so much with the actual fact of studying at home as with the character of homeschooling parents, who are just as ignorant, just as self-indulgent, and just as muddleheaded as anyone else born since 1940. They cannot discipline their children (they can’t even train their dogs) because they refuse to discipline themselves.

Many homeschooling parents are aware of the problem and send their children to music classes and tutors or club together into a cooperative school (where they can spoil each other’s children). But granting the worst case that my children’s grandmother can make against homeschooling, we only need to point to the public schools of America, where teachers are held hostage by violent students, where drugs are sold and used openly, where bad manners and perversity are deliberately inculcated in the classrooms, and where “counselors”—the bane of modern life—try to drive out every vestige of decency and modesty the children might have brought from home.

Home schools do not fail because they do not teach their children more and better things than they could learn in public schools; they fail, ultimately, because there is no common culture to sustain them. It is all very well for a literary eccentric to bring up a fourth generation of literary eccentrics—that is all I ever aspired to; but most mothers do not want their babies to grow up to be cowboys or Indians or specialists in Greek lyric meter or translators of Pasternak. They want their sons to be doctors or lawyers or real-estate magnates, men who will settle down and raise a family in some town where they can put down roots for 20 years, at least until their kids are in college, when they can move to Arizona or Costa Rica.

Some parents also want their children to grow up to be real men and real women, not simply employees (or entrepreneurs) and taxpayers. This is the only purpose of education—to teach us what to do with the half of our lifetime we do not spend on sleeping and working—and such an education inevitably entails a common culture based on books. Each family could make up its own curriculum, of course, if it lived in the wilderness and had no historical memory to preserve. We have come along too late in the world for that. To make sense of our own lives, we have to know who our people are, or were, and learn to think as they thought, even if we someday come to reject their conclusions.

There are no secrets to what constitutes a “good education” for an American: It is the Greek and Latin classics (preferably in the original), the Renaissance literatures of France and Italy, the best books written in Britain as well as our own provincial contributions to English literature.

There is a revival, of sorts, of the classics, not in the Ph.D. programs of major universities but in alternative colleges such as St. Thomas More in Ft. Worth. Calvinist academies like Douglas Wilson’s Logos School in Moscow, Idaho, and in some of the sunnier spots of the homeschool movement. At this point, these projects in classical renewal are so many straws in the wind, not enough, perhaps, to make a dozen bricks in Goshen. The Hebrews, we should remember, were bitter because an evil and repressive government that killed their children was denying them the straw they needed for making bricks. They had to find their own straw, and we have to find our own bits of learning to make the bricks and mortar of our selves. Our dream, ultimately, is their dream, that we and our children will someday be freed from bondage to worship God and save our inheritance.

Leave a Reply