In troubled times, we look for something to hold on to as the dangerous currents are sweeping us downstream to destruction. Some will have the clear sight (or unthinking prejudice) to grab on to some rooted feature of the landscape—the limb of an oak tree, the steeple of a church, the arm of a brother; while others make the mistake of reaching for something more recent and showy—an ornamental bush, a golden arch, or the hand of a political ally. For stupid people, which means most of us, it makes all the difference whether a man in distress turns to the Gospels or to a grief counselor.

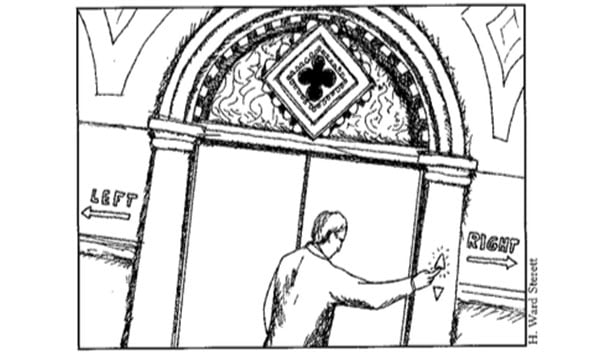

Even in the smog of politics, we thrash the air, searching for something solid and enduring, but the great mistake—in politics, as in most of life—is to mistake the familiar for the permanent. The world of the 1950’s is gone for good, and with it the postwar alignment of states and parties. Those who take their stand on the platform of the Republican Party will soon be looking through its holes into the great vortex that is sucking them in, and those who try to keep in step with some imagined “conservative” movement (in what direction should conservatives want to move, except backward?) will ride their slow freight all the way off the cliff.

I touched upon these matters almost a year ago when I gave a speech in an ex-convent across the Adda River from the village where Lucia Mondella and Renzo Tramaglino were supposed to get married some 360 years ago. Those dim-witted Lombard lovers had a grasp of the permanent: love, faith, hard work, courage. Then, as now, there were unscrupulous oppressors as well as cowardly and faithless priests and nuns, but even the cowards knew the truth, not only in the 17th century, when these fictional characters were undergoing the perils of thwarted love, famine, plague, and war, but also in the 19th century, when Alessandro Manzoni was writing I Promessi Sposi.

And there I was, not five miles from Manzoni’s home, 150 years later, lecturing an Italian audience on the themes of empire and oppression, not of the Spanish and Austrian subjugation of Lombardia, but of America in the Philippines and in Kosovo, an argument I had been making, it seemed, all over the world—in London and Paris, in Chicago and Berkeley, in Sydney and Adelaide. “La fine del secolo Americano.”

When I gave my talk in the restored chapel, the one or two ex-Christian Democrats (Italy’s Cold War “conservatives”) were incensed. The moderator of the panel, a former ambassador to the United States, was furious and afterward exploded at me, insisting that all the lies he had heard about Racak and ethnic cleansing were true, that the American government would never be guilty of unprovoked aggression. When I told him that he and his government were as much victims of American lies as the American sheep who bleated in unison with the CNN broadcasts, this calm and benevolent diplomat started screaming, “I suppose the holocaust never happened either,” and he stormed off waving papers in the air as if he were trying to flag down a taxi in the middle of an Italian garden.

Since most Italians are too realistic to be conservative, the talk was a great success. More than a few radicals came up to find out which section of left field I had come from, and they were not at all unhappy to learn that I came from the right. Those labels belonged to the past, they said, and in our subsequent conversation, the young leftists turned out to be more green than red, defenders of community and naive traditions, opposed to the expansion of government coercion in the name of rights.

In America, the smart money is buying puts on the current alignment of left and right, of performing mastodons and domesticated onagers. In Italy, where politics is a matter of jumping from one unresolved crisis to another, they are simultaneously transforming their electoral system and floundering around in a hopeless effort to find competent leaders. The communist government of Massimo D’Alema has been a total flop, and if many Italians once believed that the communists whatever their faults—held out the promise of effective, honest government, they know better now. Their prime minister (who looks like an organ grinder dressed up for a funeral) has done nothing to save the Italian economy, much less the lira, and while a communist might have been expected to stand up to NATO, he caved in and allowed NATO’s murderous airstrikes on Yugoslavia to be carried out from Italian bases, contenting himself with whining.

What is the result? An influx of Kosovo Albanian criminals who are robbing, raping, and murdering their way across central Italy. The Sicilian Mafia was like a pack of wolves, picking off weakened animals and resting when their bellies were full; the Albanians are more like piranhas who never seem to get enough. The Italian ministry of justice, commenting on the rash of robberies and murders, remarked that respect for human life is not part of the Albanian mentality.

Most Americans do not want to know that recent immigrants are far more likely to commit violent crimes than native-born Americans, but Italians must not watch as much television. A recent European poll revealed that Italians were more concerned about immigration than the citizens of any other country. What was their primary concern? Not the loss of jobs or their national identity, but the loss of their lives. In fact, almost half of all Italians believe that their lives and safety are threatened by immigrants.

In the past few years, the only major party to make immigration an issue was the Lega Nord. In recent months, however, Umberto Bossi has made another rapprochement with Silvio Berlusconi, the media/investment magnate who started Forza Italia. The last coalition that joined the Lega with Forza Italia and Berlusconi’s right flank, the post-fascist Alleanza Nazionale, ended in a debacle when Bossi and the Lega voted against their own government. Rossi’s “ribaltone” enabled the “ex”-communists to come to power, and in the intervening years, the Lega has more than implied, on many occasions, that Berlusconi is connected with the Mafia.

In a bold political move, Berlusconi has decided to adopt his once-and-future partner’s position on immigration, and the three parties have proposed fairly radical immigration reform legislation. Despite the technical language and gestures of concession (more aid for refugees, an automatic citizenship plan for immigrants who have been legal residents for ten years), the proposed law would represent a revolution in the Italian post-fascist mindset.

In a country where patriotism is a thoughtcrime, nothing could be more radical than an immigration reform proposal that recognizes Italy’s right to exist and to control its own destiny. Article three, for example, stipulates that, twice a year, the regions of Italy will define the numerical limits and types of employment needs, and on that basis, the country’s openness to immigrants will be determined. Article 11 provides for the expulsion of aliens who enter illegally, exceed the term of their permit, or constitute a threat to public order and safety. That last clause is clearly meant to address the growing problem of Albanian immigrants, who have displaced the Sicilian Mafia, ill much of the peninsula, as the masters of drugs, prostitution, extortion, and violent crime.

The reaction of the Italian press lords has been predictably dishonest, and Berlusconi is being compared with Le Pen, Haider, Hitler, and any other villain that their limited imagination can conceive. On April 3, La Stampa (the Italian Wall Street Journal) led off with a predictable hissy fit: “The immigration proposal is superfluous and in contrast with the center right’s basic values, particularly the free market, unity of the family . . . e cosi via.” Giampaola Pansa of L’Espresso, in his column “Adesso mi arrabio” (“Now I’m mad”), concedes that there may be too many illegal immigrants in Italy, but does not dissent from the official opinion: “È stato detto, giustamente, che è folle, antidemocratica, antieuropea, razzista, simil-Heider, regressivo in senso culturale e storico, inchiodata sul concetto superato di nazione etnica” (“nailed onto the outmoded concept of the ethnic nation”) and so on and so forth—why bother to translate? We know the tune all too well.

Americans sometimes think theirs is the only “nation of immigrants” beset by ethnic conflicts and bound together by the flimsy cords of a national ideology. According to our official propaganda, America is a nation “dedicated to the proposition”; according to their official propaganda, the varied regions and cultures of Italy were unified in the Risorgimento, a glorious uprising that unified Italy and culminated (after a few disgraceful decades in the middle of the 20th century) in a universal nation more or less like the United States.

Italy’s Great Lie is taught in schools, but even a casual visitor can smell the difference between the real Italy of farming villages and small workshops and the massive industrial projects that have polluted the air and water and turned much of Northern Italy into a down-market replica of Cleveland. Even by American standards, Italian “democratic” politicians of the left and right are a pack of strutting clowns who strike attitudes for the television cameras, fill their own pockets, and—at their best—do nothing.

I saw a microcosm of the Italian miracle in early June. I was asked to go to the village of Consonno (about ten miles from Leceo) and to evaluate its possible use as a site for foreign students. I had driven this way before, climbing up the steep hills that rise above the Adda River from Olginate to Garlate to Galbiate toward Colle in Brianza, leaving behind the crowded streets and pestilent motos and finding the ancient farms and pastures where some part of the real Italy is preserved.

The day was hot and humid, but as we rose above the smog, I could forget Hie endless traffic jam that Lombardia has become and the unending verbal battles between the phony right and the phony left. The woods were thick with chestnut trees, and in their shade, the locals could pick the funghi that grew in abundance—porcini, boletus, and others whose names I had not so much as heard.

The shock was Consonno itself. Sometime in the 1960’s, the city fathers of Olginate had decided to construct a model town complete with hotel, disco, and shops. This little commercial community was constructed in the best nightmare Moorish style, complete with a tower that looked something like a minaret designed by Disney.

The place flopped immediately; the shops closed; and the young people who had not gone to the disco came on weekends to trash the place—not that it could have been made worse. Everything had been built of such shoddy construction that, after only 30 years, the sidewalks looked like an earthquake had hit. Only a mile or two away, you could find farm buildings and churches that had lasted for centuries. This tribute to America had not survived the end of the Cold War.

We were taken to Consonno by our old friend Elvio Conti, one of the four founders of the Lega Lombarda. Elvio’s mother had been born there, and her parents were buried in the small cemetery which we could not enter because the city fathers of Olginate had decided—contrary to tradition and probably against the law—to keep it padlocked. Elvio is a sound businessman who believes in the free market, but he wonders why his mother’s village had to be ruined, why the entire area had to be flooded with welfare cases from the South, and why all of Italy has to be transformed into a hybrid of Albania and North Africa whose fitting symbol is the commercial minaret of Consonno.

I tell the story of Consonno to friends at dinner, and Eugenio Corti informs me that Consonno is proverbial for being a village of idiots and retells the story (which exists in many languages) of the villagers who wanted to feed a hungry donkey. When they find some grass growing out of the bell tower, instead of pulling up the grass and taking it to the donkey in the piazza, they put a rope around the donkey’s neck and hoist him to the top of the campanile. Seeing the death rictus on the animal’s face, they exclaim: “See how happy he is to have the grass.” Later, an outsider comments that the dead donkey was the only creature in Consonno that had any sense.

All of Italy is Consonno now, and, confronted with Third World poverty, instead of doing the sensible thing—which is sending the grass to Tunisia or Albania—they are bringing the Tunisians and Albanians to their own campanile. This time, it is not going to be the donkey that perishes, but Italy. Like most people, Italians are hypocrites who like to attack the United States for its “racist immigration policies, but when the time came to ship the Albanians back where they came from several years ago, most Italians breathed a sigh of relief. This bold initiative of the Polo-Lega alliance may be the first step toward the creation of a genuine rightist political coalition in Italy, one that will transcend Berlusconi’s puerile fascination with American consumerism and the German electoral system.

Nearly ten years ago, the alliance of Bossi, Berlusconi, and Fini offered hope to millions of Italians who wanted a decent government and a decentralized constitution. For reasons known only to himself, Umberto Bossi destroyed that coalition. After nearly ten years of Marxist misrule, Bossi seems to know who the enemies are. Let us hope the Italian people have learned the same lesson.

Leave a Reply