It has been the usual 56-hour day spent in airports under siege from CNN and microwave-burned pizza, cramped into buses, taxis, and the midget seats of American Airlines steerage with two varieties of undrinkable wine-product to wash down the “looks-like-chicken” alternative to the inevitable “pasta” they serve on flights to Italy, but now we are actually in our room at the Hotel Forum. It is a sunny winter’s day, and last night’s rain is still steaming up from the potholes and depressions of the via dei Fori Imperiali, a street that has not been well maintained since Il Duce (who built it as an imperial avenue to connect the Piazza Venezia with the Colosseum) had to leave Rome suddenly for a vacation in the mountains. I throw open the windows and look out upon the Forum of Augustus and the street where the ears and buses ride—their drivers blissfully unaware—on top of the ruins of Trajan’s library. We are almost too happy to be in Rome, and I am struck once again by the disconcerting thought that I may be joining the ranks of so many English and American writers who became expatriates and cultural traitors.

Apart from Hemingway’s first novel and, if you can stand them, some of Henry James’ fiction dealing with Americans abroad, few of these writers set their best works in Italy or France. One exception is E.M. Forster. Despite the popularity of his “foreign” novels (and the films based on them), Forster has been routinely ridiculed by conservatives (especially during the Cold War) as the intellectual cheerleader for the Cambridge “homintern” (as George Orwell described the homosexual arts) types who went to work for the Soviet Union), and the embodiment of the “trahison des clercs” among the chattering class.

In his 1938 essay “Two Cheers for Democracy,” Forster made his famous declaration of disloyalty: “[I]f I had to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend, I hope I should have the guts to betray my country.”

Forster’s bald statement does seem like an invitation to treason, and a sketch of his career docs little to dispel the miasma emitted by his essay—a homosexual Cambridge Apostle and a friend of John Maynard Keynes, Lytton Strachey, and the Woolfs; a partisan of the Boers during the Boer War, a conscientious objector in the Great War, and a critic of imperial policy between the wars; a prominent member of the communist front National Council of Civil Liberties—so many steps in the traitor’s cursus honorum.

The outline, however, is deceiving. Forster was never much of a leftist. He belonged, by his own account, to “the fag-end of Victorian liberalism.” Although he did come to believe that capitalism was destroying society, his conventional social views should have endeared him to conservatives on both sides of the Atlantic: faith in the individual, belief in hard work, appreciation of the middle classes.

Why would such a man advocate treason? The simple answer is that he did not. Forster’s full sentence begins: “I hate the idea of causes,” before going on to saw “and if I had to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend, I hope I should have the guts to betray my country.” He concludes not with a ringing declaration of the duty to aid the class struggle but with an appeal to ancient and medieval notions of loyalty and friendship: “Such a choice may scandalize the modern reader . . . It would not have shocked Dante, though. Dante places Brutus and Cassius in the lowest circle of Hell because they had chosen to betray their friend Julius Caesar rather than their country Rome.”

Of course, Forster may have made an historical error in believing Shakespeare’s Mark Antony—who said “Brutus was Caesar’s angel”—but far from calling for ideological commitment, he was declaring his opposition to even the idea of causes.

Forster’s second novel, The Longest Journey, gives a clearer sense of where he stood. When one Cambridge student makes the case for having loyalty to “the great world,” his friend tells him that

There is no great world at all, only a little earth, for ever isolated from the rest of the little solar system. The earth is full of tiny societies, and Cambridge is one of them. All the societies are narrow, but some are good and some are bad—just as one house is beautiful inside and another ugly . . . The good societies say, “I tell you to do this because I am Cambridge.” The bad ones say, “I tell you to do that because I am the great world—not because I am Peckham,’ or ‘Billingsgate,’ or ‘Park Lane,’ but because I am the great world.”

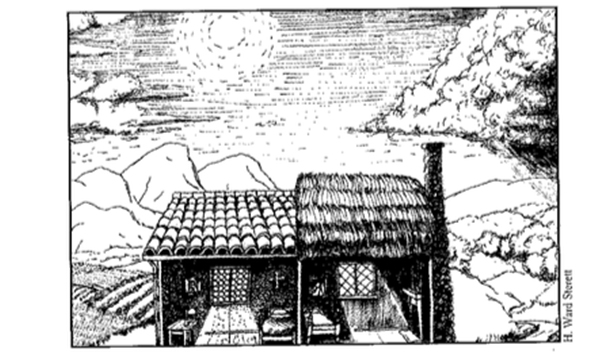

In Forster’s first novel, Where Angels Fear to Tread, the tiny society is formed within the family by the bonds of blood. Lilia is a pretty and somewhat romantic widow whose disapproving in-laws send her to Italy to get a little refinement. To their chagrin, she actually marries one of the locals—an idle and worthless fortune hunter—to whom she bears a child before dying.

Lilia’s sister-in-law, a grave young Englishwoman who had “bolted all the cardinal virtues and couldn’t digest them,” is shocked to discover, as she watches the fortune-hunting Italian father with his child, “that wicked people are capable of love.” Forster, describing the scene, makes the comment that the Italian father’s “desire that his son should be like him, and should have sons like him to people the earth” is “the strongest desire to come to a man.”

The baby’s English stepsister is a rabid Anglican ideologue (if such a thing is possible); she refuses to acknowledge the validity of such an immoral bond between a corrupt man and his son, and, by stealing the child, she is the cause of his death. Gino, at least, was not a Cuban communist, or she might have had additional justification for the kidnapping.

Forster’s best-known heroine, Lucy Honeychurch, is another English girl who is smitten with Italy, where she begins to savor not just art and beauty but something of the Italian passion for living. When her Florence adventure turns sour, she and her companion go on to Rome where she meets a well-todo expatriate, Cecil Vyse, who proposes marriage.

Lucy is given the clear choice of a higher, more “Italian” life with Cecil Vyse, but to take it, she must be disloyal to her family and break with her middle-class experience. “Make her one of us,” her high-toned future mother-in-law tells her son. Cecil says of himself that he is an “Inglese Italianato,” which, as the proverb goes, is “un diavolo incarnato.” Although Cecil is merely affecting “a cosmopolitan naughtiness which he was far from possessing,” he is, after all, a genuine devil, in tempting Lucy into a life of treason against her family and her upbringing.

But, if Italy has taught Cecil to despise his own country, it has taught Lucy to see beauty in her own neighborhood: “How beautiful the weald looked! The hills stood out above its radiance, as Fiesole stands above the Tuscan Plan, and the South Downs, if one chose, were the mountains of Carrara. She might be forgetting her Italy,” drinks Lucy to herself as she looks across the Weald, “but she was noticing more things in England. One could play a new game with the view, and try to find in its innumerable folds some town or village that would do for Florence.”

Part of this new perspective was obviously aesthetic and cultural; it was also moral. As a conventional radical, Lucy had been learning to despise the suburban bourgeoisie and anyone outside the charmed

circle of rich, pleasant people, with identical interests and identical foes . . . But in Italy, where anyone who chooses may warm himself in equality, as in the sun, this concept of life vanished. Her senses expanded; she felt there was no one whom she might not get to like, that social barriers were irremovable, doubtless, but not particularly high. You jump over them just as you jump into a peasant’s olive garden in the Apennines, and he is glad to see you. She returned with new eyes.

The communists and expatriates are wrong: Loving Italy is not incompatible with loving your own country or your hometown. This was something the ancient Romans understood. They could worship their local gods in Britain or Armenia while still acknowledging the power of Capitoline Jupiter or Sol Invictus. They could, like Diocletian, govern the known world and never give up their longing for their native province. In fact, Diocletian retired to Dalmatia to raise cabbages.

Forster’s education was almost entirely classical, and his dilemma—whether it is better to betray one’s friend or one’s country—was posed long ago by an ancient philosopher, who (according to Cicero) asked if a son should inform on a father who has been robbing a temple or digging tunnels into the treasury. The philosopher thought it would be wrong, arguing that the son should defend his father in court, because it is in the country’s interest to have citizens loyal to their parents.

Any nation requires loyalty from its citizens, but not the self-annihilating loyalty demanded by Nazi Germany, Stalinist Russia, or democratic states that impose loyalty oaths, saying (in the words of Merle Haggard), “If you don’t love it, leave it” to Forster’s tiny societies of family, village, and college.

In the years since the publication of The Longest Journey and A Room With a View, the Great World has been making headway against Cambridge and Billingsgate and Laramie and Milwaukee. Colleges and universities have been absorbed by the state; families are enmeshed in a social-service bureaucracy that would have astounded the creators of the welfare state. In the United States, schoolchildren are asked to turn their parents in for using drugs or for abusing (“abuse” may include any form of corporal punishment) them. The child is forced to choose between betraying his parents and betraying the government that can make such a request.

In the 193O’s, F.M. Forster, a simple novelist who was not used to reflecting too deeply, concluded that people mattered more than principles, even when those principles are embodied in a government apparatus. Ever since, he has been reproached by anticommunists for his disloyalty. In some cases, they have simply failed to read him correctly. But even if they did, there may be few political intellectuals, whether of the right or of the left, who would be willing to defend bolster’s almost feudal sense of personal loyalty.

Through the long years of the Cold War, we got in the habit of defining ourselves by what we opposed, and an imaginary Berlin Wall was built between the “capitalist” right and the “disloyal” left. In the course of the conflict, all of Burke’s “little platoons’ and Forster’s “tiny societies” were conscripted to serve the national ideologies of Russia and the United States and perished in the struggle for the world.

Leave a Reply