“Watch what people are cynical about,” said General Patton, “and one can often discover what they lack.” Since the 1960’s I’ve been watching what are often called revisionist historians trying to destroy the American heroes I grew up admiring. At first I couldn’t understand why such historians would be so hell-bent on tearing down figures the rest of us honored, until it dawned on me they saw in those figures qualities they didn’t have, could never have. It was necessary for them to protect their own psyches by denying the courage and honor possessed by our cherished historical figures. Their denial also relieved them of the duty of trying their best to live up to such standards.

Coming in for his share of attacks during the last several decades is David Crockett. Evidently inspired by the devaluation of Crockett, John Lee Hancock, the director and one of the writers of the movie The Alamo (2004), said he wanted to make certain his Crockett did not remind anyone of earlier movie versions. Hancock’s Crockett is full of self-doubt, tortured by his past, and bedeviled by his image. He is not the charismatic frontiersman who inspired the loyalty and courage of those around him. Reflecting revisionist attacks on Crockett, the movie suggests Crockett never did much of anything. Instead, his derring-do was a creation of early day mythmakers, especially James Kirke Paulding, who wrote The Lion of the West, a play about a fictional character named Nimrod Wildfire.

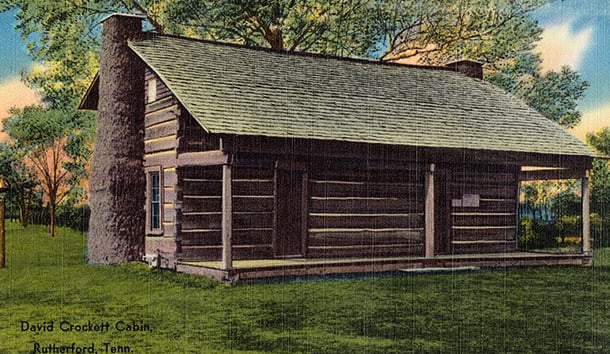

Crockett certainly had tales spun about him that were hyperbolic or entirely fictional, but that was only because his real-life rise from backwoodsman to congressman and his extraordinary adventures were heroic and quintessentially American. He was born in a log cabin near the confluence of Limestone Creek and the Nolichucky River in August 1786 in what would become Greene County, Tennessee, but at that time the area was still part of North Carolina. However, the trans-Appalachian region was neglected by the state government of North Carolina, and two years before Crockett’s birth the settlers created their own state of Franklin. Residents petitioned Congress for admission as the 14th state, but a vote of the states in 1785 fell short of the two-thirds majority required. Franklin continued to operate independently, though—even fighting a battle with North Carolina militiamen—until 1789. Crockett’s life would reflect this independent and defiant spirit of the frontiersmen of Franklin.

Davy was the sixth child and fifth son born to John and Rebecca Crockett in eight years. Rebecca would give birth to another son and two more daughters. John Crockett was the grandson of Irish immigrants to New York, who moved south to Pennsylvania. The next generation went down the Shenandoah Valley and into the mountains of North Carolina. By 1776 they were settled in what would become northeastern Tennessee. John became one of the famous Overmountain Men, who fought at the pivotal Battle of Kings Mountain in 1780. While he was away fighting during the American Revolution, John’s parents were slaughtered by Cherokee, who allied themselves with the British and took advantage of the war to raid and pillage. One of John’s brothers was badly wounded in the attack and left for dead, and another was taken captive by the Cherokee and made a slave.

Born into this environment of pioneering mountain folk, Davy learned marksmanship at a young age, both for hunting and for protection against marauding Indians. He learned how to track and trail animals and men, and how to survive in the wilderness. He learned rough-and-tumble fighting from his older brothers. By the time he was 12 he was going on 400-mile cattle drives to the eastern seaboard. Upon his first visit to the big city of Baltimore, he made his way to the harbor to look upon the great sailing vessels lined up at the wharves. A ship’s captain invited the sturdy youngster aboard and offered him a job. Davy went back to the cattleman who had employed him and said he needed his pay because he was off for Europe. The cattleman had to restrain the young Crockett physically and finally convinced him to return home.

Once back at his mountain home, Davy was in for a surprise. His parents had decided he would benefit from formal schooling. He wasn’t thrilled with confinement in a classroom, but his father was paying for it, and Davy accepted the inevitable. However, one day after school he surprised an older boy who had been bullying him and beat him until he cried for “quarters.” Davy then began playing hooky from school, but after a week the schoolmaster contacted John Crockett. Davy now thought he would be whipped by both the schoolmaster and his own father. When his father came after him with a hickory rod, Davy took off running—and didn’t stop. He was soon on another cattle drive to the eastern seaboard. For the next two years he had more adventures than most people have in a lifetime. By the time he returned home at just shy of 15 years old, everyone was so glad he was alive and well that all was forgiven. He was also now too big to whip. He stood about six feet tall and had developed a powerful build.

Davy learned his father was in debt to an Abraham Wilson, and Davy spent six months working for Wilson as payment. He did the same for the same reason for a John Kennedy. Having helped free his father from debt, Davy now did something for himself. He understood he needed at least the rudiments of an education, and, coincidentally, Kennedy’s son ran a school. Davy struck a deal. He worked for the son two days a week in return for four days a week of schooling. After six months, Davy had become fairly accomplished in reading, writing, and arithmetic, and that would remain the sum total of his formal education.

It was also at this time that he began entering shooting matches and impressing all those present with his marksmanship. At 17 he often outshot all the men, winning a steer or a hog as grand prize. He also began hunting professionally, bringing game, especially bear and deer, to local towns and selling them for their hides and meat. His reputation began to grow, but evidently not enough to win himself a girl. Twice he took aim on girls, only to learn they were already betrothed. Then at a dance in 1806 he met the beautiful Mary Polly Finley. After several reels with Polly, Crockett knew he had found the one. He courted her for several months, and they fell in love. Polly’s mother, the former Jean Kennedy, was initially impressed by the young man but soon was trying to dissuade her daughter from marrying him. This David Crockett was recklessly adventurous. Polly deserved a settled man with property.

It became a battle between Crockett and Mrs. Finley. Finally, Davy simply rode up to the Finley house with a wedding party of relatives, friends, and a minister in tow and said he had come for Polly. William Finley convinced his wife to step outside and talk with Crockett. She surprised everyone by apologizing to her daughter’s suitor for the way she had treated him and invited the wedding party into the Finley home. The minister was probably most relieved of all, and he duly married the young couple—Davy was turning 20, and Polly 18. David Crockett felt blessed. As he put it, he had his own horse and his own rifle, and now his own wife. I “needed nothing more in the whole world,” said Crockett.

Crockett rented property near the Finleys and went to work establishing a farm. He admired the way his wife ran the household, especially her weaving skills, which he attributed to her mother coming from a long line of Irish weavers. Children came quickly—a son in 1807, another son in 1809, and a daughter in 1812. By the time his daughter was born the family had moved farther west twice, and Crockett had become a landowner rather than a renter.

In 1812 war with Britain erupted, and the trans-Appalachia country would be in the thick of it—not fighting British troops, but fighting their Indian allies. The Creeks were especially troublesome. The majority of them supported the British and became known as the Red Sticks. A minority, the White Sticks, supported the Americans. Receiving arms, trading goods, and occasionally military advisors from the British, the Red Stick Creeks began raiding outlying American settlements.

The Creek attack that caused Crockett and other Tennessee boys to volunteer for service occurred on August 30, 1813, at Fort Mims, about 40 miles north of today’s Mobile, Alabama. The so-called fort was not much more than a palisade of logs around the homestead of Samuel Mims. With the Red Stick Creeks on the warpath, American settlers and peaceful Indians crowded into the fort for protection. By late August, the number of people inside the fort reached 500, militiamen accounting for about half.

At noon on August 30 upwards of 1,000 Creek warriors assaulted the fort, hundreds of them pouring through a gate that was left partially open. The militiamen beat back the assault in bloody hand-to-hand fighting, killing most of those who had penetrated the gate, but at a cost of half their own number. Desultory fighting continued for another three hours, and then came another en masse Creek assault. This time the Creeks were able to set the fort ablaze, and everyone inside was forced to flee into the open. The Creeks grabbed small children by the ankles and, swinging them through the air, dashed out their brains on logs. Men, women, and children were scalped and dismembered. Pregnant women had their bellies split open and their fetuses ripped out. One witness recalled the “fearful shrieks of women and children put to death in ways as horrible as Indian barbarity could invent,” which could be heard a half-mile off. About three-dozen Americans escaped, some mortally wounded. Their descriptions of what the Creeks had done reverberated across the frontier. “Remember Fort Mims” became a rallying cry.

The Tennessee legislature authorized the raising of an army of militiamen. Andrew Jackson was named the army’s commander. At the time, Jackson was recovering from a severe wound suffered in a duel. Though he was too weak to get up from his bed, he accepted the appointment, said he’d have an army on the march in nine days, and called for Tennesseans to volunteer for duty. David Crockett was one of those answering Jackson’s call.

As the army moved southward Crockett was put in charge of a small party of men and sent on a scouting mission. He penetrated deep into Creek country and learned the Creeks were preparing to attack. Jackson was not about to wait for the Creeks and instead had his army on the march. Crockett and other mounted volunteers, under the immediate command of John Coffee, raced ahead, until they reached the Creek village of Tallushatchee. There were dozens of cabins and, according to intelligence gathered by the scouts, more than 200 well-armed Red Stick warriors in them.

Coffee had hoped for a surprise attack, but the Indians “began to prepare for action, which was announced by the beating of drums, mingled with yells and war whoops.” Coffee had his volunteers encircle the village and then sent a portion of his force in a feint at the center cabins. The Red Sticks thought they could overwhelm the small force and charged out of the cabins. The Tennessee boys fired once and retreated, with the Indians whooping and pursuing. With the trap sprung, Coffee’s main force swiftly closed on the surprised warriors, who now turned and raced for their cabins.

“The enemy fought with savage fury,” said Coffee in an after-action report,

and met death with all its horrors, without shrinking or complaining: not one asked to be spared, but fought as long as they could stand or sit. In consequence of their flying to their houses and mixing with the families, our men, in killing the males, without intention, killed and wounded a few of the squaws and children.

Those cynics who think Coffee might have written a disingenuous report will have a difficult time explaining the 84 women and children taken prisoner. One of the children, a ten-month-old boy orphaned by the fight, was about to be killed by squaws when the troops intervened. He was carried to Andrew Jackson, who took him into his tent and coaxed him to drink a mixture of brown sugar and water. The boy became Andrew Jackson, Jr.

A week later at Talladega, Crockett was in an even bigger battle when a thousand Creek warriors came rushing out of the woods, in Crockett’s words, “like a cloud of Egyptian locusts, and screaming like all the young devils had been turned loose, with the old devil of all at their head.” When the furious fight ended, 300 Red Stick warriors lay dead on the battlefield, and dozens of others were probably dying elsewhere. Fifteen of the Tennessee boys died in the battle, and more later died of their wounds. Crockett would continue to fight in the war with the Red Sticks—including the battles at Emuckfaw Creek and Enotachopco Creek—and in the Seminole campaign that followed, serving two three-month enlistments and rising from private to sergeant.

In John Lee Hancock’s The Alamo, Jim Bowie tells Crockett, “those are not bears out there”—as if Crockett had never fought anything that shot back.

Crockett was finally back home in 1815, but his bliss was short-lived. His wife, Polly, fell ill and died. A year later he married Elizabeth Patton, a widow with two children. She had lost her husband in the Creek War. Crockett would father three children by her. He moved west again in 1817 and became justice of the peace for the newly established Lawrence County. The next year he was elected lieutenant colonel of the local regiment of the Tennessee Militia. In 1821 he was elected to the Tennessee General Assembly, and reelected in 1823. He was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1826, and reelected in 1828. He lost his reelection bid in 1830, but then won his seat back in 1832. When he lost again in 1834, he started thinking about moving to Texas.

Crockett was convinced that Texas would soon become independent of Mexico, and he felt he had a duty to play a role in that. His youngest child, Matilda, watched him leave home.

He was dressed in his hunting suit, wearing a coonskin cap, and carried a fine rifle presented to him by friends in Philadelphia. . . . He seemed very confident the morning he went away that he would soon have us all to join him in Texas.

By the time Crockett reached Memphis, some 30 like-minded friends had joined him. The night before they crossed the Mississippi a celebration was held in his honor. Bar-hopping finally took the revelers to Neil McCool’s. They hoisted Crockett up on a counter, and he told the crowd that since his constituents had failed to re-elect him they could “go to hell, and I’ll go to Texas.”

Crockett and his companions arrived at the Alamo on February 8, 1836. Santa Anna and his army arrived two weeks later, and the siege began. Several different times during the siege the sharpshooting of Crockett and his Tennesseans was instrumental in driving back the Mexicans. After one of the battles, William Travis wrote, “The Hon. David Crockett was seen at all points, animating the men to do their duty.” Following 13 days of continual artillery bombardment, Santa Anna launched a massive assault on the morning of March 6. According to Susannah Dickinson (or Dickerson), who was there throughout the siege and was one of the noncombatants crowded into the chapel at the end, Crockett stepped into the chapel and said a prayer before joining his Tennesseans defending the south wall. They all fired their rifles until out of ammunition, and then used their weapons as clubs. After 90 minutes of furious fighting, it was over. Dickinson said she “recognized Col. Crockett lying dead and mutilated between the church and the two story barrack building . . . his peculiar cap by his side.”

Those who seem hell-bent on trying to diminish such a man might first want to look inside themselves.

Leave a Reply