It’s difficult to explain today that, from the 1920’s through the mid-1960’s, track and field was a major sport in Southern California. There were several reasons for this. There was no Major League Baseball anywhere on the West Coast—Chicago and St. Louis were the westernmost cities to field teams. We had only a minor-league circuit, the Pacific Coast League. Our teams in Los Angeles were the Angels and the Hollywood Stars. The Brooklyn Dodgers didn’t relocate to L.A. until 1958. Like baseball, pro basketball didn’t reach the West Coast. The Minnesota Lakers didn’t move to Los Angeles until 1960. Then, too, television didn’t really begin broadcasting sports to a significant degree until the mid-1950’s. That would eventually hurt track and field because it didn’t fit into a predictable time slot like the other sports, and commercials couldn’t be aired between innings or periods or quarters. This meant the other sports got ever increasing airtime, while track and field faded from television.

Many of our greatest sporting heroes in Southern California were track stars. We had world-record holders and Olympic medalists in abundance. The climate was ideal for track and field, and the sport simply blossomed. By the 1920’s thousands would attend a big meet, and Charley Paddock of Los Angeles was setting world records in the sprints. By the beginning of the next decade it was Frank Wykoff of Glendale setting records in the dashes, and by the late 1940’s Mel Patton of West L.A. was breaking those set by Wykoff. Patton would hold the record in the 100 until the early 1960’s. In nearly every event there were California boys among the top athletes in the country, and often in the world.

A teenager from Santa Monica began making a name for himself by the time he was a senior in high school. William Parry O’Brien, Jr., was born in January 1932 in Santa Monica. His father worked as an electrician at the studios but had played minor-league baseball; he had been born in California, but his father was from an Irish immigrant family in Michigan. Junior’s mother, the former Hazel Tobin, was born in Santa Monica. Her father, a Gaelic speaker, had emigrated from Ireland with his family as a child, and as an adult he worked as a carpenter and settled in Santa Monica. Hazel and her five siblings were all reared there.

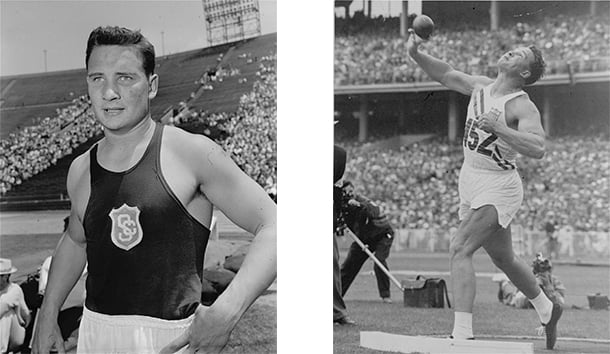

During the fall of 1948, Parry O’Brien, as he was known by then, helped lead Santa Monica High School to the state championship in football as an end. He was a fine broth of a boy, standing 6’3″ and weighing 215 lbs. Despite his size, when spring came he ran the dashes and was a member of the sprint relay team. His best event, though, was the shot put. He set records for Samohi and then won the state championship with the 16-pound shot, taking third with the 12-pound.

He attended the University of Southern California on an athletic scholarship, intending both to play football and to put the shot. However, an injury during a football practice as a freshman convinced him to quit the gridiron. “You can be either an All-American or an Olympic champion,” a teammate told him, according to a 1956 article in Time. “There are at least 33 All Americans every year. But there is only one Olympic champion—every four years.” Recovering from his injury, O’Brien decided on dedicating himself to the shot put. It suited his personality. “I wanted to be able to take the credit or the blame for what I did myself,” said O’Brien. “I always wanted to be a soloist.”

As a freshman at SC, O’Brien continued running sprints, but it quickly became obvious that his real talent lay in putting the shot. By the time he was a sophomore he had added 25 pounds of muscle and was now tipping the scales at 240. Although only 19 years old, he was ranked No. 3 in the United States and No. 4 in the world. That was not good enough for the teenager. He began experimenting with a new style of putting the shot. Shot putters normally stood sideways at the back of the ring and then slid across the ring as fast as possible to gain momentum, twisting forward at the last second to let the shot fly. Quick and agile, O’Brien decided to stand facing 180 degrees from the front of the ring. He then squatted deeply on one leg and kicked with his other leg to begin accelerating across the ring. His last-second twist to the front covered more degrees of rotation and generated more torque than the standard method. What would become known as the O’Brien Glide revolutionized the event.

At the Amateur Athletic Union track and field championships in 1951, O’Brien won by defeating defending champion and world-record holder Jim Fuchs. The AAU rewarded O’Brien and other athletes with a summer trip to European meets. In Italy, shot putters and newspaper reporters were stunned at the strength of O’Brien’s fingers. They noted how he released the shot from his fingers rather than from the palm of his hand. When the Italian champion tried to emulate the style, he injured himself. “O’Brien is the prototype of the agile thrower,” said one newspaper, “not overweight, powerful but quick. Watching him running on the grass of the field during the warm-up was an astonishing experience; apart from the big frame, you would have thought he was a sprinter.”

During the 1952 season O’Brien began racking up a string of victories that was ended only in the Olympic Trials by Darrow Hooper of Texas A&M. O’Brien reversed that defeat to win the gold medal at Helsinki, breaking the Olympic record with a put of 57′ 1½”. Hooper took the silver, and Fuchs the bronze, for an American sweep. Parry O’Brien was now a national figure. Locally, he had been known to nearly everyone since his days at Samohi. This was especially true for those of us in the immediate Santa Monica area. My home was Pacific Palisades, the next stop up the coast. Going down into Santa Monica, then a conservative family-oriented city, was a regular trek for most in the Palisades, which had only a very small commercial area. For clothes, shoes, furniture, tires, cars, and a hundred other things it was Santa Monica. I even went there to be born—in a hospital three blocks from the O’Brien family home.

Parry O’Brien’s Olympic victory was the beginning of a winning streak that extended through 116 consecutive track meets. In May 1953 at the Fresno Relays O’Brien broke Jim Fuchs’s world record with the first put over 59′. A month later he broke his own record at the Compton Relays. In 1954 O’Brien broke the record six times, twice in one meet. In May of that year he broke through the “60-foot barrier” with a throw of 60′ 5¼”. He finished the season with a world record of 60′ 10″. He failed to break his record in 1955 but remained undefeated and won the gold medal at the Pan American Games in Mexico City. He also competed in the discus and took the silver.

O’Brien was back to breaking his world record in 1956. Seven times he set a new mark, culminating in a gargantuan heave of 63′ 2″ in the Olympic Trials at Los Angeles. He was a bit off form in the poor weather at Melbourne, but still returned home with a gold medal and a new Olympic record of 60′ 11¼”. Big, brawny Bill Nieder, a senior at the University of Kansas, took the silver. O’Brien was only the second person to win the shot put twice in the Olympics. He went on the cover of Time in December 1956.

By this time my older brother was taking me to one or another of the major track meets in Southern California. Watching O’Brien perform always put you on the edge of your seat. He could break the world record on this throw—or the next. He was all concentration and focus. He ignored other competitors. Dave Davis, who was ranked No. 3 in the world in the shot put in 1958 and No. 4 in 1959 and 1960, described what it was like going up against O’Brien. “Sure, it bothers me to compete against him,” said Davis.

He makes it that way on purpose. He puts and then he walks away and ignores you. You feel the other guys looking at you when you’re getting ready to put, but not O’Brien. He acts like he’s the only one there. You know he’s not worried about you. . . . He bugs me.

O’Brien dominated the sport and remained undefeated in 1958 and 1959, although Bill Nieder, Dave Davis, and Dallas Long were edging closer and closer to his world record. Then in a meet in Santa Barbara in March 1959, Long tied O’Brien’s record of 63′ 2″. O’Brien answered with a record of 63′ 4″ in August. Moreover, O’Brien won the AAU championship and took the gold medal in the Pan American Games in Chicago with a put of 62′ 6″. Long was second at 60′ 9″, and Davis far back in third with a 55′ 10″ heave. Evidently, the famous O’Brien psych was working. O’Brien finished the year ranked No. 1.

Nonetheless, it was clear the bigger and younger Nieder, Long, and Davis would soon be passing O’Brien. This was in an era when track athletes were amateurs and prohibited from making anything from their sport. They had to hold down a job and train in their spare time. It took a toll. O’Brien was a vice president at a bank. In January 1960, he turned 28, and that was considered old.

Early in March at a meet in the L.A. Coliseum, Long broke O’Brien’s world record with a toss of 63′ 7″. This time it wasn’t O’Brien but Nieder who immediately broke Long’s record. In mid-March Nieder went 63′ 10″. Long came back with 64′ 6½”. Then, in April at the Texas Relays, Nieder hit 65′ 7″. However, at the Olympic Trials in July at Stanford, Long took first, O’Brien second, and Davis third. Nieder was a disappointed fourth. Perhaps the O’Brien psych was on again.

The plot then thickened. Davis injured his hand and gave up his spot on the Olympic team to Nieder. At the Olympics in Rome, O’Brien, now the grand old master, was leading going into the final round with an Olympic record of 62′ 8½” followed by Long at 62′ 4½”. On his last throw Nieder overcame the O’Brien psych and let rip with a mighty heave of 64′ 7″. Nieder had the gold medal and the Olympic record, but O’Brien walked away with a silver medal to go with his two golds. No other shot putter had ever done that.

In 1961 O’Brien, consistent in the 62- and 63-foot range, finished No. 3 in the world behind Dallas Long and Arthur Rowe of Britain. Nieder had left track and field to try his hand at boxing. The following year was an off year for O’Brien, and he ranked only tenth in the world. Just when everyone thought he was finished, he came back with a vengeance in 1963. It was the year a friend of mine got me to lift weights with him at a gym for football. Also working out at the gym was Parry O’Brien. He’d shoot the breeze with us before or after, but once he started a workout it was all focus and concentration. His intensity was almost otherworldly. I wasn’t surprised he finished the track season ranked No. 4 in the world.

I watched O’Brien continue with the same intensity in the gym in 1964, and then I watched him at the Olympics Trials take third with a 63′ 1¾” behind Dallas Long and Randy Matson. O’Brien was off to Tokyo and his fourth Olympics. He proudly carried the Stars and Stripes at the opening ceremonies. Long took the gold, and Matson the silver, but O’Brien was edged out of the bronze by Vilmos Varju of Hungary.

In 1965 O’Brien was not ranked among the top-ten shot putters in the world for the first time in 15 years. Seven of those years he had been ranked No. 1. Although married with two daughters, he went back to the gym and the ring in 1966, and recorded his best throw ever, 64′ 7″. He finished the season ranked third in the world.

After the 1966 season he finally called it quits. He had won eight AAU championships in the shot put, and one in the discus. He had won another nine indoor AAU championships in the shot put. He had broken the shot-put world record ten times. He had won two gold medals and one silver in the Olympics, and two gold medals in the Pan American Games. He was named to the National Track and Field Hall of Fame in 1974, the U.S. Olympic Hall of Fame in 1984, and the University of Southern California Hall of Fame in 1994. The Samohi boy had done OK.

Leave a Reply