Though the mountain men were responsible for blazing nearly every trail to the Pacific Coast, discovering the natural wonders of the Trans-Mississippi West, and providing the muscle that fueled the fur trade—a major component of the American economy—few gained national recognition. An outstanding exception was Kit Carson. During the 1840’s and 50’s, John C. Frémont and his wife, Jessie, wrote glowingly of Carson and his exploits. A century later I began learning of Kit Carson. He was still a well-known historical figure and part of any student’s education in California. He was portrayed heroically in books and articles and as a character in movies. He was also the subject of a television series. He was one of those figures who made me proud to be an American and whetted my appetite for grand adventures.

Ask students today about Kit Carson, and they will probably draw a blank. No room any longer for such heroes in their politically correct textbooks.

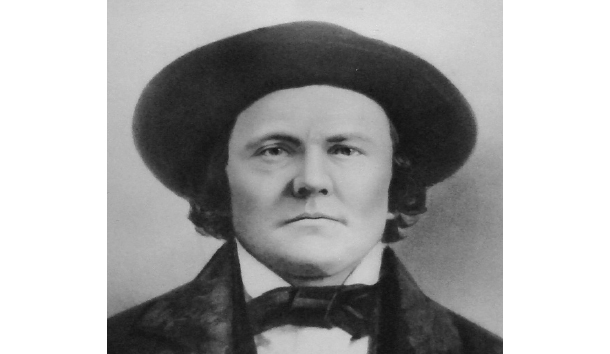

Born in Madison County, Kentucky, in 1809 to a family of Scotch-Irish pioneers, Christopher Houston Carson was destined for greatness. By the time he was two his family had picked up and migrated westward to a farm near Boone’s Lick, Missouri. He was not quite nine when his father was killed while felling a tree. Kit, as he had been called from infancy, dropped out of school to work full-time on the family farm. He hunted in his spare time, helping to put meat on the table for the family.

At 14 years old he was apprenticed to David Workman, a saddle maker in the town of Franklin, situated at the eastern terminus of the Santa Fe Trail. Although young Carson hated both the work and confinement in the saddle shop, it was a blessing in disguise. Many of the shop’s customers were traders, teamsters, or scouts on the Santa Fe Trail. Their tales of the way west and what lay over the horizon fired the boy’s imagination. At 16, in August 1826, he ran away from his apprenticeship and signed on as a wrangler with a trade caravan headed for Santa Fe. Workman evidently sympathized with Carson. The saddle maker ran an advertisement in the local newspaper, as required by law, reporting the runaway apprentice, but waited until October to do so, ensuring that Carson would be long gone. If the delay weren’t enough to reveal Workman’s feelings, then the reward he offered was. Said the advertisement published in the Missouri Intelligencer,

Notice is hereby given to all persons, THAT CHRISTOPHER CARSON, a boy about 16 years old, small of his age, but thick set; light hair, ran away from the subscriber, living in Franklin. . . . All persons are notified not to harbor, support or assist said boy under the penalty of the law. One cent reward will be given to any person who will bring back the said boy.

After 900 miles of hard work and adventures on the trail, Carson arrived in Santa Fe at about the same time Workman’s advertisement was published. A few of the traders were going on to Taos, and Carson eagerly joined them. At Taos he bumped into Matthew Kinkead. The Carson and Kinkead families had been close neighbors and friends in both Kentucky and Missouri, and Kinkead, who had been in Taos for more than a year, immediately took Carson under his wing. Carson worked at various jobs but mostly as a teamster, driving freight wagons to El Paso. Having a facility for languages, he quickly learned Spanish. He would later develop fluency in a half-dozen Indian tongues.

In 1829 and not yet 20 years old, Carson joined a fur-trapping brigade of some 40 men organized by the veteran frontiersman and trapper Ewing Young. The Tennessee-born Young led the party into Arizona, most of which was still virgin beaver country. There was a good reason why so few trappers had ventured into the territory: the Apache, who delighted in torturing and killing their enemies, especially the Pima and Papago. Young was well acquainted with the Apache and their tactics, though, and had his mountain men well prepared for Apache ambushes. In several fights the trappers inflicted grievous casualties on the enemy warriors. This enabled the trappers to harvest a rich bounty of pelts, which Young sent back to Taos with half of his men. He then set out with his remaining trappers, including Carson, for California. In their trek across the deserts of Arizona and California they suffered terribly from thirst and hunger, but the party arrived intact at Mission San Gabriel.

Carson thought the mission, with its vast orchards, nearby meandering stream, and balmy air, was “a paradise on earth.” Within a day, though, the Americans were off again, headed north to trap the San Joaquin and Sacramento valleys. They worked their way as far north as the Pitt River before turning back south. Young sold their catch of furs to a trading ship at anchor in San Francisco Bay and then, after pleas for help, aided local Mexicans in a fight with Indians and in the recovery of stolen horses. Before leaving California, Young thought he’d take his ornery band to visit Los Angeles, a dusty hamlet of only a few hundred souls but nonetheless the province’s second-largest city. Mexican officials in Los Angeles demanded to see the trappers’ passports. When Young replied they had none, the officials said they would be arrested. The officials thought better of it, however, when Young’s buckskin-clad, heavily armed, and rough-looking mountain men came up.

On the return journey to New Mexico the mountain men camped, rested, and trapped for nine days along the Colorado River. This evidently gave the local Indians plenty of time to grow envious of all the horses, provisions, and equipment the trappers possessed. Suddenly one morning, 500 Indians appeared at the mountain-man camp. “They pretended friendship,” said Carson, “but . . . we mistrusted them and . . . discovered where they had their weapons concealed, and then it became apparent to us that their design was to murder the party.” Upon learning the chief of the Indians spoke Spanish, Carson told him in no uncertain terms that the Indians must leave the camp within ten minutes or be shot. One of the trappers remarked that Carson’s voice rang out loud and clear, his eyes flashed, and he grasped his rifle “with all the energy of an iron will.” Evidently impressed by Carson, the chief quickly relayed Carson’s message, and as suddenly as the Indians had appeared they were gone. The mountain men were also impressed by Carson, and had to remind themselves that he was only 20 years old.

The mountain men trapped the Gila River eastward across Arizona and along the way, after brief battles, recovered two horse herds stolen by Indians from Mexicans in Sonora. Early in 1831 the party arrived back in New Mexico. The trapping expedition had been a fabulous success, and every trapper was paid handsomely. Carson had more money than he had ever seen and was delighted, never thinking, as he would later say, his life had been risked in gaining it. By the fall of 1831 he was off again, this time joining a fur-trapping brigade led by Tom Fitzpatrick, the Irish-born mountain man who was well on his way to becoming a legend himself. Fitzpatrick led the trappers north to the Platte River, then west along the Sweetwater to the Green River. From there they reached Jackson’s Hole, then across the Grand Tetons to Pierre’s Hole and northwest to the Salmon. They eventually reached the Columbia.

The country that Fitzpatrick led Carson and the other mountain men through was the most spectacular and beaver-rich in all of North America. Carson would spend the next decade of his young life there, have enough adventures for a dozen men, and develop into one of the most respected of mountain men. Although of small stature, he never backed away from a fight and reacted ferociously to bullies. At the rendezvous of 1835 a trapper, described as a very large and very strong Frenchman, was bragging about all the men he had whipped into submission and said he particularly enjoyed thrashing Americans. Carson sprang to his feet and exclaimed to the Frenchman, “I’ll rip your guts.” The Frenchman said nothing but mounted his horse and rode out in front of the camp, daring Carson to join him. Carson quickly jumped on a horse and galloped up to the Frenchman. Both men drew guns and fired at precisely the same moment. All the mountain men there said they heard but one report. The Frenchman’s round creased Carson’s skull, taking skin and hair with it. Carson’s round went through the Frenchman’s arm, causing him to drop his weapon. Carson drew a second pistol and prepared to deliver the coup de grace. The Frenchmen now began begging for his life. Satisfied that he had humiliated him, Carson turned and rode away. “During our stay in camp,” said Carson, “we had no more bother with this bully Frenchman.”

John C. Frémont never left on an expedition without first hiring mountain men as guides, including Tom Fitzpatrick, Joe Walker, and, especially, Kit Carson, who served with Frémont for more than four years and participated in four of Frémont’s five expeditions through the West. While with Frémont, Carson took part in both the Bear Flag Revolt and the Mexican War in California. Commodore Robert F. Stockton, who took command of American forces in California during July 1846, made Carson a lieutenant. When Stockton declared California secured in August, he ordered Carson to carry dispatches across the continent to President James Polk.

Carson organized a small party of men and headed east. About the time Carson left California, Brig. Gen. Stephen Kearny and his 2,500-man Army of the West reached Santa Fe, New Mexico. After the surrender of the Mexican forces, Kearny left the bulk of his soldiers in New Mexico and headed for California with 300 dragoons (cavalry) and his trusted scout, former mountain man Tom Fitzpatrick. Early in October, they ran into Carson, who told them California had been conquered and hostilities ended. Kearny sent all but 100 of his dragoons back to Santa Fe and ordered Carson to lead him to California. Carson wasn’t happy with the change of plans but complied with the order when Kearny said he’d have Fitzpatrick take Carson’s dispatches to Washington.

Near the Colorado River crossing, the American force captured several Mexicans and learned California was now in a state of revolt. Kearny decided to head for San Diego, where he thought he’d find Commodore Stockton, rather than Los Angeles, his earlier objective. At San Pasqual, some 40 miles shy of San Diego, he ran into a 150-man force of rebellious Mexican Californians led by Andrés Pico, brother of the former governor, Pío Pico. In the best of cavalry tradition, Kearny ordered a charge. However, not only was Kearny’s force outnumbered, but his men were mounted on mules—a few on horses—and all exhausted after the trek from New Mexico. The Mexicans were wealthy rancheros or the sons of rancheros and were mounted on the finest horses in California. Moreover, they were famous for deftly wielding long lances from horseback.

The battle of charges, retreats, and skirmishes continued intermittently for the better part of two days, mostly in favor of the Mexicans. The Americans found few of their pistols or rifles would fire after their powder had been dampened earlier while crossing the coastal mountains in a rainstorm. They also learned their sabers were generally ineffective against the long lances of the Mexicans. Most of all, though, the Americans quickly realized their exhausted mules were of little use against fresh horses. By the end of the second day, Kearny had lost 18 men, and a dozen others, including Kearny himself, had been wounded. Nonetheless, the Mexicans suffered casualties also, and Kearny was able to take control of a small hill and hold the high ground. The Mexicans fell back and waited, knowing the Americans, without food or water, and with little ability to treat their wounded, would sooner or later have to leave their defensive position.

When darkness fell on the second day, Carson and Edward Beale volunteered to attempt to slip through the Mexican lines and reach Stockton at San Diego. The two men tucked their boots into their belts to move more quietly and alternately crept and crawled through the Mexican force. Having lost their boots in the effort, they covered the rest of the distance barefoot. Stockton sent a force of 200 Marines and sailors to San Pasqual. Upon their approach, the Mexicans mounted their fine steeds and galloped away.

In January 1847 the Mexican rebels surrendered, and Andrés Pico signed the Treaty of Cahuenga. He and his compatriots were allowed to return to their ranchos, although they could have been executed. They were all outlaws because they were fighting after the Mexican authorities in California had formally surrendered at Monterey. Carson was now dispatched to Washington again. This time he made it all the way, stopping off at St. Louis to visit with Sen. Thomas Hart Benton, Frémont’s father-in-law and one of the nation’s greatest advocates of Manifest Destiny. In Washington, Carson met with President Polk, Secretary of State James Buchanan, and Secretary of War William Marcy. The runaway apprentice had come a long way.

Carson married and settled in Taos. His attempt at spending his remaining years as a peaceful family man were in vain. He was prevailed upon to lead several expeditions against marauding Indians, who had grown accustomed to raiding Mexican farms with impunity and, at first, saw no reason to stop the depredations just because Americans were now in charge. Carson was so successful in fighting Indians and in making peace with them that he was appointed the Indian agent for northern New Mexico.

When the Civil War erupted, Carson resigned as Indian agent and joined the New Mexico Volunteers with a commission of colonel. He commanded two battalions at the Battle of Valverde in 1862, which stopped Confederate plans for capturing the gold mines of Colorado. The Apache and Navajo took advantage of the Civil War to renew their raiding in New Mexico, and Carson led expeditions against both, which ended in the “Long Walk” for the Navajo. Carson would also fight Kiowa and Comanche at the Battle of Adobe Walls in the Texas panhandle in 1864. By the end of the Civil War, Carson had been brevetted brigadier general.

Following the war, Carson returned to his family, but duty called again and again. Although Carson’s health was deteriorating, in 1868 the federal government requested he bring a delegation of Ute chiefs to Washington to negotiate a treaty. Transportation had changed dramatically since his cross-country trip from California during the Mexican War. This time it was stagecoach from Fort Lyon, Colorado, to Fort Hays, Kansas, then railroad all the way to Washington.

Shortly after Carson returned home, his wife gave birth to their eighth child. Complications set in, and within two weeks his wife had died. He followed her to the grave a month later when an aortic aneurysm ruptured.

Each year we take a motorcycle ride through the Sierra Nevada and are reminded of Kit as we climb through Carson Pass and race alongside the Carson River. Descending the eastern side of the Sierra, a left turn onto Highway 395 leads to Carson Valley and north to Carson City, the capital of Nevada. Too bad our younger generations will know nothing about the origin of these names.

Leave a Reply