In 1882 Congress took steps to control Chinese immigration with the passage of “An Act to execute certain treaty stipulations relating to Chinese.” The act later became known misleadingly as the Chinese Exclusion Act. In high schools and colleges it’s taught that the act was simply another example of American racism.

The real story is more complex, requiring (among other things) some understanding of the economic impact of Chinese laborers on the wages of American workingmen in California in the mid-19th century. That level of scholarship is evidently too much for educators today.

The first Chinese arrived with the Gold Rush in 1849 and continued to pour into California throughout the 1850s and ’60s. From the start they were set apart not only by their racial and cultural characteristics, but also by their goals. The Chinese did not seek permanent residency and Americanization like other immigrants. Instead, they wanted only to sojourn in California, earn money, and return to China.

Chinese emigration was a consequence of overpopulation, famine, and political chaos in China, especially in the Pearl River Delta region, which includes the cities of Canton and Hong Kong. Tens of thousands of young men sought opportunity overseas. Hong Kong was the port of departure.

Immigration to California followed a pattern established more than a half century earlier, when three types of Chinese emigrants were sent overseas to destinations such as the Philippines and Singapore: indentured servants, contract laborers, and coolies. Although all three types were commonly called coolies, the true coolies were only those kidnapped and sold into service.

Wealthy Chinese merchants and their enforcers controlled the system, not Americans. The great majority of the immigrants to California came as indentured servants, who remained under the control of the merchants until their period of indenture was completed and all debts to the merchants were paid. California’s constitution prohibited indentured servitude but, for the most part, the Chinese obediently accepted the system. This is because they expected that the rest of their lives would be lived in their homeland, not here.

It was also because of their sojourner status that the Chinese rejected the values of American society and carefully maintained their own culture. That culture was radically different, including not only a language unrelated to English and a religion unrelated to Christianity, but also different customs, clothes, food, and intoxicants.

Secret societies were another aspect of Chinese culture that was alien to the American way of life. When the Chinese migrated overseas, chapters of those societies migrated with them. The chapters were known as tongs, from a Chinese word meaning assembly hall.

Tongs became especially important in the United States, ensuring not only that immigrants met their obligations to the Chinese merchants but also providing extralegal political and social structure for Chinatowns. The tongs also controlled opium trafficking, gambling, and prostitution, and thereby established a massive income stream. The various tongs often came into conflict, sometimes brutally violent, over regulation of opium dens, gambling halls, and brothels.

Despite all this, it was the threat to the American workingman that caused the greatest problems. Big business in California could contract with a Chinese merchant in San Francisco or Hong Kong for workers at half or less than the cost of Americans doing the same job. The effects of this were first seen in mining. Gangs of Chinese workers were brought into the mining camps of California’s Mother Lode Country until they accounted for 10 percent or more of the population. Consequently, the California legislature passed laws in 1850 and 1852 that required foreign miners to buy a license and pay a tax.

In 1852 California governor John Bigler attempted to get the state legislature to limit Chinese immigration into California and prohibit the exportation of California gold to China. Bigler’s desires reflected those of the great majority of workingmen and miners but not those of big business, which benefited from cheap labor, nor of the wealthy residents of San Francisco, who enjoyed having houseboys, cooks, launderers, and gardeners for a pittance.

When an economic contraction occurred in California in the mid-1850s following the boom years of the Gold Rush, and unemployment became widespread, the legislature passed a head tax of $50—equivalent to $5,000 today—on immigrants “not eligible for citizenship.” This would have sharply reduced Chinese immigration, but the state’s supreme court ruled the tax unconstitutional.

The economy began recovering during the late 1850s and then boomed again with the great Comstock Lode strike in Nevada. Moreover, by the early 1860s, thousands of young California men enlisted to serve in the Civil War. Jobs were plentiful once again and agitation against cheap Chinese labor subsided somewhat. Even when Charles Crocker of the Central Pacific Railroad contracted with Chinese merchants for thousands of Chinese workers, there wasn’t much controversy because his construction crews were growing so rapidly that white workers were not laid off and those seeking jobs were hired.

By the early 1870s, California’s economy was slowing again. In 1871 Newton Booth won the governorship on a platform that stressed Chinese exclusion and railroad regulation. Following his lead, the legislature passed several acts to decrease Chinese immigration, but they were struck down by state or federal courts, which cited the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause, the Burlingame Treaty’s guaranty of Chinese immigration to the U.S., and the 1866 Civil Rights Act’s prohibition of immigration taxes.

The Panic of 1873 financial crisis sent unemployment soaring again and by the mid-to-late-1870s labor leaders were pleading with both state and federal governments to do something about cheap Chinese labor. Rising to leadership of the workingmen in San Francisco was County Cork-born Denis Kearney. He left his home in Ireland as an 11-year-old cabin boy after his father died and sailed around the world more than once before settling in San Francisco and becoming a naturalized American citizen.

Kearney had almost no formal education but was a highly intelligent and voracious reader. He became a member of the Lyceum of Self-Culture, which featured speakers, readings, discussions, and debates. Kearney was known at the Lyceum as a brilliant debater.

Kearney developed his own freighting business, hauling goods around San Francisco. He started with one wagon and soon had a fleet of five. By the mid-1870s he was fairly prosperous. He had also married Irish immigrant Mary Ann Leary and had three children. He wasn’t the most likely candidate to become a radical agitator but he was outraged at the way big business controlled the city of San Francisco and the state of California, at the Southern Pacific’s monopolistic control of rail traffic in the state, and by the Chinese undercutting the wage scale of the workingman.

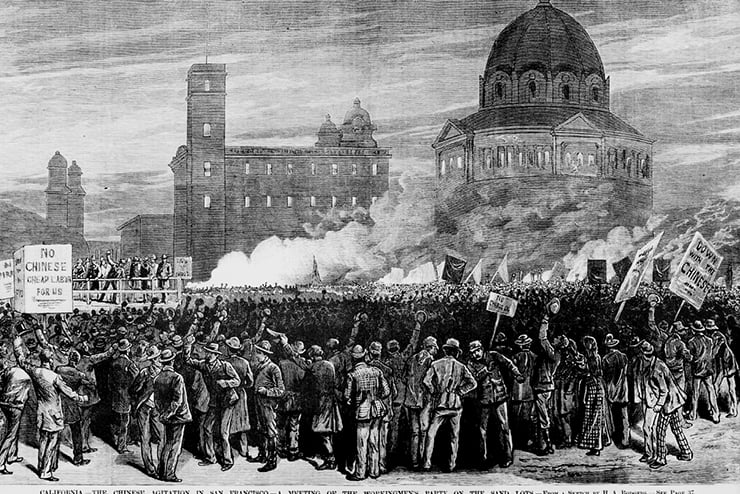

In the fall of 1877, he was responsible for founding the Workingmen’s Party of California. He railed against cheap Chinese labor but more so against the Nob Hill millionaires who became rich off that labor. Corrupt politicians and the monopolistic Southern Pacific also felt the lash of Kearney’s rhetoric.

Kearney’s open-air speeches were powerful, poignant, and incendiary. He drew crowds of thousands and was arrested again and again for inciting violence. On the night of Oct. 29, 1877, he led a crowd of thousands to Charles Crocker’s mansion on Nob Hill and declared the directors of the Central Pacific Railroad a pack of “thieves” who would “soon feel the power of the workingmen.” Throwing down the gauntlet, he gave them “three months to discharge their Chinamen…or take the consequences.”

The Workingmen’s Party campaigned hard for the election of delegates to the California constitutional convention of 1878-79 and won a surprising one-third of the total. There were so many factions represented at the convention, though, that the new constitution was more compromise than radical change. However, a railroad commission was created to regulate railroads, and employment of Chinese on public works was prohibited.

Kearney was disappointed in the new constitution but had cause for celebration when the Workingmen’s Party won decisive victories in municipal elections in San Francisco in September 1879, securing the offices of mayor, sheriff, auditor, tax collector, district attorney, and treasurer.

The success of the Workingmen’s Party of California forced President Rutherford B. Hayes and Congress to deal finally with the immigration of Chinese laborers to the Golden State. Since the Burlingame Treaty prohibited any restrictions on Chinese immigration, President Hayes sent a delegation to China to negotiate a new treaty. The Chinese subsequently agreed that the U.S. could “regulate, limit, or suspend” the immigration of Chinese.

This allowed Congress to pass the Chinese Exclusion Act. However, the act did nothing more than suspend “the coming of Chinese laborers to the United States.” Laborers already here were not expelled, and if they wanted to return to China and then reenter the U.S., they were free to do so. The act did not prohibit the entry into the U.S. of Chinese businessmen, teachers, tourists, government officials, or any other class of Chinese but laborers.

There may have been widespread anti-Chinese sentiment in California, and in the U.S. generally, but the 1882 act was directed only at Chinese laborers who, for more than three decades, had dramatically undercut the wage scale for the American workingman. It’s obligatory for those in academe and politics today to virtue signal by condemning the Chinese Exclusion Act, but I suspect few of them have ever read its text or studied the effects of Chinese immigrant labor on the workingmen of California during the latter half of the 19th century.

Image Credit:

above: Workingmen’s Party rally at the sand lots near the old City Hall in San Francisco in 1877 (Library of Congress)

Leave a Reply