A boyhood pastime when I was growing up was building radios. We did it in Cub Scouts and again, at a more sophisticated level, in Boy Scouts. Various kits were available, but we all started with a simple crystal set. It seemed almost magical that with a few components, essentially wire and a crystal, and no power source, you could receive radio transmissions. We moved on to a more complex kit that utilized the power of batteries or an electrical outlet to amplify sound. I also quickly learned that the more antennas, the better. I strung wire antennas all over our roof. By the time I was 12 I had built a multiband radio that enabled me to tune in to transmissions from all sorts of sources. At night I’d listen to pilots, HAMs, and radio stations from distant towns. It was an adventure.

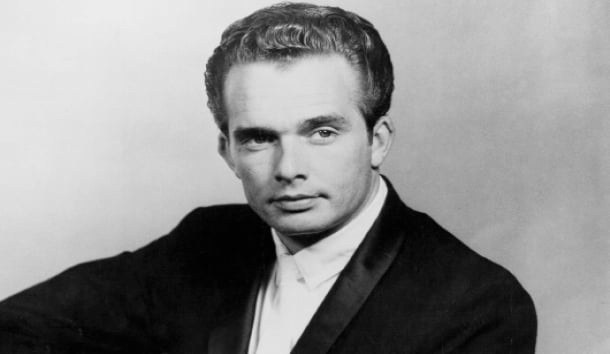

One of the stations I pulled in at night played what was then termed Country & Western. By the early 60’s I was regularly hearing a singer from Bakersfield named Buck Owens. While Nashville was generally recording a less raw and more mellow country sound in an attempt to broaden the appeal of the genre, Owens cut records in a Bakersfield studio that harkened back to the rockabilly sound that helped give birth to rock ’n’ roll.

Early in 1963 I heard what would become a chart-topping hit for Owens, “Act Naturally.” A Johnny Russell composition, it featured great harmonizing by Owens and his lead guitarist, Don Rich, a driving rockabilly drumbeat, twangy guitar riffs, and pure, raw emotion. I was knocked out. The next day in school—I was then a junior at Palisades High—I told several friends about this new Buck Owens song that they had to hear. The general reaction was, “You talking about that Okie from Bakersfield again?” Owens was actually born in Texas and grew up in both Texas and Arizona. Yet in those days in California, all the Dust Bowl migrants, whether from Oklahoma, Texas, Missouri, or Arkansas, were called Okies.

A couple of months later, Owens had another chart-topping hit, “Love’s Gonna Live Here.” Once more, I was knocked out, and again around school it was thought “uncool” to like the hick sound. The song and the music had all the ingredients of Owens’s earlier hit. In time the style would be called the Bakersfield Sound.

There was another singer and musician in Bakersfield who, while not yet recording hits, was causing a stir at the local honky-tonks such as The Blackboard, High Pockets, and The Lucky Spot. A good judge of talent, and seeing the crowds the newcomer was drawing, Owens asked him if he would tour with Owens’s band. The newcomer was a local boy. His parents were Okies. His name was Merle Haggard.

Merle Ronald Haggard was born in 1937 in Bakersfield to James Francis and Flossie Mae, who had left their farm near Checotah, Oklahoma, in 1935. Merle was the caboose of the family. His older brother, Lowell, was already a teenager, and his sister, Lillian, nearly so. The Haggards had struggled with falling prices for farm commodities during the 1920’s and 30’s. Then, in 1935, their barn was struck by lightning, and the structure and all its contents went up in flames. Jim Haggard called it quits, packed up the family, and took Route 66 to California, where tens of thousands of Okies had already fled.

Jim Haggard was fortunate to find work with the Santa Fe Railroad and settled in Oildale, a small, unincorporated community on the north side of Bakersfield. Oildale comes by its name honestly. On its east side is the Kern River Oil Field, with the second-greatest number of active oil wells in California, and to the north is the nearly equally large and productive Kern Front Oil Field. To the southwest is the Fruitvale Oil Field. The lucky ones in Oildale worked for the railroad or in the oil fields or maybe in a machine shop. Others, including children, found work as farm laborers. Merle Haggard was fond of saying he picked cotton long before he picked guitar.

The Haggards’ family home was a converted Santa Fe Railroad refrigeration car (usually referred to in stories about Haggard as a boxcar), set down on land that Jim Haggard later bought. In time he added amenities to the Santa Fe reefer—a bathroom, a kitchen, and a second bedroom.

Haggard grew up watching and listening to trains pass his home—the tracks were a mere hundred yards away. He also grew up listening to music on the radio and to his parents’ Jimmie Rodgers records. There was musical talent in the Haggard family. His father could saw a fiddle in two. Haggard would learn to play the fiddle and the guitar and took to both naturally. He loved to spent time with his dad and was devastated when Jim died of a cerebral hemorrhage when Merle was nine years old.

Haggard first ran away from home two years later. He and a buddy hopped a freight train in Oildale and, unable to find an open boxcar, hung onto the iron framework of a hopper car. They were nearly frozen by the time the trained pulled into the yard at Fresno shortly after midnight. A railroad detective soon had them in hand. Haggard thought he would be taken to jail and was intent on playing the tough kid. However, the railroad dick called Haggard’s mother, and she drove up to Fresno to retrieve the boys. She couldn’t understand why he had hopped the freight train when he could have used his railroad pass, a benefit he would enjoy until the age of 18 because of his father. Haggard tried to explain he had to hop a freight train and ride in a boxcar because that’s what Jimmie Rodgers sang about.

Three years later, he ran away again—with two girls. He somehow convinced them that they all should hop a freight train to Las Vegas, and he’d win plenty of money gambling to finance a grand old time. He spent hours trying to teach them how to hop a moving train, but finally gave up. Instead, he sneaked them onto a lumber car of a train still stopped in the yard. But they didn’t know where the train was headed. Well into the night, they found themselves in a rail yard in Los Angeles.

They managed to get out of the yard without a railroad dick descending upon them and, tired and cold, decided they should return home. Haggard spied a car. His criminal career was about to begin. He popped the hood, quickly hot-wired the vehicle, and off they all went. Five miles later the car ran out of gas. This was the first of Haggard’s many failures as a criminal.

They began to walk. They had 110 miles to go. Fortunately for them, they had actually gone several miles before a cop drove by and did a double take at three 14-year-old kids walking down the road at 2 a.m. He had no idea about the stolen car and took them to the police station to call their parents. Haggard played the tough guy and refused to divulge his name, but the girls readily gave theirs, and the parents were called.

Soon Haggard was off again, hopping freight trains and hitchhiking with a buddy to and from Texas. Upon their return to California they were mistaken for the perpetrators of a crime and spent five days in jail before the real culprits were arrested. Once back home, Haggard returned to school, but after two weeks he was gone again, this time to Modesto, where he worked in a hayfield by day and played guitar in a honky-tonk by night. At the end of the hay season he returned home, but not to school. A truant officer took him to juvenile hall. He escaped. He stole cars. He was captured. This became a pattern. Shortly before his 15th birthday, he was sentenced to 18 months in the California Youth Authority.

He suffered harsh and occasionally brutal treatment at the hands of the guards. He also quickly learned that the incarcerated Mexican and black kids had their own gangs. The white kids did not. This meant he had to fight for his life without the protection of numbers. He failed in four escape attempts, but a fifth one from a work party outside the CYA facility was successful for a time. But then he actually turned himself in to a highway patrolman; vigilantes were searching the area Haggard was in for a rapist and murderer, and he didn’t want them to mistake him for the miscreant.

Haggard was transferred to a higher-security facility and promptly escaped, but was later captured. He finally completed his sentence, and it was back to hopping freights, running off with girls, playing in honky-tonks, working in the oil fields, stealing cars, and being arrested. He spent nine months in the Ventura County jail. Once out, the cycle was repeated, and back to jail again. However, this time he escaped. Then it was life on the lam, until a botched robbery attempt when drunk sent him to San Quentin. When he appeared on NBC’s Johnny Cash Show in 1968, Haggard mentioned Cash’s concert in the prison in 1959.

“That’s funny, Merle, I don’t remember you being on that show,” said Cash.

“I wasn’t, John. I was in the audience,” replied Haggard.

I first heard Haggard in 1963 and ’64 on that same Country & Western radio station I picked up at night. He had three recordings that charted in those years, but it was the third one, “(My Friends Are Gonna Be) Strangers” that got me hooked on Hag. What followed through the 60’s and into the early 70’s was some of the greatest work ever done by a country artist—or by anybody, for that matter. For a short time he had his own nightclub in the San Fernando Valley—Hag’s Place. My brother and I and our wives were there for opening night in 1974. All I can say is, you should have been there.

Leave a Reply