Elvis

Directed by Baz Luhrmann ◆ Written by Baz Luhrmann, Sam Bromell, and Craig Pearce ◆ Produced and distributed by Warner Bros.

The first thing to be said about Elvis is that it’s been directed by the montage-mad Baz Luhrmann. I suppose Luhrmann thought his rapid-fire cutting of Presley’s story back and forth in time would impart the frenzied kaleidoscope of his rise to and fall from fame. Unfortunately, it also renders his story barely comprehensible. There are many points in the film where one is hard-pressed to say where or when events are taking place. Or, for that matter, who the figures in Presley’s life are.

Since Luhrmann decided to divide his focus on both Presley and his shady manager, the so-called Colonel Parker (who is played very well by Tom Hanks) the cutting does make some sense. Nevertheless, it renders the film irritating and incoherent. We start out with juxtaposed scenes of Presley at a black church where the congregation is singing lively gospel music and at a roadhouse where the customers are singing and dancing to “race music”—as it was called before being renamed rhythm and blues so that it could be played to white as well as to black audiences.

Young Presley, who lives in a black town outside Memphis, enthusiastically imitates the R&B performances for his friends. The noise and animation of the style inspires Presley’s singing and guitar playing. As he grows in fame, he also attracts not only young fans, principally women, but also captious critics such as Mississippi Senator James Eastland, who rails against Presley for imitating black musicians and injecting unseemly sexual allure into his performances with his infamous hip wiggling.

I recall first hearing Presley in 1955 singing “Heartbreak Hotel.” More imprinted on my memory was his rendition of “Hound Dog.” What I didn’t know was that this song was meant to be a black woman’s complaint against her neglectful partner. In the lyrics she berates him, “You ain’t never caught a rabbit / and you ain’t no friend of mine.” Had Presley articulated these lyrics clearly, I don’t think I’d have been as impressed. And if I had known he was singing the words spoken by an angry woman, I would have been confused. But my friends and I didn’t know this. We were responding to a loudly sung, infectious melody driven by a heavily rhythmic beat.

My cousins and I were so taken with “Hound Dog” that we played it on an overpowered jukebox at the concession stand on Tobay Beach, Long Island. To our delight, the sound reached halfway across the sand to the waves. This did not appeal to the beach’s other visitors, some of whom complained to the folks running the concession stand. Looking back, I can’t blame them. The volume was shattering. Presley was doing what rock-and-roll music is supposed to do: annoy adults. I’m not sure that was his intention, though, as he seems to have been something of mama’s boy.

Luhrmann’s Elvis asks us to adulate Presley. I’m fully ready to admire his talent, but I nevertheless deplore his excesses, which included a massive amount of drug use and womanizing. It’s the old story: too much, too soon. Luhrmann doesn’t show us much of this dissolute Presley, other than glancing scenes of his drug stash and mild flirtations with starlets. Presley reminds me of a scenario in Aldous Huxley’s novel Crome Yellow, in which a character is given enormous power and unlimited wealth in order to see where his unbounded inclinations lead him.

The film visualizes Presley’s temptation in Christian terms. At a carnival, Parker invites Presley to ride on a Ferris wheel. When the wheel lifts them to its highest point, Parker urges Presley to survey the ground below and asks him if he’s ready to fly. Presley hesitates a moment and answers in the affirmative. The scene echoes Matthew’s gospel, in which Satan takes Jesus to the highest point of the temple in Jerusalem and asks him to prove his greatness by throwing himself down. “Away from me, Satan!” Jesus curtly reprimands the father of lies.

This temptation scene has a more proximate source in Carol Reed’s 1949 film noir, The Third Man, when Orson Welles, playing the roguish criminal Harry Lime, takes his innocent friend Holly Martins (played by Joseph Cotten) on a Viennese Ferris wheel and asks him to join Lime’s murderous penicillin racket. Martins rejects the offer by asking Lime if he’s seen any of his victims. Lime points to the dot-sized humans on the ground below and asks Martins how many he could spare at $20,000 a piece. Martins has just enough character to counter Lime with his own question concerning the infants who have suffered, many mortally, from having been treated with the criminally diluted penicillin.

Presley lacks such character. Indeed, what 20-year-old rising rock-and-roll star would have been able to foresee the dangers lurking in the colonel’s proposal?

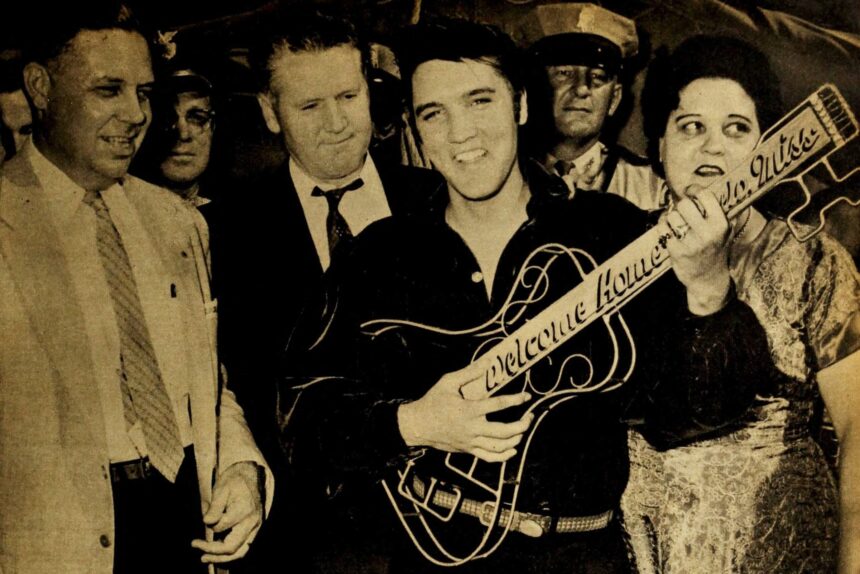

Image: Elvis Presley being given a guitar-shaped key to the city by Mayor James L. Ballard, in Tupelo, Mississippi, 1957 (via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Leave a Reply