Returning to the embrace of the Eternal City is never difficult. Its many charms make one easily forget the minor inconveniences: the strikes, noise pollution, and general chaos. The city’s many glories, both pagan and Christian, are always on display, easily accessible, even to the most unsophisticated of visitors.

Over the past decade, my wife and I have visited Rome regularly, on our way to see relatives south of the city—part of my ongoing effort to rediscover my father’s Italian roots. In fact, we’ve come to know certain areas of Rome so well that we can now suggest with some confidence where the best amatriciana is served west of the Tiber, or which church has the most intimate side chapel for a quick visit to the Blessed Sacrament.

A recent trip to Rome before the start of Advent led to the almost requisite walk across St. Peter’s Square. I never tire of seeing the seat of the universal Church. This time, with the results of the U.S. presidential election in mind, I found myself deep in thought. And as I looked across the square toward the side colonnades, I recalled a small conference I had attended in Vatican City two years earlier.

The theme of that conference had been “Poverty and the Common Good.” Organized by the Rome-based Dignitatis Humanae Institute (DHI), the conference was held in the Casina Pio IV, a 16th-century villa built in the middle of the Vatican Gardens, now housing the Pontifical Academy of Sciences and the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences.

The two-day conference brought together a small group of business executives and political officials, Vatican dignitaries (like Giovanni Battista Cardinal Re, prefect emeritus of the Congregation for Bishops, and Raymond Leo Cardinal Burke, patron of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta), and civil-society leaders from Europe and abroad. Discussions ranged from the role of markets to the role of morality in economic exchange, and guests participated in a wide range of presentations on reducing poverty, creating wealth, and the role of the state in the economy.

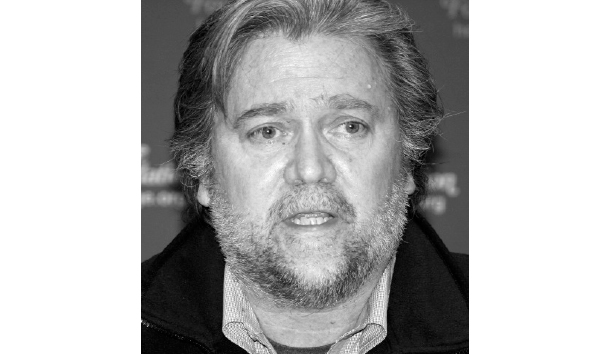

One conference participant stood out: Steve Bannon, who led the last session of the conference, speaking via Skype from California and answering questions from the audience.

At the time, Bannon was executive chairman of Breitbart News. He already enjoyed some notoriety, and his name made many American liberals shudder. Of course, now that he has been tapped as President-Elect Donald Trump’s chief strategist and senior counselor, everything has been grotesquely magnified—both his possible faults and the rage of the Democrats and the progressive left, for whom Bannon has become a lightning rod.

The reasons given for Bannon’s “unsuitability” for a White House role have ranged from the tired to the slanderous and libelous: He has been labeled antisemitic, fascist, racist, and misogynist. But I’ve been unable to reconcile what his critics are saying with what I heard that afternoon in Vatican City. In fact, the more I reread the transcript of the entire Bannon session (made available in the weeks after the election), the more he comes across as reasonable—and having a firm understanding that we are all called to be guardians of civilization and preservers of the Western Tradition.

Bannon continually praised a decentralized, common-sense approach to politics, both in the United States and abroad. This is precisely what is fueling the rise of many of the so-called populist and Euro skeptic political movements in Austria, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and the U.K. Bannon spoke with sympathy for the “global reaction against centralized government.” He also expressed his disdain for the world’s bean-counters, corrupt elites, and overzealous regulators, and seemed to share a faith in the accumulated wisdom of traditional families, hard-working communities, small towns, and sovereign states.

During the conference, Bannon—prompted first by DHI founder and president Benjamin Harnwell, and later responding to audience questions—spoke eloquently about some of the challenges currently facing the world. He noted the problems that secularization has wrought across human societies and in economic relationships, and pointed to the need to defend our civilizational ideals. Speaking to the conference’s main theme, Bannon highlighted the critical links between freedom and the “entrepreneurial spirit” and the process of wealth creation and poverty alleviation.

One particularly interesting moment concerned Bannon’s efforts to distinguish between two “disturbing strands” of capitalism: the “state-sponsored capitalism” of China and Russia, which limits man’s economic freedom and individual liberty, and the “objectivist school of libertarian capitalism,” which denies basic human dignity by reducing man to an object or a commodity. On this, Bannon was impressive. No ideologue here, I thought.

In his responses to questions from conference participants, Bannon made other important points. He mentioned the broad denial of our Judeo-Christian heritage, both in our culture and in our institutions of government, in America and throughout the West, and he spoke with gravity of the growing threat of “jihadist Islamic fascism.” He also noted the growing frustrations of middle- and working-class people worldwide who, through political movements like the Tea Party in America and the U.K. Independence Party, are finally beginning to challenge the power of the world’s political and economic elites in places such as Washington, Brussels, and Beijing.

I had a brief opportunity that afternoon to ask Bannon a question. Taking a cue from his comments about populist movements in Europe, I asked about the growing “Identitarian” movement that continues to spread on the fringes of the European right—in France, Austria, and Sweden. Animated by a total rejection of immigration and a return to a kind of “ethnonationalism,” these Identitarians also reject market capitalism, globalization, and free trade, and—more troubling—espouse a return to discredited statist economic policies. My question raised these points and asked what we could do to counter the appeal of Identitarian movements to young people.

Bannon pointed out that because of crony capitalism, and the use of “a different set of rules for the people who make the rules,” many of the people expressing support for the Identitarian and “neonativist” movements were simply not seeing the benefits of market-based capitalism. Solve this, and you will see benefits flow back to people, he said. Later on, in response to a question from a Slovakian journalist, he suggested that antisemitic and racial elements are always found on the “fringe” of populist movements, but that they will “burn away over time and you’ll see more of a mainstream center-right populist movement.”

The reason for my question was the work many of us have been doing in Europe over the past decade. European conservatives—in the Netherlands, Sweden, and Croatia—have been contributing to efforts not only to educate others about important conservative ideas so that someday a critical mass may be reached but also to influence public policy at the national and European levels. They seek to preserve and promote the good that still remains in fragments across Europe.

Part of this laborious and ongoing effort has involved the task of definition—that is, the job of distinguishing what is soundly derived from established principles from what is merely an innovation—in order to forge a truly respectable conservatism. In other words, the conservatism that many in Europe seek is one that distinguishes itself clearly from any of the neopagan and fascist modes of right-wing thought.

The Identitarian movement is just the latest iteration of this kind of deformed protofascist thinking, which Identitarians see as flowing from, say, Asgard, pulsing through the blood of the Volk, and reaching down into the ageless soil. This kind of thinking is not only unpalatable (especially to ethnic types like me) but potentially dangerous, as it tends to seek solutions from the state and calls for increased government intervention to solve problems—which inevitably seem to hinge on race.

We are, of course, seeing a similar phenomenon emerge in the U.S. now. The Alt-Right, which one could argue began with some reputable ideas that could have found common ground with the grassroots ideas of the Tea Party, very quickly descended into the crudest kind of racialism.

This is not the sort of conservatism that the world needs. Rather, the challenges of today, as Bannon suggested, require a response that is firmly based on the classical Judeo-Christian principles that we have inherited from Western civilization. These principles are not tied up with the clan or the Volk. They are the product of the Tigris- Euphrates River Valley, from which Western civilization flows.

I have no doubt that Bannon understands all of this. His comments during the conference demonstrated an impressive understanding of history, as well as knowledge of philosophy and economics, and a firm grasp of the complex global problems we are facing. In stark contrast to the way the media and his left-wing critics have recently portrayed him, he moved easily in and out of different complex ideas, and brought to bear insights from numerous disciplines. In short, he demonstrated a willingness to engage in conversation about matters of grave importance.

Bannon’s appearance at that 2014 conference was rather unexpected. In retrospect, however, it clearly demonstrated the astute, even prescient thinking of DHI’s founder, Ben Harnwell, who successfully brought together a range of committed and morally courageous people who shared similar concerns about the direction of the world.

As I walked back down Via della Conciliazione that evening, and across the Ponte Vittorio Emanuele II, reflecting on Bannon’s comments at the conference, it struck me that he could very well end up being President Trump’s best asset, his greatest ally and most intelligent advisor—a modern Sir Thomas More without the gory end. Perhaps that’s an encouraging enough thought to give us all hope.

Leave a Reply