The bitter war of words that has taken place the best part of this past year between France and Italy culminated in the French government taking the extraordinary step of withdrawing its ambassador to Rome in February.

On one level, this drôle de guerre is between two governments which hold dramatically different views of the European Union. In other words, it is a war between the Europhile liberal-elitist French government and the Euroskeptic populist Italian government.

It encapsulates the existential struggle at the heart of Europe between two competing visions that will dominate the forthcoming European Parliament elections in May: that of Europe’s imperialisti and their standard-bearer, French President Emmanuel Macron, who want ever closer union; and that of its sovranisti, championed by Italy’s populists, who want a return to a Europe des Patries, as General Charles de Gaulle defined what the E.U. should be. According to this view, it is not a war between the French and the Italians as peoples but only between their governments.

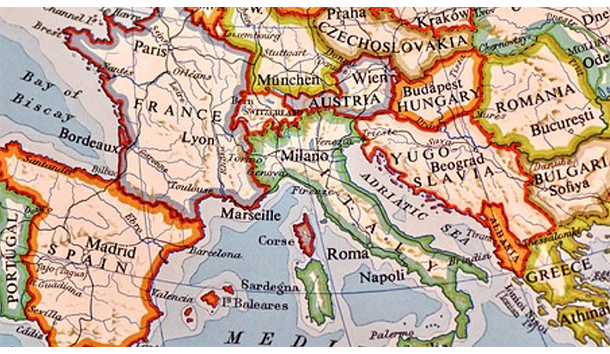

But the European Union, regardless of Brexit, is in crisis precisely because it is made up of peoples—peoples who do not even speak the same language. The only thing they have in common is not even democracy but Christianity. Yet the E.U. refused to incorporate such old-fashioned and irrelevant stuff in its founding document: the Treaty of Lisbon (2007).

All know that the only way to make the E.U. work is to make the single currency work, and yet the only way to make the single currency work is political union.

And yet, as everyone also knows, few people in any European country want political union because few people feel European—least of all the Germans, as union would require them to accept joint liability for the massive sovereign debt of certain Mediterranean countries. Instead, all feel French, or Italian, or whatever.

Political union in the E.U. could only ever be achieved, therefore, if imposed against the will of the people of Europe.

But on a deeper level I am convinced that this war of words between the French and the Italians is not just between their governments but between their peoples. To concede that there are differences between the French and the Italians, or between the citizens of any nation, is virtually verboten these days. To “stereotype” national differences is almost as toxic as talking about the differences between men and women.

Let us not forget: The nation-state is the Devil Incarnate as far as the unholy alliance of global capitalists of the right and global liberals of the left is concerned. To the former, it is an obstacle to profit; to the latter, the root of all evil.

Given the takeover by this left-right global alliance of the vital organs of Western culture (which reminds me of the short-lived alliance between Nazi Germany and communist Russia in 1939), it is hardly surprising that the media coverage of the shouting match between the French and Italian governments has been a classic example of fake news. The stock phrase in all the reporting is “after months of provocation by Rome.” The real explanation, though, is pretty obvious. Macron, an ex-merchant banker at Rothschild and minister in the last Socialist government, married to a woman old enough to be his mother with whom he has no children, is the perfect darling of the liberal elite. He is perhaps their last hope in Europe. As a result, the French are endlessly described by the media as the reasonable and right victims of the nasty and hysterical populist Italians.

What bullshit.

Yet this was the constant media refrain when Macron decided to withdraw his ambassador to Rome, which was the first time a French government had done such a thing—it was quickly pointed out—since June 1940 when the fascist dictator Benito Mussolini declared war on France. This comparison had the added advantage of equating Italy’s populists of today with Italy’s fascists of yesterday, and thus fit nicely into the bigger narrative that populism is the fascist phoenix risen from the ashes.

But it is Macron and the French who have been the agents provocateurs here. It is the French who lashed out in spades from the word go at the first-ever populist government in a major E.U. country, Italy, since it was formed last June.

The pretext for withdrawing the French ambassador was a visit to France by the Alt-Left Five Star leader and Deputy Premier Luigi Di Maio during which he met leaders of the French gilets jaunes (yellow vests) populist revolt that has done immense damage to the Macron presidency. Let us be clear: The gilets jaunes have wreaked havoc across France, but they are a spontaneous protest movement and not a banned terrorist organization such as ISIS, or even the IRA. So what’s the big deal? Apparently, Di Maio’s visit came after “repeated baseless attacks,” according to the French Foreign Office, and “violated the most elementary diplomacy” because it was “unannounced”—i.e., he did not inform them he was visiting.

Oh, come off it! Is that the best Macron can do?

Last summer, when Italy’s other deputy premier, Matteo Salvini, leader of the radical-right Lega, banned NGO “rescue” ships from dumping illegal migrants picked up off Libya in Italy (so causing the global liberal elite to hyperventilate with outrage), Macron described the ban as “irresponsible” and “cynical” and got one of his aides to call it “nauseating.” Yet—quelle surprise—he then regularly refused to allow NGO ships turned away by Italy to dump their migrants in France.

Meanwhile, as Salvini was quick to point out, Macron ordered the French police to send back to Italy migrants caught crossing the Italian frontier with France on the Riviera, in contravention of the E.U.’s sacred principle of free movement. Since the start of 2017 the French have sent back a total of 60,000 migrants.

Salvini wants to stop the migrant flow from Africa, and if he cannot do that he wants the migrants to be shared across Europe. Macron, on the other hand, despite all his virtue signaling, like everyone else in the E.U., refuses to play ball. It is Italy’s problem, they all say. But Italy has already taken in 650,000 illegal boat people since 2014—nearly all men of fighting age from sub-Saharan Africa and the majority of whom, as even the U.N. admits, are not refugees. And Salvini’s incredibly popular message with Italian voters is: Basta!

Macron has defined populism such as Italy’s as “like leprosy.” Yet Salvini rides ever higher in the polls, and Macron ever lower. The French president should perhaps ask himself why people prefer leprosy to him.

There is now a bit of a truce, and the French ambassador is back in Rome, but hostilities are sure to recommence as the E.U. gears up for the European Parliament elections, which appear set to give populists enough seats to play a truly decisive role for the first time ever.

It may be toxic to say so, but I do not care: There are differences between the peoples of different nations—despite the relentless march of globalism.

I lived in France for a couple of years before coming to live in Italy 20 years ago. And I have no conflict of interest. Au contraire. As I know to my cost, Italy is a great place to visit but a nightmare to live and work in. I know all about stab-in-the-back Italians and fiddling everything under the sun. I understand exactly why then-U.S. Ambassador John Phillips told Italian businessmen a few years ago that the reason American entrepreneurs invest more in tiny Belgium than in the world’s sixth largest economy is the inability to enforce a contract in Italy, largely thanks to her sclerotic legal system.

Naturally, I refuse to become an Italian even though I could. I do not feel Italian and never will—even though with my Italian wife I have six children who are. But nor do I feel European. Who does? I am an exile.

And yet I still love the Italians because love without despair and hatred is not love. I prefer them to the robotic Germans (who doesn’t?) and increasingly, too, even to the smug-as-shit British. But above all, I prefer them to the bloody French.

The Italians are just far less uptight, arrogant, condescending—and negative. And they are far more fun. They are more human. The French may be technically and legally right on all sorts of things, but the Italians are emotionally right. And that, these days, is priceless.

Above all, I love the Italians because what counts in life is passion, and they are passionate.

And passion is both chiaro and scuro. It is extreme light and dark, extreme love and hate, extreme happiness and unhappiness, extreme emotion—one way or the other.

Yes, Italy is a byword for dishonesty and deceit and—mamma mia!—after two decades here I know all about how that pans out.

But guess what? I would trust an Italian more than I would a Frenchman.

I’ll go further. I would rather be in a First World War trench with an Italian than with a Frenchman as we go over the top and die.

When I left France all those years ago, I cannot tell you the life-enhancing difference I felt as soon as I crossed the frontier in my metallic burgundy Honda Prelude.

On arrival at the Italian motorway toll-gate that stifling summer of 1998, I did not have any money to pay the toll, and the intense sun had melted my bank card, which I had left on the dashboard. But the charming young woman manning the toll-gate gave me a form to fill out and waved me through with a devastating smile. Isn’t this how we should run the world?

The French, on the other hand, given even half a chance, take a sadistic pleasure in denying people a solution.

You may think I am nuts, but I am not alone. The great 19th-century French novelist Stendhal despised the French but adored the Italians and spent much of his adult life in Italy trying to explain why. With the exception of Napoleon, in whose army he had served and whom he idolized, Stendhal felt that the French were frigid, sterile, bigoted, artificial, insincere, money-grubbing, and vulgar. This was because, he thought, they had lost passion. They could not feel genuine emotion anymore.

The French “never sin out of love or hate,” he wrote, but only for personal gain, whereas the Italians are frank, natural, and honest, and thus sincerely passionate, as are the sins they commit. The Italians are ruled by their emotions even if to the point of madness.

And this is how Vittorio Feltri, editor of the Milan daily Libero and barometer of popular Italian sentiment, put it: The French “invented the bidet, but do not use it.” As for Macron, “one who has been sleeping with his grandmother for decades,” Feltri asks, “is he allowed to insult the rest of us who, with their champagne, rinse our ass?”

I could not possibly imagine a famous French columnist ever saying such a thing—not even about the Italians.

Vive la différence! And Evviva l’Italia!

Leave a Reply