It was nearly dusk on September 7, when we arrived at the outskirts of Tal Afar, Iraq. On the main highway to Mosul, about a dozen Iraqi policemen at a checkpoint were supervising a frightened exodus of civilian refugees. For the past week, there had been media reports of escalating violence between resistance fighters and U.S. troops in Tal Afar, and already many of the residents had fled the embattled city. From American services in the Mosul Airfield, I had learned earlier that day that a major U.S. offensive was about to begin. The Americans had reinforced their local garrison with an additional battalion of armor and infantry, and I was advised that, within days, the U.S. military was going to “clean house” in Tal Afar.

I intended to enter the city before it was shut down and then send reports about the civilian casualties and possible humanitarian crisis that would result from a major battle. I knew there would be some risk involved—particularly once the Americans attacked—but I planned to observe the fighting from a safe house, well away from any actual combat.

The sight of U.S.-paid Iraqi police forces monitoring traffic had seemed like a good sign that things were still under control, despite the recent fighting. As I did not have an exact address for my previous contact, I approached a police checkpoint to ask for assistance. When I asked to be taken “to Doctor Yashar,” they recognized his name as a prominent local Turkmen official and eagerly nodded in the affirmative. A senior policeman was summoned, and he instructed me and Zeynep Tugrul, a Turkish journalist who was serving as my translator, to climb into a nearby car containing four masked gunman. As we clambered into the backseat, one of the gunmen said, in excellent English, “We will take you to Doctor Yashar—please, do not be afraid.”

I had presumed that these men were some sort of special police force—our own Canadian counterterrorist teams often wear ski masks—so I had no immediate cause for concern. However, as soon as we entered Tal Afar, I saw that the streets were full of similarly masked resistance fighters armed with Kalashnikov rifles and rocket-propelled grenades (RPG’s). I suddenly realized that we were in the hands of the resistance. We were ushered into a small courtyard outside a walled two-story building housing about a half-dozen armed men.

As soon as the metal door clanged shut behind us, the English-speaking leader said, “You are spies, and now you are prisoners.” All of our cameras, equipment, and identification were confiscated, and we were told to sit on a mat with our backs to the wall. “The Americans will attack soon, and I have to see to my men,” said our captor. “I will deal with you when I return.”

Shortly after nightfall, they brought a platter of food into the compound, and, in what would soon become a routine pattern, they served us first before eating dinner themselves. I did not have much of an appetite.

The plates had just been cleared away when another car pulled up outside and four new gunmen came quickly through the door. Before I could even react, I was pulled to my feet and pressed against the wall with my hands on top of my head. Almost immediately, I heard the distinct sound of a Kalashnikov being cocked about a meter behind me. In fear and shock at the realization that they were about to execute me, Zeynep screamed in Turkish: “Don’t shoot him—he has a son!”

The outburst was enough to distract them momentarily, and they began to explain to her the necessity of killing a “Jewish spy.” Thankfully, I had no idea what was being said. The brief discussion was still taking place when our original captor returned. Harsh words were exchanged between the two groups of gunmen, and it seemed as though a prisoner’s fate was the proprietorship of those who made the capture: The would-be executioners left.

About two hours later, I was blindfolded and roughly manhandled into what felt to be an SUV. At the second house, I was rushed through several doorways and up several stairs. With my hands tied behind my back and unable to see, I stumbled and fell several times, only to be pulled brusquely back to my feet and once again shoved forward. “Hurry, hurry, you bastard Jew,” whispered one of my guards as he slammed my head into a door frame.

I was forced to lie facedown on a mat, and two men carefully searched through my pockets. Finding my money inside my sock (about $700), they laughed and said, “Your money is our money—you won’t need cash in heaven.”

It was difficult to gauge how long I laid there in the dark, but my shoulders were aching when they finally untied my hands and brought me to another room for interrogation. My blindfold was removed, and they shone a bright flashlight directly in my eyes. “Which intelligence agency are you working for?” For about one hour, I did my best to explain to them that I was a journalist. Two men were questioning me. In what seemed like a bad Hollywood comedy, someone fired up a generator outside, the lights came on, and the two interrogators clumsily tried to pull their ski masks back on before I could recognize their faces.

With the tension broken, the one who had identified himself as “emir” (leader) actually started to laugh and left his mask off. This man had been among the group that had taken us at the police checkpoint. “Sleep now, and I will check your story. If you are telling the truth, we will release you; if not, you die.”

I was kicked awake the following morning, rolled onto my stomach, blindfolded, and bound. They transported Zeynep and me to a the third house, where our blindfolds were removed, and we were fed a generous breakfast of fried eggs and flat bread. After a cup of tea, I was escorted to a small room with barred windows. Two middle-aged men and a 15-year-old boy, who stated that his only ambition in life was to “die a martyr,” stood guard. They were obviously not frontline mujahideen, but they still supported the resistance.

Shortly past dark, the emir returned and informed us that he had confirmed that we were not spies. He gave a “Muslim promise” to set us free in the morning. On this night, Zeynep and I would remain his “guests.” We were also about to become front-row spectators to an intense battle between the resistance and U.S. forces.

Just past midnight, the American Apa-che helicopters attacked. Their arrival over Tal Afar was greeted by a heavy barrage of RPG and cannon fire. From inside the workshop’s courtyard, we could not see the battle’s progress, but, from the sounds of the gunfire, we could plot its course. On several occasions, the mujahideen all across the city screamed, “Allahu akbar! Allahu akbar!” (“God is great!”) I had first thought that these cries were in response to the downing of a helicopter, but our young guard explained that they were cheering the deaths of their own, newly created martyrs.

At about 3 A.M., there was a loud banging on the courtyard gate. Our guards let a resistance fighter inside, and he spoke quickly with them in Turkish. Hurriedly, a storeroom was opened, and the fighter helped himself to three RPG’s, which he tucked inside his belt. I could see inside the small room, which was literally packed with munitions, and I realized that we were being held captive in one of the resistance’s ammo depots. The fighter took a bowl of water, drank thirstily, then rushed back out onto the darkened streets. Minutes later, he began firing from a rooftop about 50 meters away. He had only managed to launch two of his rockets before he disappeared in a burst of 25 mm cannon fire from an Apache that literally blew him into pieces. Following a brief silence came the chorus of “Allahu Akbar!”

In the morning, Tal Afar was strangely quiet, except for the continuous buzzing of the unmanned Predators overhead. The Apaches were gone, and the resistance was licking its wounds. It was reported that 50 mujahideen had been killed and another 120 wounded. The worst news of all was that the emir had been killed, the target of a Predator missile that had successfully destroyed his Land Rover. While his followers celebrated his martyrdom, the emir’s death left a power vacuum among the mujahideen.

Around mid-morning, a group of gunmen arrived at the workshop to take us away. Zeynep pleaded with them in Turkish that we were to go free, but it was to no avail. “We received no such instruction,” said the man who now appeared to be in charge. “You are spies.”

This time, they were extremely rough in applying my blindfold. It was tied so tight that I could sense that I was losing blood circulation in my brain. They pushed and prodded me blindly toward a car and then deliberately bashed my head against the door frame. “Jewish pig!” spat one of the guards.

At the fourth house, which smelled like some sort of farm complex, I was once again rushed through doorways and then down into a cellar. In addition to the blindfold, they placed a hood over my head, and I felt I was suffocating in the heat and dust. I could feel the fear well up inside me as one of the gunmen forced me onto a mat and placed the barrel of a Kalashnikov against my neck. “Don’t speak. Don’t move.”

Another group of men entered the cellar and began questioning Zeynep as to our identity. She told them of the emir’s promise and advised them that our papers were all at the first house. Finally, we were allowed to remove the hoods while the mujahideen went to check out our story. At this point, I realized that there was another prisoner in the room with us. He was an Iraqi from Mosul—also accused of spying. He was not allowed to remove his hood.

Throughout the rest of the morning, there was plenty of activity in the resistance bunker. About 30 or so fighters were busy transferring stockpiles of RPG’s and explosives. In addition to the gruff male voices, we could hear an elderly woman shouting encouragement to the men. “They call her mother,” whispered Zeynep. “She is encouraging her ‘sons’ to go out and become martyrs and die in battle. Can you believe it?”

Our previous interrogator returned to our makeshift cell to advise us that our bags, cameras, and identity papers were now buried under a heap of rubble: The first house had been destroyed by a precision-guided bomb. With no proof of our nationality or profession, a heated debate among the fighters soon erupted outside in the corridor.

Listening to their conversation, Zeynep suddenly gasped: “O my God—they’re going to shoot us!” I fought to suppress the panic that I felt. It was then that the other prisoner spoke for the first time. In good English, he said, “Are you sure?”

The door burst open, and several men stepped inside. “Stand up,” one of them said to me. “You are the first to die, American pig.” My hands were still tied, and I felt helpless as one of them approached me with another blindfold. I told them that I did not want a blindfold—not out of any bravado, but because I found that the sense of fear was magnified by the inability to see. I received a punch on the head for my protest, and the blindfold was pulled snugly into place. This time, they added a gag and a black hood.

Once again, I could feel the claustrophobia and fear beginning to panic me, and I struggled to maintain some composure. The cries of fear and alarm from Zeynep had caught the attention of the woman, who apparently had not realized that the men were detaining a female. She entered our cell, and a heated discussion took place between her and the fighters. Several times during their conversation, I was struck, and I still believed I was about to die. Finally, one of the mujahideen came close to me and whispered, “I have a brother in Canada. I have just saved you, my friend—at least for now.”

They had decided to take us with them. The Americans were about to bomb their complex so they were going to leave Tal Afar until the air strikes were over. The hood and mask remained in place, and the man who said he had saved me warned me not to make any noise. “If my people hear someone speak English, they will beat you to death before I can stop them—now move!”

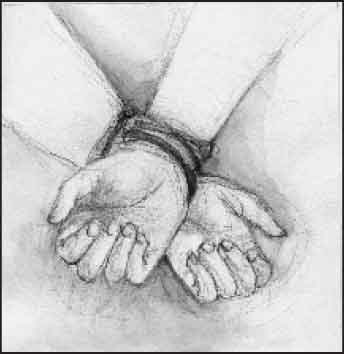

Although the Americans had claimed they had “sealed off” Tal Afar before launching their offensive, I soon learned that was nothing more than wishful thinking. We had left the bunker in a six-car convoy and made our way northward into the open desert. It had taken some time before the mujahideen had relented and allowed us to remove our hoods and blindfolds. Our hands were still tied, but I had sweat so much in the 45-degree (Celsius) heat that the moisture had loosened the straps. I was able to free my hands easily—and, in an effort to gain their trust, I had shown them that my bonds needed to be retied. The man next to me had simply laughed and instructed me to “forget about it.” After all, where can you go in the desert?

As we began chatting, this short gray-haired man with a close-cropped beard informed me that his brother was the now-deceased emir. “I’m sorry about his death,” I said, to which he replied, “Why be sorry? We celebrate his entry into heaven.”

What was reassuring to me was that, as the brother of the former leader, this man appeared to have filled the immediate leadership void in the group. I was especially relieved to learn that his brother had told him of the decision to set us free. We were also told that we had only to have our identities confirmed—via a Google search on the internet—and he would keep the promise of the martyred emir. In the meantime, we would remain with the mujahideen.

Around 2 P.M., we had stopped near a remote desert house. The nearly 30 fighters had assembled around our car and began to conduct a mass prayer. Zeynep and I were instructed to remain in the car. It was as they were engrossed in their prayer that I spotted the two American helicopters coming out of the south—low and fast and headed straight toward our parked convoy. I cried out in alarm. The mujahideen were angry at the interruption, until they, too, spotted the approaching threat. Caught out in the open, they were sitting ducks. Nobody could move; they simply watched the helicopters steadily bear down on us.

At about 800 meters, the gunships inexplicably banked away to the east without so much as a reconnaissance overpass of our mysterious group of vehicles in the middle of the desert. “They always fly the same patrol routes,” explained one of the fighters. “They see nothing.”

Shortly after the helicopters had departed, two additional cars joined us, and the mujahideen began hastily transferring the huge stockpiles of explosives and rockets into them. “We are making them into suicide bombs,” said Mubashir, the emir’s brother, of the cars being loaded and wired. “These men will head back into Tal Afar and use the vehicles to destroy the American armored vehicles.” A total of four mujahideen climbed into the suicide cars, and, as they drove back into the battle, their comrades shouted a final encouragement.

We proceeded on through the desert toward the northern outskirts of Mosul. Along the way, we stopped at several farmhouses where the residents eagerly offered the fighters food and water. When we actually entered the Mosul checkpoint, the Iraqi police appeared to take no notice of the dusty column of cars packed with bearded men armed with Kalashnikovs and RPG’s. A gauntlet of young boys lined the route to cheer our convoy and offer water and cigarettes. Instead of entering the city, however, we headed farther north to a deserted house that was still under construction. We were ordered inside the building, and I realized that the other hostage, a driver for UNICEF, had spent the entire three-hour desert transit in the trunk of one of the cars. He emerged from the vehicle, still blindfolded, covered in dust and sweat, and without his shoes. He was in terrible condition, but he made no sound of complaint as they hurried us into the empty house.

All but one of the cars soon departed, leaving only two armed guards with us, so the possibility of escape crossed my mind. It was the hottest part of the day, and the sentries were exhausted. Although it was open ground, the Mosul highway was clearly visible, about two kilometers away. With all the passing traffic, it would be possible to flag down a ride—if I could only survive the run.

Before I could give much thought to such a plan, another car pulled up at our hideout. Four new mujahideen strode into our building and immediately began berating the two guards for being lenient with us. The leader of this group was a short, stocky, little man who strutted about with his ski mask on. He wasted no time in making his thoughts known. “The Turkish girl will live. You two will die,” he said, pointing at me and the UNICEF driver. “I will cut off your heads at dusk, and you will be buried there,” pointing to a freshly dug grave-sized ditch about 20 meters from the house.

Zeynep was removed to another room and we were told to prepare ourselves to die. Although forbidden to talk whenever the guard was distracted, the driver and I took the opportunity to encourage each other. “At least we will not die alone,” he said.

Leave a Reply