On Monday, September 12, my friend and mentor died at the age of 82 from lung cancer after a decade of up-and-down health problems borne without complaint—a man whom I have loved more than any other man but my own father, starting from the time of our first meeting after I matriculated at Wabash College in 1996.

Last April he returned my call from a month or so before, apologizing for not getting back to me sooner: He had been taken to the hospital to undergo chemotherapy, he said, and was sorry for being out of touch. I saw him shortly thereafter on a visit to Crawfordsville, Indiana, and he was frail—diminished into a Hoosier hobbit—but as sharp as ever for a man who became a lawyer in midlife, taking night classes at his alma mater, Indiana University, while teaching at Wabash during the day. (After passing the bar he became deputy district prosecutor for the county in which Wabash is located, a job served in addition to his professorial duties. He once told me it significantly influenced his teaching. “When one deals with clients who are in trouble, one is compelled to look at all sides of what is involved in that particular case. The raw power that undergirds the legal justice system requires balanced judgment if it is to serve just ends. That same balanced judgment is equally desirable when teaching a course.”) Referring to ObamaCare, he declared, “They’re never going to lay their hands on me!” And when he said this he laughed, tossing back his head in such fine-spirited mirth that his hearty soul blazed forth like a thunderbolt through his faltering frame, several teeth missing in a weary-looking head that his wife and son told me suffered more than he ever let on. But that was the sort of man he was. Not one to complain. In short, a man.

He told me that he accepted the oncoming of death, if that short-term prognosis should be his fate; said in that Southern Indiana twang that, the first time I heard it, this Chicagoan mistook for an accent from deep below the Mason-Dixon. He thanked God for a good, long life untroubled by regrets, even though he had given up the Larks several years before being diagnosed with lung cancer. Ever hopeful, however, he was saying prayers to Saint Peregrine, patron saint of cancer patients, in case a quick fix were able to let him live longer with Maria, his wife of nearly five decades; his son, Ian; his daughter-in-law, Sharon; and his little granddaughter, Hannah. It was not to be, but they told me he suffered without complaint, barely able to speak in his last days but in complete control of his faculties, piercing Scottish blue eyes bright through his last day. The week or so before he died, his liberal niece paid him a visit. Barely able to speak, he beckoned her near and whispered in her ear, “Are you a Democrat?” He smiled and twinkled his eyes.

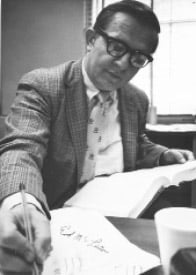

And so he laughed a final farewell to his politically misdirected niece, there from the hospital bed placed in his home. That house, built in the mid-1800’s and located a block from Wabash, served as a minicampus for students after he retired in 2003 after 35 years teaching political science at Wabash. Unlike the little college office where he would host students, speaking with gentle and perceptive words through strains of classical music and plumes of cigarette smoke that seemed always to discourage but never to kill the potted plant on his windowsill, Professor McLean would teach the young men in his civilizational parlor, surrounded by good books, where he hosted a G.K. Chesterton reading group and would mentor at least one of my friends into converting to the Catholic Faith.

I got the news of his death while walking down the street near the local community college, in the form of an e-mail from his son, Ian. “Dad died peacefully in his sleep the night before.” I read it on my BlackBerry that bright and sunny morning. And then I found myself bawling, wiping away tears and feeling embarrassed and weak. Prof. Edward B. McLean’s death pounded me like a sucker punch in the solar plexus of my soul. It seemed a disturbingly unkind reaction to the passing of a true Christian gentleman to what, in the Lord’s mercy, must be an eternity of rest, making this temporary sorrow of mine seem not only stupid but foolish. The accounting for emotions is a tricky business, however, but as Benjamin Franklin once wrote under the guise of Poor Richard, “Time is an herb that cures all diseases.”

I met Professor McLean my first week after matriculating at Wabash College. I had enrolled in the last minute, after putting all my eggs in one basket on the military route, and dropping that basket in December of my senior year of high school without making any thoughtful contingency plans: getting accepted to West Point on a senatorial nomination but being rejected as 4-F because of a weak left eye. Thanks to my dad’s research in The National Review College Guide: America’s Top 50 Liberal Arts Colleges, I discovered Wabash—one of two remaining liberal-arts colleges for men in the country—and, at his insistence, applied and got a solid scholarship. I also got a mentor in the person of Professor McLean, whom the guide suggested as a stalwart conservative. Every freshman had to take a tutorial—a class given by a professor out of love, even if beyond his discipline—and based on this recommendation, I decided to take his, the pot being sweetened by believing I had a call to the priesthood, albeit somewhere down the line. His class did not have the catchiest-sounding title—“The Social, Political, and Economic Teachings of the Catholic Church Through the Papal Encyclicals”—but it served as an introduction to the spiritual and intellectual life far more powerful than anything I could have expected at West Point, let alone one of several nominally Catholic colleges I’d been accepted at in the interim.

In three months I would learn more about the Catholic Faith than in the previous twelve years of Catholic schooling, my teacher having been all the more effective for being a late-life convert to Catholicism, which, as John Paul II explained in his encyclical Fides et ratio, is a faith that, appealing to one’s reason, justifies that final leap of faith.

Oh, but the first time I met him was at a dinner picnic with his tutorial students the week before the start of class. We were sitting at a picnic table, and he was wearing a seersucker suit (the first I had ever seen). He always seemed to be wearing a suit; until recent years, I had never seen him wear casual clothes. In fact, the last time I saw him, this past spring, a fellow alumnus and I visited him at home. Ringing the doorbell, we saw him walk within the hallway wearing long sleeves, take his jacket from the clothes tree, and straighten himself up in the mirror. “What class!” exclaimed my friend, a New Yorker for whom going to school in small-town Indiana was akin to studying abroad.

But that first night I met him in 1996, we were sitting at the picnic table. I told him that I came from Illinois and admired Abraham Lincoln. “Lincoln? That monster?” he countered, in slightly mock horror. “Thanks to him the Constitution has been defunct since 1861, and over half a million of his fellow Americans died as a result of it.” I was baffled. How could a conservative say this of Father Abraham? Over the course of taking his classes the next four years, however, I learned about Christian principles and constitutional thought, shattering some pop-con idols while raising up the statues of great men toppled by un-Christian and anticonstitutional victors, whether on the battlefields of the 19th century or within the classrooms and courts of the 20th. But what is an education for?

The things he taught me are so elemental that, in retrospect, they seem prosaic. But the dexterous presentation of the simplicity of truth, delivered by a man who, though gentle, was a man, affects me all the stronger now that I think of Professor McLean. Now, as I read through our correspondence and flip through papers with his copious marginalia, I am thinking back on times not so long ago when he succinctly presented me with plain truths that should guide me through life: the difference between freedom and license; that no man but a madman intentionally does evil; that faith and reason are complementary; that “there is a fine line between being a bad man and not being a good man” (something he observed at our last meeting, apropos what, I forget); and that, as he told me in an interview for the conservative magazine I edited, The Wabash Commentary, “I think God made a mistake when He didn’t limit every human being to one million words. People would be very judicious about what they would say.”

Professor McLean inspired both personally and through his writings, especially the collections of essays he edited for the Intercollegiate Studies Institute, which, like the books of his friends Russell Kirk, Ralph McInerny, and Marion Montgomery, remain in print and can serve to redeem the time, one mind at a time. At our last meeting, he said he was working on “a book and a novel about faith and practice.”

His funeral was simple and dignified. Professor McLean was laid out in the church before Mass. His hair was cropped short, attesting to the ravages of late-term cancer, but his countenance bore a look of peace amid the good will of the crowd of mourners, from his friends on the board of Liberty Fund to the president of Wabash College to the tight delegation of his immediate family. The day before the funeral, Ian, who followed in his father’s lawyerly footsteps and is an Indiana deputy attorney general, called to ask me to serve as the pallbearer representing Wabash because I was “so close to Dad.” And on that bright and sweet morning in late September I helped lay to rest my friend and mentor, entombed in a simple casket made of chestnut by Trappist monks. Chestnut because, as Ian told me afterward, “He was bemused by the five walnut trees surrounding his house; they always dropped walnuts onto the roof in the fall, which boomed and thudded at random times on the roof and deck and could make staying outside a bit of an adventure.”

May our Lord bless you, Professor McLean, in whom Chronicles and I have lost a devoted friend.

Leave a Reply