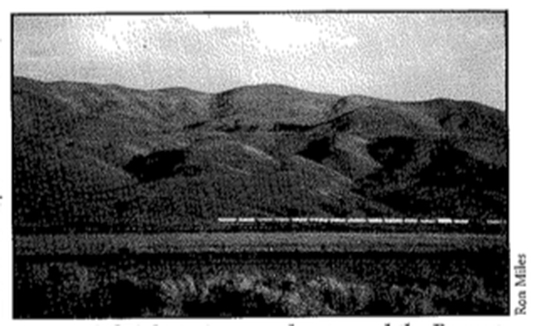

The only interruption in 32 hours of driving was a five-hour respite in a no-star motel somewhere in western Nebraska. Physically exhausted and emotionally inebriated by the nearness of the destination, I marveled at the sight of a Union Pacific freight train, eastbound, in the evening’s final thrust of amber sunlight. It steadily snaked its way through a lush, green valley in preparation for its ascent of the Pequop Summit. The events of the next few days would etch that image into my mind.

An hour later, the parking lot of the Stockmen’s Hotel and Casino in downtown Elko, Nevada, became the site of happy reunions and long-awaited introductions. The National Hobo Association’s Rendezvous 2000 had attracted an unusual assortment of souls, all afflicted with wanderlust. They came to celebrate the history and folklore of the American hobo.

While hoboes nowadays are about as common as bowling-alley pinsetters, there are still a handful of remaining practitioners. Several arrived in Elko from all parts of the country as ticketless passengers on a national rail system that comprises an ever-decreasing number of companies. Omar, a youngish “knight of the road” who leads a life devoted to social activism, had set out from a Burlington Northern yard near the Mississippi River in Wisconsin. He was almost embarrassed to admit that he had to complete die last leg of his trip by bus. Busted by high-tech railroad “bulls” armed with strategically placed video cameras that spotted him crouched in the well of a “double stack” container ear, Omar was promptly detrained and escorted from die property of the Union Pacific Railroad. Undaunted by the experience, Omar shrugged, “Things could have been a lot tougher than that. I’ve been treated plenty worse.”

For many, the coming of the railroads in 19th-century America made the urge to ramble irresistible; economic downturns in the century that followed made it mandatory. The dominant representation of the hobo is still that of the down-and-out itinerant worker of the Depression era. More recently, grossly exaggerated horror stories of serial killers A and vicious gangs riding the rails of America have had a calamitous effect on the public’s perception of hoboes.

Those of us who gathered in this high desert country in late July were given a more accurate view. One workshop, dealing with recent firsthand accounts and hosted by Bruce “Utah” Phillips, the hobo-cum-folk musician, quickly became a mentoring session. Utah (traditional hobo etiquette dictates that such monikers are the sole means of identification used among the ‘bos) was joined by Luther “The Jet,” who holds a Ph.D. in French literature.

They politely fielded the questions of a curious audience in the small exhibition hall of the Elko County fairgrounds. But it was apparent that their interest lay in a dialogue with about a half-dozen young hoboes carrying the layers of dust that they had accumulated en route.

“Never dangle your legs from an open boxcar door on a moving train,” the experienced Phillips cautioned. He explained that braking even a slow-moving string of cars can cause the heavy door to slide shut quite quickly, with fatal results. He leaned forward from his perch on a folding chair. Hands, usually fisted and tucked inside the apron of his bib overalls, came out to animate his instructions. “Look around for an old spike and use a rock to lodge it tightly into the door track. And sleep with your feet facing the front of the train. In a quick stop, you might break your legs, which is no good. But it’s better than a crushed skull.”

After about an hour of “jawboning” on such matters, Phillips made a last call for questions in an effort to maintain some semblance of a schedule—something of a foreign concept—and a fellow who hadn’t been shaving for very long freight train meanders toward the Pequop Summit near Elko, Nevada. sheepishly raised a hand. “What are we supposed to do about women?” he asked, in a nervous but sincere voice. As the crowd snickered, I braced myself for what seemed like a perfect opportunity for one of the quick-witted elder ‘bos to crack wise. Instead, Phillips silenced the chucklers with a steely gaze. He turned to the young man and spoke, unashamedly, of the toll that wandering ways had exacted upon relationships in his own life. He was very candid in offering ideas more practical than many psychologists on dealing with the inherent perils of long-term separation between lovers.

The principal organizer of the event. Buzz Potter, edits and publishes the Hobo Times. The masthead of this official publication of the NHA boasts that it is “published periodically depending on available funds.” An editorial policy clearly states that the Hobo Times does not encourage freight-train riding, a statement most likely advised by the head of “Sunshine” tells of the days of hard travelin’ its legal-affairs department, listed as “No Bail” John. Potter’s personal résumé reads like a great American novel. He first reached for the grab irons of a freight car at the tender age of 15. With his fascination and curiosity aroused by the view of a Utah canyon from a boxcar, he went on to study geology and mineralogy at universities in Minnesota, New Mexico, and Wisconsin. He panned for gold in the Western states and explored for minerals from Alaska to South America. Eventually, he founded a successful mineral-excavation business, Bluewater Mining, from which he retired in 1995. Now, he writes poetry and produces films and CDs about hobo lore and history.

Rendezvous 2000 was more than just an opportunity for railroad buffs, hoboes, former hoboes, and hoboes-at-heart to share experiences and reminiscences. It was also a music and poetry festival. Minnesota’s Pop Wagner was the festival’s artistic director as well as a performer. Widely recognized as one of America’s premier folk artists, Wagner has performed similar duties for Elko’s more famous Cowboy Poetry Gathering. With his thick mustache, he embodies the spirit of two of America’s most cherished icons, the hobo and the cowboy.

While much of the credit for the stellar job of staging this event belongs to Wagner, the quality and quantity of talent on hand made the job easier. Featured performers included Utah Phillips, Rosalie Sorrels, Spider John Koerner, and Larry Penn.

Sometimes, and in some places, the wizardry that these veterans can conjure rubs off onto everyone else on the bill. That happened at Elko.

Marisa Anderson’s red-hot guitar picking lit the fuse of an incendiary act called “dolly ranchers” (no caps, and they don’t say why), four musicians from New Mexico whose music is as wild and free as the the hobo life.

Mark Ross is a 51-year-old kid from Butte, Montana, with slightly graying hair. If you scratch beneath the road dust on this guy, you can plainly see the vestiges of a ten-year-old, freckle-faced redhead with a cowlick who might easily have modeled for a Norman Rockwell painting. From beneath the sweat stained brim of his ranger hat to his well worn, shin-high, leather lace-up boots, Ross exudes an ingratiating, boyish charm in spite of the Camel Straight dangling from his lips.

Ross is committed to the persona he has created for himself The rose tattoo on his arm bears the Latin inscription “Mors ante servitium.” Its English translation: Death before work. He boasts of hitting the road at the tender age of 17. He was forced, he says, to leave his beloved cabin in the hills of New York City to look for work because of an illness in the family: “My parents were sick of me.”

Ross plays no fewer than a dozen folk instruments proficiently and has a vast repertoire of songs and stories. Hosting a workshop dedicated to the songs of Woody Guthrie, he dazzled listeners with a jazzy rendition of the crowd-pleasing “Do Re Me.” Before anyone had fully caught his breath, he launched into a moving rendition of “The Ballad of Tom Joad,” complete with an historical account of how Guthrie came to turn a Steinbeck novel into a song. At one time or another, Ross was called upon to accompany nearly everyone on the bill. In each case, he performed flawlessly.

The surprising cast of characters at this gathering of hoboes included social activists, musicians, poets, Ph.D.’s, geologists, folklorists, anthropologists, and even a professor of economics. Each played an integral part in getting the rabbit into the hat for the magic that would make this festival more than worthy of the 32-hour drive. When I close my eyes, I still see that freight train. And I see it in a whole new light.

Leave a Reply