“We don’t divorce our men; we bury them,” instructs Stella Bernard, played by a loony Ruth Gordon, in Lord Love a Duck (1966). That’s certainly better social policy than America has pursued since 1970, with no-fault divorce shattering families. No custody battles. No brawls over alimony and child support. No kids shuttled back and forth between mom and dad. No family-court trauma. No false accusations of spousal and child abuse. Just a funeral.

The line is one of the many delights of a surprisingly prophetic film that bombed when it came out, but now enjoys a cult following. It seems unlikely James Burnham saw it two years after his Suicide of the West was published. And it’s doubtful the filmmakers and actors read Burnham. But the movie might be retitled Suicide of California, Followed by America.

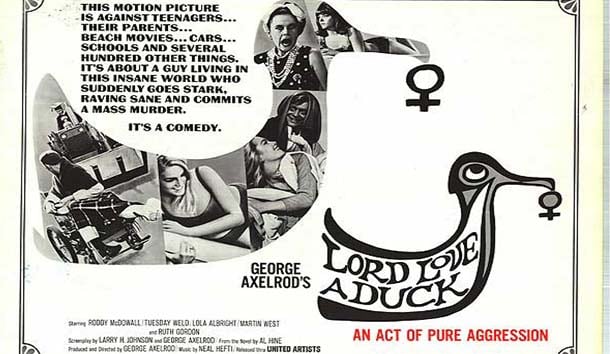

Seen today, Duck is practically a documentary of the social breakdown of the West, played out in the Southern California sunshine to a rock ’n’ roll beat. Based on a 1961 novel of the same name by Al Hine, it was the first of only two movies directed by George Axelrod, who also cowrote the screenplay. He’s best known for writing The Seven Year Itch, The Manchurian Candidate, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, and Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?

Duck usually is described as a black comedy. But it’s more, blending several genres into one of the murderous poisons that are part of the plot: beach romp, psychoanalysis sendup, marital farce, teen angst, and religious satire. It also was a key entry in the genre I call “Mid-60’s Leering”—films made as the old Production Code was being challenged, before it was abandoned in 1968. Another was The Loved One in 1965, adapted loosely from Evelyn Waugh’s farce of the California funeral industry’s glamorization of death, and stylistically similar to Duck.

Given what is shown today in theaters, let alone on cable TV or the web, these movies may seem tame. But at the time, they were revolutionary, displaying the breakdown of the society that made and showed them. They are cinematic specimens of the final cultural ascendancy of liberalism and its attempt to perfect man through the Great Society, abandoning censorship and atomizing the family. This time was the breaking point.

As Burnham observed in his book,

[W]e may assert that liberalism believes man’s nature to be not fixed but changing, with an unlimited or at any rate indefinitely large potential for positive (good, favorable, progressive) development. This may be contrasted with the traditional belief, expressed in the theological doctrines of Original Sin and the real existence of the Devil, that human nature had a permanent, unchanging essence, and that man is partly corrupt as well as limited in his potential.

American society was trying to declare itself Great, and Duck responded, “Sounds like suicide.”

Lord Love a Duck’s title derives from a nonsense expletive that hasn’t caught on in America. But P.G. Wodehouse squeezed a description into The Coming of Bill in 1920: “‘Well, Lord love a duck!’ replied the butler, who in his moments of relaxation was addicted to homely expletives of the lower London type.”

The phrase is used only in the title song, sung by the Wild Ones. It’s an upbeat typical mid-60’s rocker like something from the Dave Clark Five stuck on depressing lyrics:

Hey, Lord love a duck

Don’t nobody care

So tired of swimmin’

And getting’ nowhere

Down on my luck-o

Stuck in the muck-o

Lord love a duck

(Duck quack)

The movie features two former child stars who are too old physically to play their parts as high-school seniors: Roddy McDowall at 37, and Tuesday Weld at 22. But their maturity expands into roles too weighty for teen stars. Roddy plays Alan Musgrave, self-nicknamed Mollymauk, after a Southern Hemisphere albatross. He’s a genius, a hypnotist, a black belt in karate who beats up the captain of the football team, and holds a copy of every physical key for their high school. Today, we would recognize him as a nerd headed for Silicon Valley to start an internet firm and become a billionaire nuisance.

Mollymauk becomes Svengali to Barbara Ann Greene, the perfect name for a nice Southern California blonde who longs to become a Hollywood star—and, as her mother says, is named after two of them: Barbara Stanwyck and Ann Sheridan. Although there’s no intended connection, when you hear her name you want to sing the Beach Boys’ version of “Barbara Ann,” which came out a couple of months after Duck. Tuesday was in the full bloom of her beauty and plays the part to cynical perfection.

The movie disorients from the beginning. The title tune is played over a fast montage of scenes from the movie, giving away much of the plot, mixed with scenes of Axelrod and his movie crew filming. The narrative starts at the chronological end, with Mollymauk locking himself into his high school. The police break in and arrest him.

A lady psychologist, smoking a cigarette, gives him Rorschach tests. He sees birds, flowers, trees, and a river.

“You’re fighting me,” she says. “Don’t fight me, Alan. I want to help you. These things are supposed to be dirty.” Then she screams, “You’re hostile, you little creep!” He spits psychological gobbledygook back at her. Then she agrees to give him a tape recorder for his confessions.

Speaking into the mic, he says Barbara Ann is an expression of “the total vulgarity of our time.” Then begins the flashback to the beginning of the story.

After manipulating a meeting with Barbara Ann, Mollymauk uses one of his keys to break into a building we see is named Consolidated. It’s that particularly deep circle of the Inferno known as the American high school.

“I went to Longfellow last year,” she says, calling it “dinky and old.”

“I went to Irving,” he replies.

The old schools, named after American literary figures, were ripped down and replaced with progressive and aseptic Consolidated. The principal is played by Harvey Korman, nervously chewing the erasers off yellow No. 2 pencils. This was the era of the federal Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, which dumped billions into local schools, effectively consolidating them into a national system that is still turning out ever-larger percentages of dunces. At the same time, University of California President Clark Kerr was imposing his “multiversity” consolidation on the state, one model for the Behemoth U against which Russell Kirk used to inveigh.

Barbara Ann says her major is “adolescent ethics and commercial relationships” and she is taking “plant skills for life. They used to call it botany or something. They’re making me take it, too.”

“How medieval of them,” Mollymauk sympathizes. If only it were.

By 1970 that relativist plague spread to my Wayne Memorial High School in Wayne, Michigan. That year, among other reforms, the principal purged the old English classes and instituted a new curriculum with such classes as “Wheels” and “Fashion,” where students read Hot Rod and Cosmopolitan instead of Shakespeare, Longfellow, and Irving.

Consolidated High is the height of liberal education, which Burnham describes:

For liberalism, the direct purpose of education cannot be to produce a “good citizen,” to lead toward holiness or salvation, or to inculcate a nation’s, a creed’s, or a race’s traditions. . . . Properly educated, and functioning within a framework of democratic institutions, human beings will understand their true interests—which are peace, freedom, justice, cooperation and material well-being—and will be able to achieve them.

Later in the movie, Stella describes Bob Bernard: “My son’s a product of the California school system. Couldn’t write a simple English sentence if his life depended on it.”

In explaining California’s problems in a 2009 speech, Rep. Tom McClintock, our best conservative congressman, used words Californians commonly hear from state Republicans:

You have to remember the Golden State in its Golden Age. A generation ago, California spent about half what it does today after adjusting for both inflation and population growth. And yet, we had the finest highway system in the world and the finest public school system in the country.

That doesn’t say much for the rest of the country.

Religion was expunged from the public schools by the U.S. Supreme Court in the early 1960’s, so the kids of Consolidated High are left to make up their own ethics, based on astrology and gypsy fortune tellers. Barbara Ann says she wants to be as popular at Consolidated as she was at Longfellow. “Everybody has got to love me—everybody,” she pleads to Mollymauk, who is eager to fulfill her desires. “My horoscope says I’m going to be famous. I’ve been very good. I haven’t done bad things with boys. Well, a little. But not really bad. And only if I liked a boy.”

Barbara Ann calls her parents by their first names, Marie and Howard—one fad that fortunately seems not to have caught on much, even in California. Marie, a cocktail waitress played by Lola Albright at age 41, says, “Everybody thinks we’re twins,” reflecting California youth mania, a studied immaturity that has spread throughout the country, indeed the world.

Marie is divorced, like seemingly everybody I know in California today. One friend who has stayed married for three decades told me his daughter came home from public high school one day and said, “Everybody in school says we have an Ozzie and Harriet family.”

When Marie arrives home with a boyfriend whose name she can’t remember, Barbara Ann asks if he’s married. Marie gives a twisted reply, “Honey, you know I never go out with a married man on the first date.”

This, too, is part of the liberal’s blueprint. Burnham writes that liberalism is

secular at least in tendency and emphasis even when individuals are or regard themselves as Christians. Many liberals . . . have openly broken with Christianity. . . . Moreover, for most persons today, non-liberal as well as liberal, religious belief has become departmentalized, restricted in its influence on life and conduct.

Christianity cruises into Duck at the First Drive-in Church of Southern California / Worship in the Privacy of Your Own Automobile / Pastor Philip Neuhauser, as the sign in front reads. From his office, Phil, as everybody calls the pastor, speaks into a microphone to the churchgoers sitting in their cars:

If Leviticus were written today, we might very well call it “Mr. Levy’s book.” . . . Yes, the Lord sure as shootin’ does answer our prayers. . . . Because, whatever happens, that’s the answer. . . . Harping all the time does not make you an angel.

This is a sendup of the Rev. Robert Schuller and the “positivity thinking” preached at the time at his drive-in Garden Grove Community Church a couple of miles south of Disneyland. Schuller is still around at age 87, although he recently lost his Crystal Cathedral. After his church went bankrupt, the Catholic Diocese of Orange bought it in 2012 and renamed it Christ Cathedral. It remains the ugly glass edifice designed by Philip Johnson.

At the church offices we meet Stella’s son and apparent only child, Bob, a college student majoring in marriage counseling. He helps Phil conduct a class on “petting” for ten high-school girls, including Barbara Ann. The theme: “Is it love or is it sex? Six surefire ways to tell the difference.”

Bob chaperones the girls at a beach party on Balboa Island, the exclusive Newport Beach property where John Wayne lived his last decades. The kids wiggle up and down to the Watusi and other 60’s dance steps, the girls in thin bikinis. Naturally, Bob romances Barbara Ann. Behind a rock, Mollymauk, his own personal NSA, tapes the banter and confronts her with the playback. “I want him,” she says.

Here’s where we meet Stella, who explains, “My son is a dear boy. He’s also a total idiot.” She blows a kiss at Bob. “Takes after his late father.” She explains her husband’s recent death: “All psychosomatic. Absolutely nothing wrong with him physically.”

After Stella finds out Barbara Ann’s mother, Marie, is a cocktail waitress, she rejects Bob’s interest in the girl. In shame, Marie commits suicide by overdosing on sleeping pills, a symbolic wipeout of the whole sun-speckled California scene. As Burnham writes in the Afterword to the 1975 edition of his book, “If modern liberalism is the ideology of Western decline and suicide, no ideology or doctrine of Western revival is visible.”

Marie’s suicide opens the way for a marriage, just as Bob is starting his marriage-counseling practice. The marriage breaks down a month later when he refuses to let Barbara Ann go for a screen test for a movie that becomes Bikini Widow. “You promised to love, honor, and obey me,” he shouts.

She shrieks back, “I might have been a little hysterical at the ceremony. But I never said anything as dumb as that.”

Barbara Ann tells Mollymauk that she wants a divorce. He repeats Stella’s stricture about burying husbands.

Mollymauk then tries to kill Bob in four ways: tripping, two kinds of poisoning, and cutting the brake line on Bob’s car. On the way to Consolidated’s graduation ceremony, where Mollymauk is valedictorian, he is pushing Bob, now disabled, in a wheelchair past a bulldozer. Mollymauk jumps on and chases Bob, using the bulldozer’s blade to throw Bob into the air, then crashes the dozer into the platform holding the principal and other dignitaries. It’s not clear from the movie that anyone dies, except possibly Bob. But the movie trailer says Mollymauk is a mass murderer.

The movie flips back to the present with Mollymauk speaking into the tape recorder:

Of course, O nation of brainwashed television viewers, who worship graven images in the shape of family-sized tins of spray-on deodorant, you have guessed it. I did it for love. L-O-V-E. Love. I did it for you, Barbara Ann. I got you everything you wanted. And if this doesn’t make you famous, nothing will.

There’s a brief flash of Barbara Ann, wrapped in white mink, smiling at the opening of Bikini Widow, as the paparazzi flashbulbs pop. Mollymauk’s last words into the mike: “You poor bunny.”

You poor bunny, California. You poor bunny, America.

Leave a Reply