Some good folks in my hometown are planning a reunion of my high-school class, which, come June, will have graduated 50 years ago. It was a class of about 500. Three hundred are known, of which 53 are already deceased. (Our average age is 67.) It is a strange and unsettling experience to contemplate the death of people whom I last saw in the flourish of youth, some of whom I had known since the first grade, and some of whom I thought were great in vitality and would probably outlive me. About 200 are as yet untracked, and some of those will doubtless be missing also when the roll is called.

It was the last all-white class in my city. The junior class had already begun token desegregation with one black girl. Most folks looked on that with distaste or apprehension. The more enlightened, who had been to Chapel Hill, felt that it was the correct thing, providing justice to the more deserving of a group that had suffered denial of opportunity and serving to make us look good in the opinion of the United Nations, which good opinion, for some reason, we were supposed to covet. At any rate it was inevitable and, we were assured, would be gradual and limited in scope.

Our class was about 85-percent Carolina Anglo-Celtic (if you count as Anglo-Celtic a number of ancestors who had the good sense to leave Germany in the late 17th and early 18th centuries). About ten percent were carpetbaggers, who were being happily and painlessly civilized, and about five percent Other, perfectly accepted. The high school encompassed the entire white population within the city limits. There were the children of millhands and the children of mill owners. I do not recall any class conflict (although it is true that the snootier of the rich youth had departed for private academies in Virginia or military schools). Standing was based on sex appeal, athletic prowess, sociability, and, a distant fourth, academic achievement. As editor of the school newspaper, unathletic and unclubbable, my status was somewhat indeterminate. I did have on my staff a future lady author of salacious novels and the daughters of a famous poet and a well-known historian. In those quaint days our sports teams were known as the Purple Whirlwinds, or Whirlies for short.

Everybody had kinfolk in World War II and not a few had them in the large section of a cemetery devoted to casualties returned from Europe (like my uncle) or the Pacific. Most, if they had cared to, could claim eligibility in the Sons or Daughters of the Confederacy, and a majority probably in the Sons and Daughters of the American Revolution. We had all been raised in the horrific shadow of the atomic Cold War and Korea, where a local fellow had been an ace. We had a certain feigned fecklessness as a result. Vietnam had not yet been heard of. Never in life since have I found the girls sweeter or lovelier.

We were Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians, Lutherans, and Episcopalians, in that order of magnitude. There were a few Jews and Catholics. Many of the first two thought it a sin to go to the movies or a ball game on Sundays, and that one drink was a certain road to Hell (which is sometimes true). There was no parochial high school in town, but there was a large hospital run by the exotic Sisters of Charity. I sold newspapers there every morning and afternoon, and my violently Protestant great-aunt was housemother to the nursing students, almost all of them non-Romanist locals. She would omit the word catholic in the Creed the same way some good folks like to omit “one nation indivisible” from the Pledge of Allegiance.

There is no need to wax nostalgic. Wherever there is Man there is sin, suffering, and sorrow, and, as someone has said, youth is greatly overrated. Farmers and workmen, of both races, could still be seen in those days in bib overalls and shirtless, and a few people still came to town in a wagon led by a mule. Most of us children and some adults went barefoot in the summer except to church. A great many older people had a very limited education. Spittoons were common. No question that folks, white and black, enjoy a higher standard of living today—though they also seem a good deal more harried and discontented and somehow alienated in a way not known in poorer times. Spontaneous music making, humor, innate dignity, good manners, and kindness are much rarer now.

Government was in the hands of local gentry, who were generally honest and easy on taxes, which they knew the working majority could ill afford. The two newspapers and one television station were locally owned and reflected, to a considerable extent, local culture and opinion. The lords of industry, if not all local, were all in-state and known. Neighborhoods were segregated, but not as rigidly as in the North. There was much peaceful overlap, especially in the older parts of town and in the rural fringes.

A child lost in any part of town was sure to find help and kindness. At nine or ten years of age I would ride the bus downtown on Saturday and stay all day watching movie serials, dining on hot dogs and Dr. Pepper, and perusing the comic books at the newsstand. It occurred to no one that a child alone might be in any danger, though it was a real city. We had a skyscraper of 17 stories, the tallest in the state, unmatched even by Charlotte. Still, you could not go anywhere in public without encountering someone you knew.

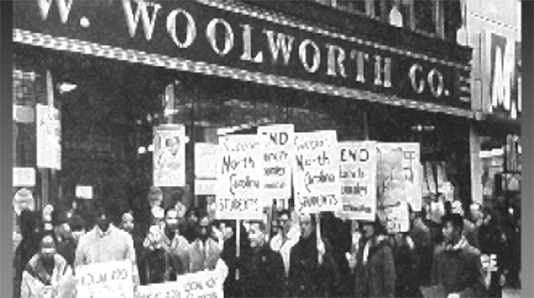

The violent “nonviolent civil-rights protests,” for which our city would become famous in a few years, had not yet erupted. Ask any police or fire veteran about the “nonviolence.” My father trained and captained the first black fire company. His company was not immune to ambush by snipers who were “protesting” by arson. I had enjoyed my white privilege many times at the Woolworth’s lunch counter, which Jesse Jackson was about to make world famous for something besides its BLT sandwiches. I have never seen this mentioned anywhere, but just across the street was the site where young Will Porter, later famous as O. Henry, posted his caricatures of the local carpetbagger (of the original sort) in his uncle’s drugstore. The carpetbagger, Albion Tourgée, soon went back to New York and published a book called A Fool’s Errand. A few blocks down, just south of the railroad tracks, was the place where Otto Wood shot the Jewish pawnbroker. As memorialized in the Doc Watson song, Otto later escaped from the state pen and went somewhere out West, where he finally met a lawman with a trigger quicker than his.

My grandfather would undoubtedly be damned today as a “racist,” but I saw him more than once feed fatherless black families for free out of the meager proceeds of his semirural grocery store. And as a child in the era of Jim Crow, I enjoyed afternoon naps in the house of his highly respectable black neighbors. It was two stories but had a tin roof, delightful when it rained. I was country when country wasn’t cool.

Nobody not blood kin would have told an 18-year-old man, who could be summoned at any time to die for his country, that he could not drink and smoke. Girls had to be more circumspect in public. Marijuana was something we knew about through drive-in movies, and we had never heard of Timothy Leary. Nowadays, those who like that sort of thing and know where to look can find a street corner where they can purchase any kind of mind-altering chemical they want.

We now imitate our superior Northern fellow citizens, declaim the glories of integrated society, and flee to the suburbs or even adjoining counties. Nobody really believes any more in those glories, except in official and media rhetoric. The media portray a city of happy brotherhood that bears no relation to reality. Black people reign in the schools, but their tenure has been brief. It is already giving way to the sovereignty of Mexico, as are whole sections of the city. Hmong, Iranians, Jamaicans, Africans, Chinese, Hindus, and assorted Others are very visible but will doubtless never be able to challenge the Mexicans.

Carpetbaggers are much more numerous today, Rust Belt fugitives, but most live in enclaves with houses worth three or four times what most locals, white or black, can afford. In fact, everybody is from somewhere else, and everything—newspaper, television, business—is controlled from somewhere else. The streets have a feel of tension and barely suppressed racial hostility like a big Northern city. All are strangers, and the only local culture and opinion and tradition that survive are found in the small towns and country where the natives have fled. Not long ago one could not step too far out of town in any direction without finding tobacco fields, corn, cotton. Now the subdivisions stretch on forever, calibrated by income level.

Today local government is largely the plaything of self-anointed black leaders and their accomplices, white public-sector entrepreneurs. Both are invariably corrupt and eager to exploit the votes of those who pay no property taxes for their private profit and entertainment at the expense of the middle and working classes who do pay property taxes. Violent crime is a lot more common than in older days. Black judges and juries, unlike the white judges and juries of earlier times, tend to be lenient about black-on-white crime. But exactly like the white judges and juries of earlier times, they continue to be lenient about black-on-black crime. Of course, any boys who today engaged in the BB gun fights that we used to have would now be prosecuted to the fullest extent of therapy.

And what does it all mean? It seems to me that the current and the rising generations are rich in materiel but increasingly impoverished in their humanity—too impoverished even to know what is missing. That seems to describe what it now means to be an American, once fortune’s child in the land of the free and the home of the brave.

Our forebears planted trees and built houses that their unseen descendants would enjoy, and worked and fought to bestow the blessings of liberty on their posterity. Americans long ago abandoned that sort of backwardness to become people of the Now. It is “un-American” even to think about posterity or to consider the future except as a utopia of universal prosperity, equality, and technological wonder. Those of us who are not good “Americans” have to fear for posterity. But Christians have a duty to hope for the best, and no one knows what turns history will take. When I see my sturdy grandson taking his first bold steps, I know it has been and is yet worthwhile to hope.

Leave a Reply