You know within a few moments of meeting him whether a “celebrity” is going to be a regular guy. It’s not just the winning smile, or his willingness to pose for endless selfies; it is whether or not he’s matured around a recognizable value system, the presence or otherwise of a due sense of modesty about his achievements, the way he holds himself away from the public spotlight.

Thirty years ago, in London, it fell upon me to arrange for a suitably illustrious guest to speak at a dinner for housebuilding-industry executives and their wives. I remember approaching one or two now-defunct stars of British stage and screen, as well as Carol Thatcher (the prime minister’s daughter), and various others whom I recall with something closer to nostalgia than real fondness. Most were already engaged on the night in question, and the few who weren’t balked at the modest fee I was able to offer them. At the last moment, a colleague suggested that I try the anchor (or reader, as they were then called) of the nightly BBC Television news bulletin, Richard Whitmore.

Whitmore himself answered the number I dialed, and listened briefly to my pitch. He not only said that he would come to the dinner, but told me he would be delighted.

When the night arrived, Whitmore appeared for our rendezvous a minute or two late and apologized profusely for his lapse. He had taken public transport in from his suburban home, and the train had broken down in a tunnel en route. Trim and neatly dressed, bespectacled, of around middle age, he seemed like a thoroughly unexceptional and pleasant Englishman of a sort perhaps less notable then than it is now. When first alighting at the station, he had extended his hand and—as though his name might not be immediately familiar—warmly introduced himself. We walked together to the hotel where the dinner was held, and along the way I observed examples large and small of Whitmore’s unfeigned charm and modesty. Considering this was a man seen by some eight million viewers each weeknight, he seemed touchingly surprised when an occasional passerby stopped to greet him. When I asked him if he minded the attention, he smiled and shook his head. “Honestly, though, you sometimes wonder what all the fuss is about . . . For some reason or other, just because you can read off an autocue, people assume you’re a great sage.”

When we got to the door of the hotel dining room, Whitmore asked me a shade anxiously if he should perhaps pay someone for his meal, and I assured him that, no, it was all included. He accepted the check I later gave him—for around $400—in the same gracious spirit. When the time had come for his speech, Whitmore told us about some of his earlier travels for the BBC, including a stint in Belfast during the worst of the sectarian violence there—which, he claimed, “wasn’t the least bit dangerous, really.”

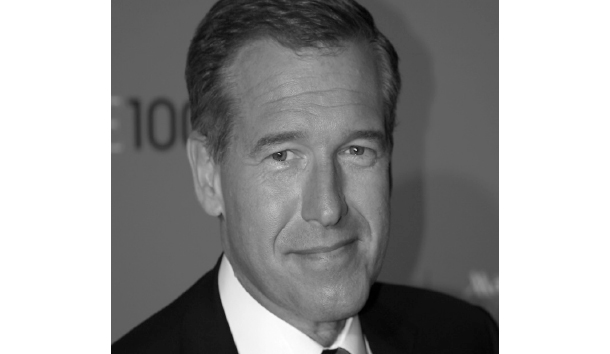

I raise all this only in relation to Brian Williams, and the apparently widespread delusion that he should be seen as a figure of some substance. If so, it can only be in the sense that he illustrates a painfully observable fact about modern life: Almost anyone who appears on television, however trite his role, automatically attracts the moronic hero-worship that governs nearly everything in 21st-century Western culture. It is not true that we are becoming a less deferential society; rather, our respect has been transferred from the old elite to, among others, those sufficiently adroit to sit on a chair and read out a script to us.

At the heart of the Williams affair lies, I think, not so much the question of his alleged brush with enemy fire in Iraq, but whether we should properly treat such people as working journalists or entertainers. To the Richard Whitmore school, “anchors” were by and large like old-fashioned messenger boys: Here was a list of the day’s news, there was the public, and your job was to ensure that the one was delivered to the other in as efficient and courteous a way as possible. Such individuals would never have considered imposing their own personalities on the transaction. It’s not that Whitmore lacked either self-confidence or professional experience, as I discovered during the course of our evening together. But while on air, he invariably concentrated his intellectual firepower on distilling various points of view, rather than dramatizing them. Remembering the quietly efficient way in which he did his job, I wonder what the relentless push for “personalities” like Williams to read our news really amounts to.

Leave a Reply