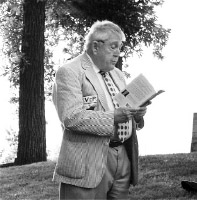

Thomas H. Landess died from a sudden illness on January 9, 2012. He was 80 years old. His death was a shock to his family and his many friends. I last heard from Tom two days before his death, an event that was out of mind, so warm and hopeful were his comments. I had sent him a copy of my unsubmitted review of the movie The Help just to see what he thought of it. Tom was most complimentary. In his usual modest and self-effacing fashion, he concluded, “I am going to write about this myself—by comparison with yours, a cowardly piece.” That was Tom, always the encouraging gentleman.

During the early 1960’s, my good friend the late Haywood Hillyer and I were publishing a little conservative magazine in New Orleans called The Liberator. By letter dated June 4, 1963, I heard from one “Prof. M.E. Bradford, Chairman, Dept. of English, Hardin-Simmons Univ.” In it he said that Frank Owsley, Jr., had suggested he send his “brief paper on liberal rhetoric” to us for consideration. Bradford was 29 years old at the time. We hoped to publish it, but unfortunately The Liberator went out of business before we could. Nonetheless, that was the beginning of my friendship with Mel Bradford and, shortly thereafter, with his best friend, Tom Landess. Neither Mel nor anyone else could have had a better friend than Tom. It was through Mel that I met Tom, although I can’t remember when or where I first met either of them. I do know that by the time the Southern Literary Festival was held at the University of Dallas in 1968, we had become friends, and they invited me to the conference. Much to our delight, Robert Penn Warren, Allen Tate, John Crowe Ransom, and Andrew Lytle were the speakers.

So by the time Tom died, we had been good friends for over 40 years. How specially favored I was to have known, respected, and admired Tom Landess for so long! He was very special in so many ways: a true Christian gentleman (Southern, that is—top of the line); a fine scholar, teacher, and author; a devoted family man and friend; an interesting, humorous, and engaging companion; and a conservative in every worthy sense of the term. He was fiercely loyal to his principles and greatly bemoaned the fact that we seemed to be bogged down in what Bradley J. Birzer called “a wasteland of the inhumane and the corrupt.” To use Tom’s own words, he was opposed to “a society driven by the engines of pride and greed” and to “the rise of modern materialism and the advent of the secular society.”

Much can be learned of Tom’s own beliefs from his 1979 essay in Modern Age entitled “James Joyce and Aesthetic Gnosticism.” Tom did not swim in “the pool of self”; he chose not to reject “the traditional pieties.” Like Saint Paul, Tom “gave himself completely to the all-absorbing other than self.” Unlike Stephen Dedalus, Tom was fully committed to social custom, family, tradition, church, the created order, and God. His faith did not stand in “the wisdom of men, but in the power of God” (1 Corinthians 2:5).

Following the Southern Literary Festival, Tom drove Mr. Ransom to the airport. While they were waiting for the flight to be called, they entered into a conversation about death, and, according to Tom, Mr. Ransom said, “I think we’re meant to die so others can take our place. When my time comes, I’ll be happy to make room for somebody else.” I’d like to think someone would be able to take Tom’s place, but I fear that’s only wishful thinking.

Leave a Reply