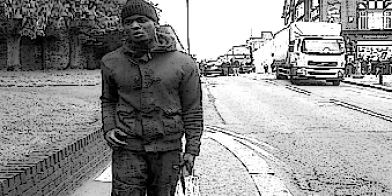

The last major outburst of Muslim terrorism in London was on July 7, 2005, when four suicide bombers killed 52 people on London’s buses and subway trains. Of late, Londoners had begun to think that they were safe and that these acts of Islamic terror now only happened in such faraway places as Mumbai, Toulouse, and, of course, at the Boston Marathon. But suddenly on May 21 there was a new appalling outburst of fanatical Islamic violence in Woolwich, London. Michael Adebolajo and Michael Adebowale, two British Muslims of Nigerian ancestry, deliberately ran down British soldier Lee Rigby with their car, crushing him against a road sign. They then stabbed and hacked him to death with knives and cleavers, nearly beheading him, shouting “Allahu akbar!” For 20 minutes the killers were photographed striding up and down the street, displaying hands dripping with blood and shouting that the murder was revenge for the deaths of Muslims abroad. Armed police arrived but were attacked with knives and a gun. A specially trained female police officer shot them both with great accuracy, and they were taken away in an air ambulance. The terrorists had achieved their purpose of horrifying the entire population with a singularly bloody and very public murder in the name of their violent religion.

Cutting short his visit to Paris, the prime minister flew home to call emergency meetings of his colleagues and the leaders of British security forces.

The killers had been planning this attack for some time, and police have already arrested several accomplices.

Over the past decade security services and police have been regularly tracking down and arresting Muslims conspiring to commit acts of terror. In 2008 Parviz Khan, a man known for his violent and extreme Islamic views, was jailed for life for plotting to kidnap a British soldier and film his beheading. It is a tribute to the vigilance of the security services that so many conspirators have been detected, but such a proliferation of attempts is also an indication of how very many violent Muslim radicals are hiding in Britain’s otherwise peaceful society.

A few days after the Woolwich murder, a bearded Muslim inspired by the widely reported London attack stabbed a French soldier, Cedric Cordier, in the neck in Paris. A few minutes before, the killer can be seen on security footage praying close to the place of the attack. Prayer before murder!

The pattern is clear. The United States, Britain, and France, who have sent soldiers to fight against Islamic aggression in Africa and Asia, from Afghanistan to Mali, are now faced by the enemy within, for their own Muslim citizens have brought terror to their cities. Only months before the Paris incident another Muslim terrorist in France had killed three French paratroopers as well as a rabbi and a number of Jewish schoolchildren. Such men are increasingly difficult to detect, for they are not part of a coherent Al Qaeda-style terrorist organization that can be penetrated and broken up. They belong to smaller scattered groups, made up of the attendees of radical mosques where hatred is preached and devotees of internet sites that not only incite Muslims to violence but explain how to go about it.

The situation has created a crisis for the British government. Mrs. Theresa May, the minister on whose desk the problem rests, is considering giving the security services extensive and automatic powers of surveillance over phone calls and e-mail communication, but her proposal has been condemned as a “snooper’s charter,” incompatible with the traditions of a free society. Likewise, there is fear that she will make much more extensive use of her power to block or remove whatever the government considers “extremist messages” from the internet; since 2010, at least 5,500 such items have been taken down. If she lowers the threshold of what constitutes incitement, the law will be used to harass many groups besides radical Islamic preachers and agitators—people who are not dangerous but merely politically incorrect. It is difficult for democracies to defend themselves against violent subversion without compromising their own commitment to freedom of speech, freedom of religion, and individual privacy. The greater the threat, the more acute the dilemma.

The situation is not helped by the willful blindness of Britain’s many loyal and quiescent Muslims, who, whenever violence breaks out, bleat that Islam is a religion of peace. It is not. The Koran preaches violence and coercion, and the history of Islam shows how dutifully the followers of its prophet have carried out his edicts. The majority of individual Muslims in Britain genuinely want a quiet life of work, family, and the pursuit of happiness, but they are quite unable to see that these men of violence are good Muslims. Yet at some level they must recognize this reality, for they have not exactly been vigorous in betraying these terrorists and thugs to the authorities.

Leave a Reply