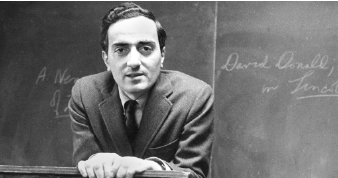

Eugene Dominick Genovese, r.i.p. Gene Genovese, 82, one the more important and controversial American historians of the 20th century, passed away quietly at his Atlanta home on September 26. A dockworker’s intellectually precocious son, who came up through Brooklyn College and Columbia University, Genovese embraced Marxism early in life, almost inevitably. And there was a similar inevitability, perhaps, in his return in later years to the Church of his fathers. Though Gene never lost his belief that class hegemony was the active agent in history, his stance as historian was never the shallow literal-mindedness of most of Marx’s American followers. Early on, he wrote of the leaders of the antebellum American South, who were his main subject, “If we blind ourselves to everything noble, virtuous, honorable, decent, and selfless in a ruling class, how do we account for its hegemony?” Genovese gained national notoriety in 1965 when Richard Nixon demanded the firing of the young Rutgers University professor for his public embrace of the enemy in the Vietnamese conflict. (Gene told me that later on Nixon assured him in private that there was nothing personal in his attacks; it was just politics.)

Gene, I think, thrived on controversy. A small man, he had an urban tough-guy (with a heart of gold) demeanor that women liked. He was scathingly critical of the shallow, self-indulgent, and immoral behavior of the New Left. That, and his sympathetic embrace of the South, finally made him bête noire to the American left, something symbolized by his receipt of the Ingersoll Foundation’s Richard M. Weaver Award. American academics are nothing if not cautious and conformist—the more radical, the more so. They could not understand Genovese, whose seemingly contradictory stands were based on intellectual and moral conviction rather than career calculations. His learning in history, philosophy, and theology exceeded that of any 20 run-of-the-mill scholars, and he always respected genuine intellect and integrity. His support for M.E. Bradford, the dean of Southern conservative scholars, was forceful and unflagging. Genovese’s rightward inclination was shared and perhaps led by his wife and collaborator, Elizabeth Fox-Genovese, whose misgivings about abortion led her away from conventional feminism and into the Catholic Church.

We historians know that our work lacks the imperishability of great art. This is not the place to discuss Genevose’s works or his view of the Old South, which, as he well knew, I disagreed with on major points. Gene and Miss Betsey had no children of their own, but they gave very substantial personal and professional friendship to a literal host of people. That may be their greatest legacy. They kept up such generosity despite several cases of spectacular betrayal by its recipients. Though still productive, Gene had been in feeble health since the passing of Miss Betsey in 2007. Knowing his time was short, he made an exemplary Christian end of quiet acceptance and hope for the next life. For the rest of my days, I will contemplate invaluable friendship and the import of an inscription he wrote in a copy of one of his last books that he sent me: “The South will rise again!”

Leave a Reply