Noted British conductor Sir Simon Rattle has described Europe at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries as “sitting on a volcano,” with the rise of radical ideologies, revolutionary ferment, amazing advances in science, the questioning of all previous certitudes in faith, and new currents in the arts.

This was especially true in opera as well as in symphonic music, where two giants— Anton Bruckner (1824–1896) and Gustav Mahler (1860–1911)—towered over others. The two men are often grouped together, as they wrote lengthy symphonic works and composed numerous choral and vocal selections. Both men were musical geniuses who employed all the many achievements, techniques, and accumulated wealth of musical knowledge in their respective compositions. Mahler looked resolutely forward musically to the uncertainties, to the angst, to the disjointedness, and to the 20th-century collapse of Western culture’s civility and orthodoxy, while Bruckner, incorporating the same rich artistic tradition and heritage, resolutely looked backward to what had gone before. He offered in sound an incredibly and uniquely creative defense of that tradition and its orthodoxies.

Bruckner was born in Ansfelden, in Upper Austria, on Sept. 4, 1824. His father, who died when Bruckner was only 13, was the local schoolmaster. For much of Bruckner’s early education, he attended school at the famous nearby Augustinian monastery of St. Florian, where he developed an extraordinary interest in and familiarity with the great Baroque musical heritage created and cultivated by the Catholic Church. There he received extensive training in the organ, choral music, and violin—and he excelled brilliantly in all three. Because of his precocious talent, at an early age he became organist for the Augustinians. Bruckner’s firm Catholic faith, simple but profound, would be the incredibly rich and vibrant foundation for his later work as a composer—his, as he described it, “giving back to God in music what he had received from Him through grace.” He consciously took as his mentors Beethoven and, before him, the masters of the Austrian Baroque, who would form the essential inspiration for Bruckner’s later monumental symphonies.

Recognized for his unique talent, Bruckner later went to Vienna, where he eventually became professor of music theory at the internationally famed Vienna Conservatory and, later, at the University of Vienna. And it was there, in Vienna, that he made tremendous contributions over a 30-year period not just to the classical musical tradition of Europe but to the corpus of Western and Christian culture.

If that were the summation of his place in musical history and European culture, it would be quite significant. But Bruckner occupies in our modern age another role; he represents a veritable “sign of contradiction” against the cultural, historical, and religious decay that has engulfed Western and Christian society since his death in 1896. And he does this poignantly through his music—his fine choral music, his masses and motets, and, above all, his symphonies, which are, as some writers have rightly suggested, “great orchestral moments of prayer,” immense architectural constructs that point musically heavenward.

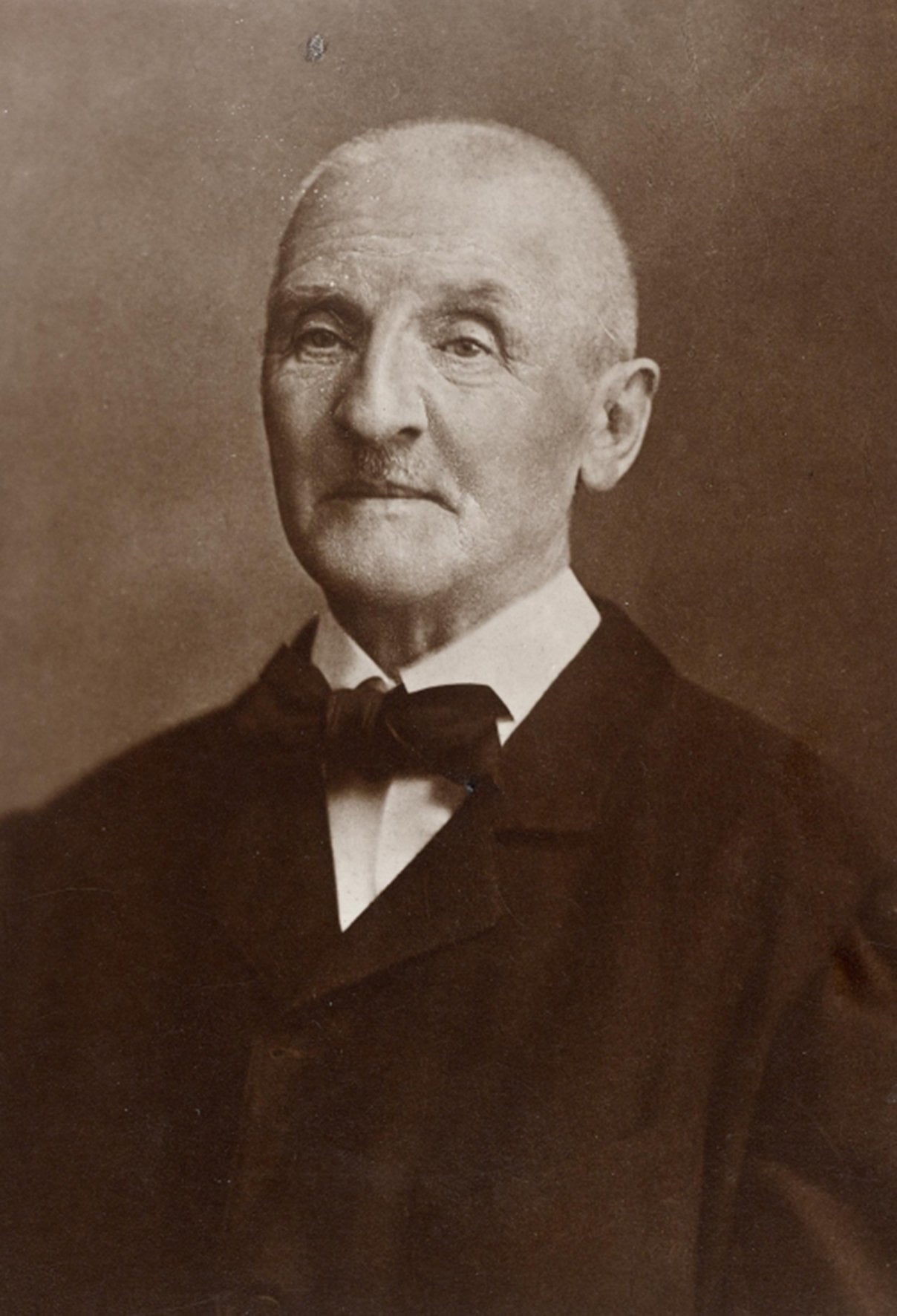

taken in Vienna in 1894

(Josef Löwy / public domain)

Yet for all its grandeur, Bruckner’s music making is not, at first hearing, easy on the ear, combining, as it does, the intricacies of the Baroque organ with the sensibilities of a man steeped in the harmonies and chants of the Church, yet fully cognizant of and familiar with the great orchestral possibilities of the late Romantic period, including the compositions of Richard Wagner. Nicholas Temperley, in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (1980), explains:

Some have classified him as a [musical] conservative, some as a radical. Really he was neither, or alternatively was a fusion of both. … His music, though Wagnerian in its orchestration and in its huge rising and falling periods, patently has its roots in older styles. Bruckner took Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony as his starting point.

From that starting point, Bruckner’s symphonies follow a consistent pattern, each one building on the previous one. Temperley writes that, as in Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9, a Bruckner symphony begins “mysteriously and climb[s] slowly with fragments of the first theme to the gigantic full statement of that theme” and includes an “awe-inspiring coda of the first movement.” Temperley continues with the Beethoven comparison:

The scherzo and slow movement, with their alternation of melodies, are models for Bruckner’s spacious middle movements, while the finale with a grand culminating hymn is a feature of almost every Bruckner symphony.

In that way, Bruckner employed the collective musical wisdom of the past with an intense and reverent appreciation, while creating something that Bruckner scholar Deryck Cooke called “a new and monumental type of symphonic organism … something elemental and metaphysical.”

Years ago, a music teacher I had in college expressed it this way: to begin to understand Bruckner, one must understand his brilliance and immersion as an organist and his mastery of counterpoint. At first listen, it may seem that his musical themes are disjointed, but upon repeated hearing, it becomes clear that each theme represents a part of his building edifice, essential segments of an immense cathedral of sound, intricately related in the final composition.

I distinctly recall hearing Bruckner for the first time as a young high schooler. It seemed like one giant mass of orchestral sound, every instrument performing at the same time, theme layered over theme—but missing those soothing, memorable, hummable “tunes” that you could hear in, say, Tchaikovsky, Chopin, or Johann Strauss Jr. Even so, despite my initial reaction, I knew there was something special there—a kind of irresistible and powerful movement, an immense and encompassing ambience that pulled me in and surrounded me and finally overwhelmed and convinced me. In particular, listening to the end of Bruckner’s very long Symphony No. 8—perhaps his most challenging—I was left perspiring and emotionally drained but also deeply, spiritually affected.

As I listened over the years to more Bruckner and read about his life and his conscious effort to utilize his music as a means to serve and honor God in a way that very few masters—either before or after him—have done, my understanding of his significance for our present culture grew as well. Despite the seemingly unstoppable modern currents in the arts and culture at the end of his life, Bruckner believed that the Great Tradition yet offered real and inexhaustible sustenance to those who would receive it. His role was to take those older forms, expand them to the very fullest, and reveal their continuing inspiration to Western society.

[Bruckner] lingers in opposition to the gangrenous and poisonous decay of Christianity, to the ravages of cultural decline and the corresponding triumph of cultural Marxism, which would sever the ties uniting us to our past and to memory.

The German-Austrian historian, Brigitte Hamann, in her superb volume Hitler’s Vienna: A Dictator’s Apprenticeship (1999), surveyed the intellectual milieu of the late Austro-Hungarian Empire and recounted the swirling turmoil that existed in Europe late in the 19th and early in the 20th centuries, with the advent of Communism and fascism, the birth of Freudian psychoanalysis, the burgeoning influence of “modernism” in the arts, and the liberal belief in the essential perfectibility of Man—all soon to be shattered by the experience of World War I.

That was the portentous world in which Bruckner lived, and that is why he was then, as he is now, a “sign of contradiction,” an overpowering reminder—difficult at times to fully absorb—of the still-unexhausted wealth of the old Western Christian (and European) heritage. He stands impressionistically athwart the seemingly irresistible modern idea of progress, the “movement of history,” so cultivated and celebrated today. He lingers in opposition to the gangrenous and poisonous decay of Christianity, to the ravages of cultural decline and the corresponding triumph of cultural Marxism, which would sever the ties uniting us to our past and to memory.

In his life, Anton Bruckner would have had no idea that he might ever come to symbolize such a contradiction to the age; indeed, a man of simple and direct faith, his objective was to glorify his Lord through the magnificent talent he had received. And this he did abundantly.

When he died in October of 1896, Bruckner was working on his ninth and ultimate symphony, the last movement of which he left only in sketches (in our day, there have been efforts to complete the work, based on his notes). Having earlier in life dedicated symphonies to the king of Bavaria and to Kaiser Franz Josef of Austria-Hungary, Bruckner said of his ninth symphony, “Now I dedicate my last work to the majesty of all the majesties, the beloved God, and hope that he will give me so much time to complete the same.” But the Almighty had other plans and called Bruckner to Him before the work was finished.

Famed conductor Hans von Bülow, who greatly admired Bruckner, once said of him that he was “half simpleton, half genius.” Bruckner, himself, described his role this way:

They want me to write differently. Certainly I could, but I must not. God has chosen me from thousands and given me, of all people, this talent. It is to Him that I must give [Bruckner] lingers in opposition to the gangrenous and poisonous decay of Christianity, to the ravages of cultural decline and the corresponding triumph of cultural Marxism, which would sever the ties uniting us to our past and to memory. account. How then would I stand there before Almighty God, if I followed the others and not Him?

In so living his life, Bruckner was one of the last great Christian paladins of the arts to engage the enemies of our civilization. Our culture is dying today for the lack of such giants.

It remains to make note of the essential recordings and editions. Bruckner wrote nine numbered symphonies; however, he also composed a “study symphony” (in F minor) while he was finishing his studies, in 1863. Another symphonic work, the so-called “Die Nullte,” or “No. 0” (in D minor), he withdrew, and it was not published during his lifetime.

There are literally hundreds of recordings of Bruckner’s symphonies and choral works available on compact disc, DVD and Blu-ray, as downloads, and incorporated into films. Because Bruckner was sensitive to the criticism of fellow musicians and continued revising his works until late in life, there are various versions and two major critical editions—one from the 1930s, by German musicologist Robert Haas, and one from after World War II, by Leopold Nowak—which makes selecting the best recordings of his symphonies somewhat complicated. At times, the differences between versions appear small, but some are more substantial.

Perhaps the best introduction to his work is a superb biographical film, The Life of Anton Bruckner (directed by Hans Conrad Fischer), available inexpensively from the Bruckner Society of America. A newly released Blu-ray Disc, Anton Bruckner: The Making of a Giant (on Arthaus Musik), offers details about his symphonic works. There are numerous DVDs of his symphonies, and it is impossible to proclaim just one of them the finest, much less to decide on a comparable CD incarnation. Of the more noteworthy are video performances under the direction of Sergiu Celibidache, Herbert von Karajan, Eugen Jochum, Günter Wand, Christian Thielemann, or more recently, Valery Gergiev.

Celibidache, of Romanian origin, has his strong partisans, and I confess that I am one. His performances are in most instances the longest, yet he never lets the attention or the frisson lag; he lets the music breathe until it is gradually sculpted into the grand artifice that Bruckner intended. There is an excellent box set of Celibidache with the Munich Philharmonic directing the sixth, seventh, and eighth symphonies on Sony, recordings of the fourth and fifth on the Arthaus, and of the ninth on Opus Arte.

Recently, the noted Russian conductor Valery Gergiev recorded, with the Munich Philharmonic, all nine of Bruckner’s numbered symphonies on both Blu-ray and DVD; the discs, a total of 10, are packaged in a handsome (but somewhat expensive) box, loaded with extras, including a hardbound book on Bruckner and his music (available on the Arthaus label). Filmed in the glorious Baroque nave of the historic St. Florian monastery, where Bruckner’s boyhood musical training began, the incredibly beautiful surroundings add to the power and grandeur of Gergiev’s performances (which are also available on CD on the Munich Philharmonic’s own label). Like Celibidache, Gergiev caresses Bruckner’s adagio movements, slowing them down to reveal their intricate beauty and deep spirituality.

playing an organ,

painted by Otto Böhler, c. 1914

(public domain)

The legendary Herbert von Karajan committed both the eighth and ninth symphonies to film, along with Bruckner’s heaven-storming “Te Deum,” now on Deutsche Grammophon DVD. And the internationally famed Brucknerian conductor Eugen Jochum is represented by a fine rendition of Symphony No. 7, on EMI. Continuing the long Germanic performance tradition, Günter Wand and Christian Thielemann also have video accounts available.

On compact disc, many musicologists point to the two complete cycles from Jochum, who was a Bruckner specialist par excellence. One was completed with the Staatskapelle Dresden (now very inexpensively out on Warner Classics), and a

second set is on the Deutsche Grammophon label with the Berlin Philharmonic and the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. Both sets reflect Jochum’s profound understanding of and identification with Bruckner’s deeply held faith as expressed in his music.

There are, of course, excellent performances of individual symphonies, one of which is Karl Böhm’s rendition of the fourth with the Vienna Philharmonic (1973). Then there are Jochum (with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra in 1964 and 1986) and Carl Schuricht (with the Vienna Philharmonic in 1963), both conducting the fifth.

Arguably the greatest conductor of the 20th century, Wilhelm Furtwängler, conducted Bruckner’s eighth in October 1944 with the Vienna Philharmonic in the

middle of a war zone—one can feel the Russians advancing on the city: the music is at times frenetic and gripping but always completely under Furtwänglers control. The sound is monaural and sometimes constricted, with the best incarnation coming in a box set (from the Music & Arts label) additionally featuring the great German director conducting the fourth (1951), the fifth (1942), the seventh (1951), and the ninth, also in October 1944, in Berlin, with Allied bombs faintly audible in the background.

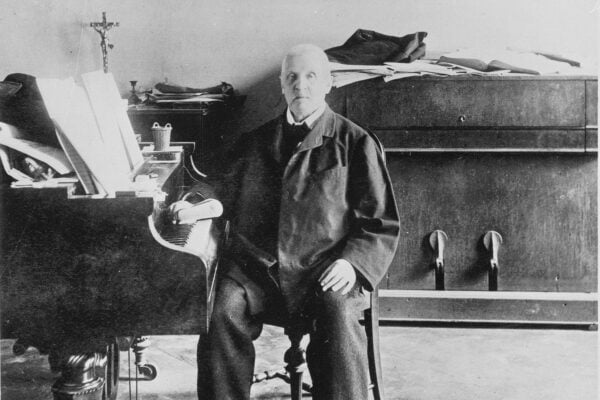

Top image: Anton Bruckner seated at a piano, circa 1892 (Austrian National Library)

Leave a Reply