There are many things I appreciate about Patrick Deneen’s book Why Liberalism Failed, but while Deneen’s study orbited around its topic and examined it in great detail, it never actually achieved escape velocity.

Deneen’s book showed all the ways in which he thought classical liberalism had formed and shaped the world against which he certainly wished to rebel, but in his conclusion, he acknowledged all the “achievements” of classical liberalism that he still wanted to keep and maintain—rights for women, to take just one example. Like a very young boy running away from home, he reconsidered when he reached the end of the driveway.

Despite this failure, the book still made a significant contribution—one that I appreciated very much—which goes to show yet again how every dark cloud has a silver lining. Deneen reminded me of something I always love to be reminded of, which is how much I hate social contract theory. His book also revealed (at least to me) the space that social contract theory has come to occupy in our political thinking. It is actually an origins myth.

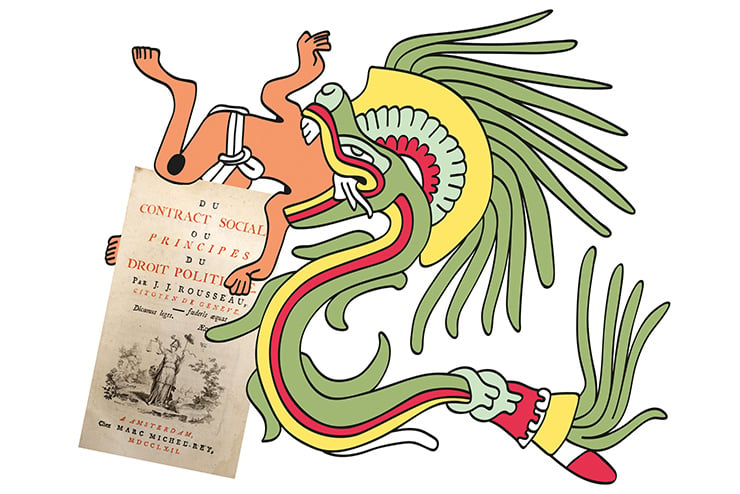

Every tribe has an origins mythology. The Babylonians have their Enūma Eliš, in which the god Marduk finally subdued the forces of chaos. The Cherokee believed that all animals were up in Heaven (Galun’lanti, meaning “beyond the arch”) but it got too crowded there. The earth was covered with water, so the animals sent down a water beetle who pulled up mud from the bottom of the sea to create the land, and then the wings of a great buzzard formed the mountains and valleys. Among the Mayans, seven deities, including the feathered serpent Kukulcán, formed human beings out of white and yellow corn.

However outlandish such stories might seem to us—and they are outlandish—they nevertheless present us with answers to very pressing questions that every social group must ask: “Who are we?” “How did we get here?” and “Where are we supposed to be going?” And then comes the question that is of the greatest practical importance: “How are we supposed to behave on the way?” As my son N. D. Wilson wrote in Notes from the Tilt-A-Whirl,

Every culture has felt the overwhelming pressure of existence itself and the need to explain it. There’s a sort of nervousness apparent in the myths of every people group, as if maybe we’re not supposed to be here and we all have to rehearse our story before the authorities come. ‘We’re sorry … there was this ice giant,’ we explain. ‘When Pangu died, we had nowhere else to go,’ we tell the cop.

As it happens, social contract theory has performed precisely this same mythological function for moderns. The ancient examples are defined by us as outlandish for various reasons, but right at the center of those reasons is the glaring fact that they are plainly superstitious legends—they didn’t actually happen. We think, and for good reason, that these myths should be relegated to the realm of retired superstitions because they did not actually occur. Who really believes that a feathered serpent ever did anything?

But the problem that confronts us in our air of vaunted superiority is the fact that the “social contract” never happened either. The whole thing is a thought experiment that somehow created obligations for everybody. This is a parliament that never met, voting on a bill that was never drafted—but only after serious debate among members who were never born.

The outcome of all these invisible civic forces moving about is that we—out here in the real world—are somehow under a solemn obligation to the state, which must not be questioned. The social contract is postulated as having authority because we needed some kind of authority in that space. This is the logic of idolatry, which is capable of creating any species of feathered serpent to fill the void. The void exists because as humans we need a foundation for our society—it is deep within our created nature.

The feathered serpent of social contract theory was born during the Enlightenment despite the fact that we all were already under a genuine social contract that actually did happen in history. God created and appointed two representatives of the entire human race, our first parents, and placed them in the Garden. He then told them that they must not eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.

This was not a tree that would provide our first parents with a basic understanding of morality, for if that is what it gave, then they could not have sinned by eating from it. They could do no wrong by eating from the tree if they approached it without any understanding of right and wrong.

Rather, throughout the Old Testament, knowledge of good and evil refers to the maturity and wisdom required by rulers, judges, and kings. Our first parents sinned by grabbing for such rulership prematurely. They were under an actual social covenant with God, but they wanted another one, with different terms. Their sin was to assume the prerogatives of rule for themselves, establishing their authority on their own terms and in their own name. This is precisely the thing that Enlightenment social contract theory seeks to do as well.

Every human society is a moral organism, and this means that every human society must make decisions that have a moral component. It therefore follows that every human society must give an account of the decisions it makes, not to mention the morality upon which those decisions rest. We are just now starting to realize how bankrupt the mythology of secular classical liberalism is, which is why someone like Deneen can cause quite a stir by pretending to challenge it. We are perhaps starting to realize that our feathered serpent is just like all the other feathered serpents.

Instead of an Enlightenment myth, we need a primal covenant that actually was made and understood by individuals who truly represented us, and represented us well. We have that in the Garden of Eden. Because we abandoned that, we had to make up an artificial substitute.

But we also have something else to deal with. We cannot appeal to the reality of this Paradise without also remembering that Paradise was lost to us. There was the Garden, but there was also the expulsion from the Garden. This means we must also remember our fallen nature. We have a social contract, but because of our sinful rebellion, that contract has been rashly broken.

Our created nature calls out for a societal foundation; our fallen nature does not want that foundation to be the Word of God. The fact that we spurn the Word—the Word that fashioned all the worlds—does not grant us the authority or ability to come up with our own mythical constructs. But we tried anyway. I am convinced that the reason social contract theory has had such staying power is because we instinctively realize that our only alternative is found in Genesis—and some of us fear that leaves us looking like fundamentalists, or naive little Sunday School kids.

So what happened was this: The 17th– and 18th-century Enlightenment social contract theorists—Rousseau, Hobbes, Locke—were men who were writing in the centuries just before Darwin. They could not have known that they were paving the way for him—but they most certainly were. The relics of the first Christendom still had an operational origins story.

For the Enlightenment thinkers, a replacement was an absolute necessity, and social contract theory was that perfect substitute. It met all the requirements: no God, no transcendence, and it never actually happened, making it impervious to historical investigation. The vote that occurred in this evanescent parliament was not subject to any demands for a recount. No scandal could bring this government down. A vote of no confidence was not possible because this was an ideal voting system for totalitarians—one in which no voting actually took place.

And as a consequence, a functionally atheistic society now had a philosophical basis for societal cohesion that the big thinkers could point to. And upon the publication date of Darwin’s Origin of the Species (1859), the rapid acceptance of the theory of evolution meant that the Judeo-Christian origin story underpinning Western Civilization, along with the societal cohesion it provided, had finally gone the way of the whistling wind.

We set up these golden calves at Dan and Bethel, and the lies worked for a time. But only for a time. As mentioned earlier, the basic questions are these: “Who are we?” “How did we get here?” and “Where are we supposed to be going?” followed naturally by the very practical question, “How are we supposed to behave on the way?”

If we reason from raw Darwinism alone, the answers to the first three questions appear to be as follows: “We are chance collections of meat, bones, and protoplasm;” “We evolved through blind processes of time and chance grinding away on matter;” and “Nowhere in particular.” All of these answers put an even greater weight on that last question: “How are we supposed to behave?”

The challenge of the last question for post-Darwinian moderns is that the meaninglessness of a Darwinian cosmos cannot be turned, by some magic trick, into a place where societies with meaning and purpose can thrive. In short, in reply to the question “how are we to behave?” the apparent answer now would be something like “to each his own.” Each individual bundle of nerve endings should do what seems best to him/her/it. But that answer, if given by everyone, would lead to societal chaos, at least according to those sentient bundles who had thought things through. To prevent chaos, the modern solons and poohbahs had to come up with a better answer to the question, which blind Darwinian science was unable to do.

What social contract theory allowed them to do—and it is remarkable that they have pulled it off for as many centuries as they have—is to act as though the question had been answered. And what it works out to practically is some form of utilitarianism—the greatest good for the greatest number, with “good” determined by our nonexistent parliamentarians. This worked only so long as the residue of the previous Christian consensus allowed everyone to define “good” in ways that were at least recognizable to the different perspectives involved in the discussion.

The fact that social contract theory exists off of the residue of Christendom forces us to look at all of this from another angle. The prodigal son did not run out of money his first weekend from home. He was enabled by his father’s money to live in a way contrary to his father’s values. The appropriation seemed to work just fine—until his inheritance was spent and gone.

There was a time when our secular establishment was able to buy drinks for the house and to proclaim that a common-sense approach to the common good was all we needed. But that was the father’s money talking. Now that we have squandered the moral capital we inherited from Christendom, we are discovering just how radically distinct the different modern ethical systems can be. At the American Founding, we were trying to navigate the differences between Presbyterians and Baptists, and at the outer edges, Quakers. Now we think it is possible to bridge the gap between gyrating drag queens at the children’s story hour and “black bumper” Mennonites. Some of us think that selling off the severed limbs of an unborn child is a constitutional right, while others think that our actual constitutional rights ought to be our constitutional rights. It is not possible to bridge the gulf between these viewpoints, especially not on the basis of a cooked-up 18th-century mythical origin story.

An old rhyme summarizes our dilemma quite well: “If wishes were horses, beggars would ride. If turnips were watches, I’d wear one by my side.” We cannot have a coherent political system simply because we have desperately wished for one. And we cannot fix that problem by imagining that our mythical ancestors had greater powers of imagination than we do. They did not.

Leave a Reply