One of the last great leftist myths of the 20th century is that the Spanish Civil War was a struggle of republican democracy against nationalist fascism. In reality, it was a violent mass-collectivist revolution put down by Spanish moderates and conservatives.

By the close of the 20th century, nearly all the great political myths and secular religions of the era had been discredited: anarchism, fascism, National Socialist racism, and Marxism-Leninism. In Europe only one survived in its classic form to undergo a major revival: the Spanish Civil War as a struggle of republican democracy against fascism.

During the past generation, the Spanish left has, under the old Popular Front banner of “Republican democracy,” tried to project their view of the Spanish Civil War as a sort of new founding myth for Spain, with the goal of either radicalizing the country’s present constitutional monarchy or replacing it with another extremist, Latin American-style republic.

The Spanish Civil War, better termed the Spanish revolution of 1936-39, was the only violent mass-collectivist revolution of the 20th century to take place in a Western European country. It failed for various reasons, but first of all because Spanish moderates and conservatives rebelled preemptively, before the institutional takeover by the revolutionaries could be completed. This left the revolutionaries with the dilemma of trying to carry out a violent revolution while also waging a full-scale civil war, something that proved beyond their powers.

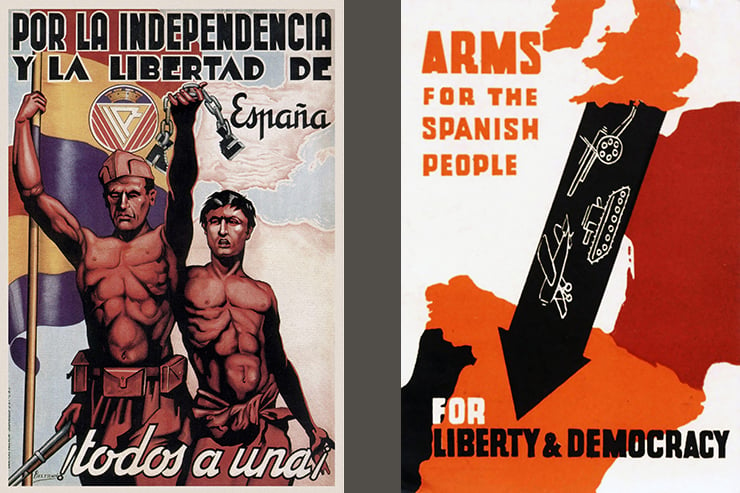

The Spanish Revolution was also unique in European history in being led by socialists and anarchists, while it was the Civil War itself that brought communism to the fore. From the beginning, Soviet leaders grasped that a new revolution in Western Europe had to be disguised as “republican democracy” to make it palatable to international opinion. Less than a year earlier, the Comintern had altered its own revolutionary approach, which had led to disastrous results in Germany, in favor of a new “Popular Front” alliance that could exploit Western democracy in the name of “antifascism,” the key new propaganda motif. Presenting the Spanish conflict as a struggle between “democracy and fascism” was a ploy that enjoyed considerable success, particularly among the Western intelligentsia, among whom a struggle against Hitler and Mussolini had become increasingly attractive.

For many complex reasons, the history of Spain has always been the most difficult to understand of any Western country. Its marked singularities and apparent countercurrents have understandably bewildered outsiders, which in turn helped the Popular Front narrative to assume a broadly accepted mythic form during the World War II era. This was further modified to present the Spanish struggle as the “beginning” or “opening round” of World War II, an equally extreme leap of the imagination.

As I began to study Spanish history in the 1950s, I realized that the more extreme aspects of the myth were exaggerated, but I nonetheless accepted the standard interpretation of the “democratic Spanish Republic” and its at least semi-democratic left. There was no serious scholarly literature to the contrary. Moreover, my first two books on Spanish affairs dealt with key forces of the right, first the fascistic Falange (Falange: A History of Spanish Fascism, 1961) and then the military (Politics and the Military in Modern Spain, 1967), which were enthusiastically received by reviewers, most notably those on the left.

It had not been my idea to investigate the revolutionaries. The suggestion came from Jack Greene, the Americanist historian at Johns Hopkins University, who, amid the “history boom” of the 1960s, was editing a 10-volume series on revolutions in the modern world. He invited me to write the study on Spain, and, after some reflection, I accepted. The research that I conducted on the Spanish left between 1966 and 1968 constituted a “before-and-after” moment in my understanding of recent Spanish history. I was quite surprised to find that the Spanish left were not the bumbling, well-meaning reformists that, according to the myth, they were supposed to be, but rather that they were determined, de facto authoritarians whose revolutionary sectors had dedicated themselves with ever-increasing violence to a direct assault on Spanish institutions.

This research eventually became The Spanish Revolution (1970), my study of the revolutionary left in Spain from their origins to their final defeat, in 1939. Though some of the book’s interpretations have required revision after the opening of new archival materials, particularly in the former Soviet Union, it remains the only one-volume study of the entire revolutionary process in Spain in any language. The Washington Post’s “Book World” named it one of the 50 most outstanding books of 1970, and, as Spanish censorship eased, two different Spanish translations appeared during the following decade. But leftist commentators, who had hailed my first two principal Spanish books, were sometimes scathing with regard to The Spanish Revolution, which dared to expose the established myth.

The 1970s were a decade of dramatic transformation in Spain, which launched its latest countercurrent initiative when, at the height of the final phase of communist expansion in the Cold War, it underwent a startling regime change to liberal democracy, helping to initiate the 20th century’s last great wave of democratization. This would last, in Spain and in the world, through the 1990s. Censorship ended, and an avalanche of attention to contemporary history ensued, but the new spirit seemed to want to bury the past, as far as partisan politics were concerned, leaving history to the scholars.

Or so it seemed. What was really happening was that the “New Left” generation of the 1960s had already begun to establish itself in Spanish universities, even under an increasingly tolerant Franco regime, and the movement soon extended its domination in Spanish academia. Moreover, moderate and conservative political interests showed surprisingly little attention to culture and to recent history, living as they were in perpetual fear of being called “Francoists,” so that by the last years of the century, leftist control of media, culture, and education was even more complete in Spain than in some other Western countries. Certain topics and themes became taboo even though a basic freedom of speech continued to exist in the country as a whole.

The resulting dilemma was exemplified in the career of Javier Tusell, Spain’s leading political historian of the late 20th century. In 35 years, he turned out some 20 books, all of high quality and most based on original archival research. But to maintain a freedom for objectivity and critical interpretation while remaining in the good graces of his colleagues, Tusell devoted himself primarily to studies of the Spanish right and never undertook a major critical study of any aspect of the left. Thus by the 1990s, historiographic conformity to the myth of the Republic and Civil War was almost complete.

Amid this intellectually stagnant situation, there suddenly appeared in 1999 a work titled Los orígenes de la Guerra Civil española (“The Origins of the Spanish Civil War”) by a completely unknown author—Pío Moa. He was not an academic but an independent scholar, the kind of figure somewhat more rare in Spain than in the English-speaking world. Moa was a repentant Marxist who had begun adult life as an active member of the Revolutionary Antifascist Patriotic Front (FRAP), a 1970s revolutionary terrorist organization that had fought Spain’s democratization tooth and nail. In the years that followed, he devoted himself to prolonged study and reflection concerning his country’s history. After two decades, Moa reached conclusions widely at variance both with his own early convictions and with the conventional myths concerning recent Spanish affairs.

Los orígenes, Moa’s first book, took direct issue not with myths about the war itself but with standard ideas about its background, exposing the “origins” of the conflict in 1933 and 1934 as the left first sought to impose an exclusivist system and then, having failed, turned to multiple revolutionary insurrections, climaxed by the violent Socialist assault of 1934. Moa had written the most dramatic and original work in recent Spanish historiography and quickly followed it in 2000 with Los personajes de la República vistos por ellos mismos (“Leaders of the Republic as Described by Themselves”), an eye-opening portrait of the key leftist leaders as painted by their own original and acerbic descriptions of each other. Then, in 2001, came El derrumbe de la segunda república y la guerra civil (“Collapse of the Second Republic and the Civil War”), which treated in detail the climax of the Republic’s revolutionary process and the beginning of the war. Spanish readers responded enthusiastically, all the more because Moa showed not merely analytic daring and originality but also unusual literary skill, which was the more notable because of the clumsy, torpid, and self-absorbed expression of so many Spanish historians.

Moa outraged the leftist professoriate, however, and its seemingly unanimous chorus of denunciation intimidated anyone who might have dared to say a word in his favor. What was remarkable about the deluge of abuse was that serious discussion or criticism of his emphases and interpretations was virtually nonexistent. Criticism focused, in typical Spanish style, on ad hominem attacks. This abuse especially emphasized Moa’s lack of academic credentials, most commonly insisting that only a “professor” could produce valid historical work. Such an argument is the more preposterous when one considers that most Spanish history professors are little more than time-serving bureaucrats who produce scant—and sometimes no—historical publication.

Moa came to occupy a unique position—the country’s most widely read historian nonetheless living in permanent ostracism from the university system and the establishment media.

The climax of Moa’s early work appeared in 2003, when a leading trade publisher, La Esfera de los Libros, brought out his Los mitos de la Guerra Civil (“The Myths of the Civil War”). It was Spain’s nonfiction sensation of the year, eventually selling more than 150,000 copies, indicating a thirst by Spanish readers for critical history willing to break the mythic taboos.

Since establishment media and academic publications generally ignored Los mitos, Álvaro Delgado-Gal, the astute editor of Revista de Libros, the country’s leading book-review journal, decided to break the boycott of silence by seeking a non-Spanish historian to review the book. He invited me to undertake the task, and I responded with alacrity.

My review highlighted key issues on which Moa offered trenchant analyses and significant new interpretations based on convincing data. While several of Moa’s interpretations could be questioned, it was the responsibility of serious scholars to debate or rebut the disputed issues rather than to impose a priori censorship. My conclusion was that the book, even if imperfect, was a major contribution to discussion of the Civil War.

Santos Juliá, arguably the leading Socialist historian on this topic, was asked to reply. He merely repeated the line that Moa was beyond the pale and even threatened my “expulsion” from the guild of professional historians for daring to suggest that the subject merited honest debate.

Los mitos de la Guerra Civil was not another general history but a study of key personalities and issues that in the standard leftist interpretation had been variously mythified, demonized, or simply misrepresented. The book devoted individual chapters to 10 of the leading figures, offering incisive discussions often at wide variance with the standard accounts. The main part treated 17 key issues or aspects, such as the effect of “arming the masses,” creating “the first air-lift in history,” “the greatest religious persecution in history,” several of the greatest atrocities or alleged atrocities, shipment of the Spanish national gold reserve to Moscow, the character and role of the International Brigades, several of the most important battles, intervention and nonintervention, and the policies and roles of the two decisive leaders: Popular Front Prime Minister Juan Negrín and Nationalist General Francisco Franco. The book concluded with an examination of the place of the Civil War in Spain’s history and in its historiography.

Moa’s book was unique in adopting a thematic and problem-oriented approach and in aggressively confronting the dominant myths. Due to its interpretative thrust, the effect was polemical, even though the individual analyses were carefully reasoned in his typically lucid, often eloquent, prose.

at a book signing in Madrid in 2010

(Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0)

Moa came to occupy a unique position—the country’s most widely read historian nonetheless living in permanent ostracism from the university system and the establishment media. In other countries, non-academic historians sometimes achieve venerable positions, most normally for expressing approved pieties about the national past. Moa, conversely, became very nearly a one-man movement taking on the national leftist establishment by offering independent accounts and interpretations of major historical problems. His endeavor has almost inevitably involved an increasingly polemical approach, a lonely enterprise requiring impressive personal stamina and moral courage.

Historical knowledge is advanced primarily in two ways: the standard route is through new primary research; the less frequent but more intellectually challenging is the reexamination and new analysis of previous work. Only a minor share of Moa’s output is based on primary research, for the greater part deals with the reexamination of existing materials that have been either ignored or deliberately distorted in preceding accounts.

Moa remains a prolific scholar and writer who, in the past two decades, has produced numerous works that also treat broader historical themes, most notably his impressive account of La Reconquista y España (2018), as well as two novels and volumes of essays on diverse topics. It is probably accurate to say that he has played a more important role in the cultural and intellectual life of his country than any other independent scholar elsewhere, though he will always remain an historien maudit (“cursed historian”) to Spain’s benighted cultural establishment. There remains a tiny handful of professors in Spanish universities who do serious independent and objective work and who make major contributions, but they have to be very careful to avoid the most controversial approaches.

In my own work, I returned to the subject of the Spanish Civil War around the time that Moa began to publish. My initial motivation was to make use of new material from the Soviet archives to finally make clear the Soviet and Communist policies in Spain, a subject that had always aroused controversy. Six years of research eventually became The Spanish Civil War, the Soviet Union, and Communism (2003), after which I followed up on José Ortega y Gasset’s dictum of 1938 that the most important thing to know about the Spanish war was “how it began.” This investigation led to The Collapse of the Spanish Republic, 1933-1936: Origins of the Civil War, which Yale University Press published in 2006. Several other studies on diverse aspects of the war followed in the next few years, climaxed by my relatively brief book The Spanish Civil War, intended as an analytic summary for new readers and published in 2012 by Cambridge University Press as an entry in its “Essential Histories” series.

My other concluding work in this area was an effort to place the Spanish revolution and civil war within its proper historical context. This context was not World War II, in which Spain was not a belligerent, but rather the revolutionary civil wars of Europe in that era. I summarized this analysis in my 2011 book, Civil War in Europe, 1905-1949.

During the 21st century, the politicization of history has played a greater role in Spain than in any other Western country, for nowhere else (at least until 2022, in Russia) has government proposed specific national censorship laws governing the discussion and interpretation of recent history. The first Spanish Socialist legislation of 2006 went no further than state subsidies for proselytizing certain approved versions of history; the new proposals, championed since 2017, mandate direct suppression, terms of imprisonment, and large fines. It has not yet been possible to find the votes for final approval of this Stalinesque measure, but once more, as on so many other occasions since 1821, the Spanish left has sought to take the lead in political radicalization within Western countries.

Leave a Reply