“On the whole, the home remains the supreme cultural achievement of women.” -Georg Simmel

Elisabeth Griffith: In Her Own Right: The Life of Elizabeth Cady Stanton; Oxford University Press; New York.

Kathleen Brady: Ida Tarbell: Portrait of a Muckraker; Seaview/Putnam; New York.

Near the turn of the century Charles Peguy, alarmed by the advance of secularism in the modern world, predicted that the true revolutionaries of the 20th century would be the fathers of Christian families. Today we might fairly turn Peguy’s aphorism on its head and say that the true radicals at the moment are the mothers of Christian families. So insistent and pervasive has the feminist drumbeat become that it is very nearly the con ventional wisdom that any social distinction between the sexes is the result of pernicious “sexism,” which is as unjust, if not more so, than racism.

“Stanton’s hammering at all the ways men have subordinated women antici pated by a century the female conscious ness raising adopted by women’s liberationists.”

The New York Times Book Review

Women still marry and start families, yet motherhood is no longer viewed as the most important thing a woman can do in her life. Motherhood, instead, is viewed as simply one “option” among many, or perhaps as a single facet to be “integrated” into the “life-style” of the thoroughly modern woman. We should not be surprised, then, that feminist agitprop attaches an implicit stigma to motherhood, a veiled yet deliberate assault on the self-esteem of those women who choose to be “mere” mothers.

Here and there the feminist rage against human nature has broken out into open denunciation of mother hood—as it must if it is to remain consistent with its own logic. More than a century ago, Elizabeth Cady Stanton forthrightly declared that marriage, a “man-made institution,” was inherently degrading to wom en, and that “this marriage ques tion lies at the very foundation of all progress.” But Stanton was no matri monial Luddite; she defended monog amous marriage on other occasions and advocated legal reforms which by today’s standards seem reasonable and just. Still, Stanton understood the tactical utility of rhetorical extremism, for, by the Law of the Slippery Slope, the outrageous eventually seems reasonable.

The pentecostal moment for the American feminist movement oc curred at Stanton’s home in Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848. Even though the moderate political reforms demanded by the Seneca Falls sisters—divorce law reform, women’s suf frage, etc.—were many decades in coming, the dilemmas of feminism were apparent in the lives of Stanton and the early suffragists. Stanton, ac cording to her biographer, found her children “a source of enormous satis faction,” yet wrote to the unmarried Susan B. Anthony on more than one occasion that she longed to be free of both her husband and the kids so as to devote more time to the cause.

Stanton did not live long enough to see women receive the vote, but later in life she achieved independence and celebrity status. She spent eight months a year for 10 years speaking publicly on the Lyceum circuit, stayed with prominent citizens at her various destinations, and earned for herself the title “the Grand Old Woman of Amer ica” by the newspapers. Toward the end of her life, Stanton professed some self-satisfaction at having become the first of the “new women,” a type with which we have become all too familiar in recent years. (Indeed, Stanton might well be characterized as “the Bella Abzug of the 19th century.”)

Yet a critical look at Stanton’s life reveals the paradoxes, ironies, and contradictions of feminism. Like so many modern enthusiasms, feminism begins as the domain of the very affluent. The Cady household where Stan ton was raised employed 12 servants, and later in life Stanton retained a household staff which gave her the freedom to pursue her public interests. (Her biographer does not record whether the domestic staff was composed of men or women.)

The sustained rise of American liv ing standards over the last century has, it goes without saying, broadened op portunities for everyone, especially women, who are no longer bound to domestic duties by necessity. There is no disputing that the changes of socie ty wrought by modern economies have affected relations between the sexes. I doubt whether Mrs. Jerry Falwell or Phyllis Schlafly would stand for the domestic regimen of their grand mothers.

But this presents us with one of the grand ironies of America. America is the arena in which true progress is vindicated; yet even as progress has expanded opportunities and secured a broader range of rights, the feminist rage against our liberal society has grown more strident and uncompro mising. Only in America, it seems, do women recognize how bad off they are!

Stanton’s case aptly illustrates the degeneration of feminism from its ori gins with Anthony and the early suffra gists. Many of the early suffragists were scandalized by Stanton’s more outra geous dicta, many of which could have come from today’s stentorian feminists: “Society as organized today under the man power is one grand rape of womanhood.” Yet the femi nists of Seneca Falls, Stanton includ ed, made an explicit appeal to natural rights as the basis of their concrete political demands, and even fashioned their “Declaration of Rights and Senti ments” after that classic embodiment of natural right, the Declaration of Independence.

This appeal to natural right is ironic, for contemporary feminism, like most other modern ideologies, begins with an explicit denial of human na ture. Nature is a term of distinction, which, as well as providing the basis of man’s inherent rights, also sets limits to what man may aspire to do. Femi nism shares with modern scientism the fallacy of supposing that because ne cessity has been mitigated by material progress, nature, especially human na ture, is therefore malleable to man’s will.

While the Stanton of Seneca Falls appealed to natural right as the basis of political equality, the older Stanton understood that nature has to be reinterpreted—denied, in fact—for the more radical feminist claims to social equality to have any plausibility. Stanton aimed high, writing The Women’s Bible in 1895, which pro fessed an androgynous “Mother and Father God.” On another occasion, she even came close to suggesting that women could be the physical equal of man through “the healthy develop ment of their muscular system.”

The tacit assumption behind the feminist blast at the “patriarchal” so cial order is that there is really nothing prescriptive about human nature, and that our social ordering is merely an accumulation of “roles” imposed by illegitimate tradition or force. Hence the heavy emphasis today on new “role models.” Elisabeth Griffith explains in a “methodological note” that “role models were central to the develop ment of Elizabeth Cady Stanton as a feminist.” Three times in 30 pages Griffith laments that Stanton’s greatest hindrance at the moment was that “she was without a role model.”

This preoccupation with “role mod els” reveals the biases of feminist biog raphy: their polemical intention is made clear by the hindsight interpreta tions which judge these 19th-century subjects by today’s standards. In this crucial respect these biographies tell us more about the biographers than the subjects. Consider the closing para graph of Kathleen Brady’s portrait of Ida Tarbell:

“In life she had never found repose. As a woman in a male world, she felt herself so inferior, especially when glimpsed from the height of her dreams, that she dared not face many aspects of herself. Ida Tarbell was not the flinty stuff of which the cutting edge of any revolution is made. She was a reasonable woman who thought she tried to accommodate herself to circumstances, not to change them. Yet she was called to achievement in a day when women were called only to exist. Her triumph was that she succeeded. Her tragedy was never to know it.

Now this might be true, but it is not established by Brady’s narrative. The fact is, Tarbell didn’t fit the feminist “role model” of a woman whose “con sciousness” had been “raised”; she “was not the flinty stuff of which the cutting edge of any revolution is made”; therefore, there must be some thing lacking in her that kept her from facing ”many aspects of herself.”

“In the end, lofty and largely

isolated from the groups

speaking in her name, [Stanton) nearly approximated the an drogynous deity which was the only

one she deigned to recognize.”The Progressive

What disappoints feminists about Tarbell is what also disappoints them about women of distinction today like Margaret Thatcher, Jeane Kirkpatrick, and Sandra Day O’Connor: they don’t toe the feminist line. (The rabid Sonia Johnson calls Kirkpatrick and Thatcher “female impersonators.” Get it: it’s not physiology that matters, it’s your “consciousness.”)

Tarbell, although she was comfort able in the company of men, never married and had little romancein her life; she was extremely dubious about the suffragist movement and the femi nist agitators of her day. Even though she had broken clear of “woman’s traditional place,” she nevertheless up held the value and importance of do mestic life for women. Tarbell had no enthusiasm for the vote, and doubted,according to her biographer, “that women would use their ballot any more wisely than men.” Indeed, in 1928,Tarbell blamed Al Smith’s loss on the women’s vote (the first “Gender Gap”?). When the 19th Amendmentfinally passed in 1920, a suffragist told Tarbell: “The millennium has come. You’ll see what a world we will make.” Tarbell knew better, perhaps anticipat ing the Ferraro campaign: “Women will not find themselves in the political field in less than fifty years.”

Aside from the hidden feminist ax grinding quietly in the background, this is a fine biography, providing rich details about the journalism of the time and other major figures including Lincoln Steffens, Samuel McClure (founder of McClure’s Magazine), John D. Rockefeller and his Standard Oil, and many others. Brady explores the possibly vindictive motives behind Tarbell’s drive to write her expose of Standard.

But Tarbell was more than a female Woodstein; she wrote creditable biog raphies of Lincoln, Napoleon, and Madamede Roland, was asked repeat edly to serve the government (she usually declined), and displayed good sense about many of the issues of her time. She thought Henry Ford’s World War I “peace ship” idea was ridiculously naive, and though she regarded herself as “progressive,” she resisted ideology. Unlike Steffens, she did not see mendacity at work everywhere, and she never regarded socialism as the magic cure for man’s ills. Arguably the only times she allowed righteous indignation to erupt into excessive zeal were in the cases of Rockefeller and the tariff question.

There is no doubt that Tarbell was insecure, especially about money, and was uncertain of herself at various turns in life. Still, she had many virtues; she was modest, fastidious, and charitable. Perhaps she had regrets later in life that she hadn’t followed her own advice to other women to marry and pursue domestic life. Yet compared with Stanton, Tarbell’s is indubitably the greater achievement. Still, Brady leaves the impression that the correct “role model,” as far as one’s “consciousness” goes, is Stanton. Like so many biographers, Brady tries to understand Tarbell better than Tarbell understood herself, and in doing so succeeds only in revealing the biases of our own time. cc

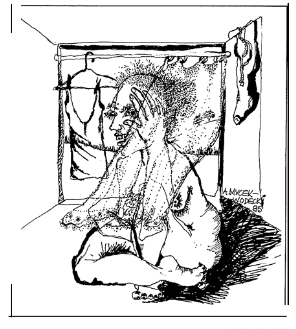

Image Credit: Comparable Worth?

Leave a Reply