Frances Spalding: Vanessa Bell; Ticknor & Fields; New York.

Karen Monson: Alma Mahler: Muse to Genius: From Fin-de-Siecles Vienna to Hollywood’s Heyday; Houghton Mifflin; Boston.

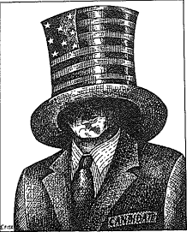

Women are in many ways the bearers and keepers of culture. However excluded they may have been from be coming artists in their own right, women throughout history have shown a remarkable capacity for surrounding themselves with art and for creating an environment in which art can flourish. From the wives of Roman patricians to the bustling patronesses in their salons during the last three centuries, art and ideas have found hospitality and thrived. Like any good thing, however, the relation of women (and men, for that matter) to art has its characteristic perversion. In a secularized society, art easily becomes a substitute for religion, an end in itself rather than a means toward the enhancement of the human spirit. Art can even become a substitute for life, acting as an emotional crutch that provides an escape from the daunting realities of daily life. For Vanessa Bell and Alma Mahler the life of art may have been a vocation, but it also acted as insulation, shielding them from both their personal anxieties and from the harsh and confusing events of the 20th century. Art for art’s sake has always produced a curiously enervated and often trivialized sensibility; neither Vanessa Bell nor Alma Mahler escaped from this condition.

Long after they initially came together, those forming the Bloomsbury set hovered around Vanessa Bell, biographer Frances Spalding says, “attracted by the atmosphere of tolerance and freedom which, with her easy control over domestic matters and her scorn of accepted conventions, she helped to create.” Even more than her painting, Spalding celebrates the domestic calm which Vanessa carried with her to Sussex, France, and to the elegant Georgian squares of Bloomsbury. Although she appeared to be a low-key matriarch and a spurner of conventions,Vanessa Bell led a life replete with ironies and contradictions to which Spalding appears oblivious. The mythology connected with the Bloomsbury Group has clouded the historical record. When its critics accuse Bloomsbury of a virtual monopoly on the discussion of ideas during the first half of the century, Bloomsbury’s defenders fume impatiently, arguing that a small group of private individuals who never sought public office could hardly be termed a conspiracy. The truth lies in between.

Bloomsbury liked to think of itself as a small enclave of culture in the midst of boors and barbarians, a gnostic group of unconventional people who were far ahead of their time. In fact,they were as much creatures of their time as anyone could be. Before the British Empire collapsed, the British spirit had already done so. Without the moral and historical sense which the older generations had taken for granted, the young began to cringe before the confident, public, duty-oriented Edwardians. As historian Paul Johnson notes in his Modem Times, the new spirit was epitomized in the secret, elite society at Cambridge University known as the Apostles, who were diffident, retiring, unaggressive, agnostic, and critical of grandiose schemes; more concerned with personal than public duties, they cultivated introspection and friendship. Its philosophy came from G. E. Moore’s Principia Ethica, which extolled hedonism based on friendships, and its propagandist was Lytton Strachey, whose Eminent Victorians vilified the Blimps and Grundys of Victoria’s reign. The homosexuality and pacificism of Bloomsbury were retreats from the challenges of affirmation, sacrifice, and commitment. It was, above all, Bloomsbury’s corrosive cynicism that provided relief to those who couldn’t support British institutions; the cynical climate of ideas which blames “conventions” as obstacles to the good society is a legacy which is very much with us.

Vanessa Bell embodies the paradoxes of Bloomsbury: she was as much a creature of late-Victorian culture as she was of the avant-garde. She and her sister, Virginia Woolf, were daughters of Leslie Stephen, the biographer and historian of ideas. In his home, both Vanessa and Virginia had the leisure and the encouragement to develop their respective artistic skills. Stephen was a pampered man, and he needed women to soothe and take care of him–first his wife, and after her death, his eldest daughter, and when she died, Vanessa. Though she may have loathed the tiring responsibilities of hostess, Vanessa remembered her parents’ lawn parties with artists and writers, and the joys of family life; she was to pattern her whole life around them. Vanessa Bell scorned marriage, but as Spalding notes, she was “voraciously maternal,” perhaps in compensation. Stephen’s frugality also enabled him to provide his daughters with money. Like her Bloomsbury associates, Vanessa never lacked; their wealth and connections helped to keep them insulated from the outside world.

As a painter, Vanessa rebelled against the traditional “Academy” type of realism, which had degenerated into a dull assimilation of tired formulas. Like many of her peers, Vanessa also detested the “literary” or “narrative” art which the British were fond of, and held that art need neither teach nor improve to be valuable. For a times he came under the influence of John Singer Sargent, but the most lasting influence on Vanessa was the Post-Impressionists, who shocked the Edwardians when they viewed the major show arranged by Roger Fry in 1912. What appealed to her was the use of color and of underlying form to construct space and bring out relationships. Most of Vanessa’s early work is clearly derivative, employing the stock subjects, such as bathers or haystacks.

The horror of World War I caused British artists to forsake abstraction and to return to representational art. But the war hardly touched Bloomsbury: the men became farm laborers to avoid conscription, and simply ignored the carnage. Vanessa’s personal life in the following years was to manifest an emotional uncertainty that is reflected in her paintings. Her marriage to Clive Bell was soon over: essentially a light weight, impresario of art, he could not hold Vanessa’s attention. A short affair with Roger Fry, a more intellectual impresario, could not be sustained because his aggressive, fast-paced life conflicted with her desire for a static existence. Her love for the homosexual artist Duncan Grant could never be returned, but she clung to him and looked up to him as a Master, all the time deprecating her own talents. Ultimately, this apparently unperturbable matriarch was a deeply insecure woman, emotionally dependent on her children and the man whom she considered a genius.

Vanessa Bell and the other Bloomsbury artists illustrate T. S. Eliot’s concept of the “dissociation of sensibility,” the disjunction between head and heart. Vanessa practiced the Bloomsbury penchant for “detachment,” a corollary of its supposed freedom from illusions. One of the results of this is evident in a painful, late self-portrait which reveals the unfulfilled old woman.

In addition to painting, Vanessa’s other achievement is in the decorative arts, stemming from her work with Roger Fry’s Omega Workshops and her lifelong collaboration with Duncan Grant. Here again, Bloomsbury paradoxes abound: the socially progressive set practicing the most bourgeois of art forms, decorating fabrics, dinnerware, and the walls of the well-to-do. In these designs “detachment” is thrown to the winds: they are light and rhythmic, often in soft pastel colors–an obvious reaction against the heavy reds and blacks of a late-Victorian childhood. The Omega Workshop, in effect, is the direct ancestor of the sheet and pillowcase department at Bloomingdales.

Vanessa Bell had a simple dignity about her, so that even in her gypsy-like, casual appearance, she carried herself with a natural grace. Alma Mahler was always a sophisticate by comparison, “the most beautiful girl” in turn-of-the century Vienna, when it was the cultural capital of the world. Alma Mahler had something of the “grand lady” about her throughout her life. Except for a few songs written while she was a music student, Alma Mahler produced no art. But like Vanessa Bell, she was drawn to artistic circles and provided an atmosphere of feminine hospitality and stimulation which made her company itself desirable. The subtitle of Karen Monson’s biography reveals the book’s raison d’etre: “Muse to Genius.” The story of Alma Mahler would, it seems, be about the grand lady of culture, whose beauty and vivacity inspired a dozen of Europe’s greatest artistic geniuses, and whose passions and sufferings are a testament to an intensely lived existence. Unfortunately, when the facts are presented, the reality is rather more sordid.

Daughter of the successful landscape painter J. E. Schindler, Alma had all the advantages of Leslie Stephen’s daughters. She was an industrious music student who managed to captivate (though not through music) the director of the Vienna Opera, Gustav Mahler, who pursued and won her. Mahler’s single-minded devotion to music was hard on Alma, though later in their marriage he recognized this and made a gallant effort to make amends. Sadly, Alma never understood her husband’s music, and during their marriage she began a life long habit: convincing herself that she would be happy with some man other than the one she was with. After Mahler’s death the painter Oskar Kokoschka became her lover, and when she became pregnant by him, she aborted the child. She sought out the architect Walter Gropius, the founder of the Bauhaus–whom she had been tempted to have an affair with while still married to Mahler–married him, and left him about a year later for the young poet Franz Werfel. Even with Werfel, the author of once-popular novels like The 40 Days of Musa Dagh, she wondered whether she wouldn’t be happier with Kokoschka after all. In the years leading upto World War II, Alma’s anti-Semitism became more pronounced, causing her to be exceedingly ambivalent about her marriages to two Jews, Mahler and Werfel. Alma quickly became a fascist by conviction, though not an activist. Driven to exile by the war, she and Werfel went to California, where he died in 1945. Alma stayed in America, and died at age 85.

This summary of Alma Mahler’s life is somewhat brutal, emphasizing many of the least attractive facts of her life; nothing is said of her commitment to art, her capacity for genuine love, the exuberance which led Kokoschka to call her a “wild brat” on her 70th birthday. All of these traits were real, and deserve to be remembered. But like Vanessa Bell, Alma Mahler wandered through the 20th century, clutching to herself the art which couldn’t rid her of her problems. That her life story should be told and reflected upon is fair and praiseworthy; that the moral drawn from that story is a sentimentalized paean to the “muse of genius” is not.

Leave a Reply