“Men ambitious of political authority have found out the secret of manufacturing generalities. “ -Sir Henry Sumner Maine

Donald Lambro: Washington—City of Scandals; Little, Brown; Boston.

Richard E. Morgan: Disabling America; Basic Books; New York.

The contemporary American political scene does not encourage optimism. Donald Lambro, author of Fat City, documents in minute detail the all-too-numerous Washington scandals. He describes the unearned rewards secured by persons and groups possessing the necessary clout and connection, as well as the fate of the occasional dissenter. Richard Morgan describes the even more ominous invention of “rights” supposedly based on Constitutional interpretation. These rights, which always strengthen the claim of the individual against the community, were conjured with little regard for history, the intent of Congress, the interests of the community, or the precepts of order. In essence, both books describe the malaise of the American political process—the corruption of government via special interest groups.

Why has the contemporary Ameri can political system proved to be so vulnerable? To some degree, the problem stems from the liberal Lockean origin of our polity, which defined society as a conglomeration of atomized individuals who live together in order to promote their personal interests. Old liberals had little concern for the common good but instead a faith that the competing interests would somehow achieve a balance. The system worked so long as the very secular liberal perception was underpinned by a strong Protestant ethos that stressed work, duty, and honesty. Historically, the system also benefited from its geo graphical distance from Europe, its abundance of natural resources, its cultural homogeneity, and good for tune. Compared with other societies, America was seldom challenged by real adversity.

A society so hazy in its conception of the common good and so optimistic about countervailing power as a deterrent to abuse is especially vulnerable to those special interest demands documented by Lambro. The decline of the Protestant ethos—especially among the elites—removes previous restrain ing influences. Without a clear sense of distributive justice, there are no norms by which we can judge the demands of an organized group. The result is, everyone demands the ultimate. One gets what one can; every one is doing it. Anything is acceptable so long as it does not violate the letter of the law. Eventually, the unorga nized and the unpolitical must pay the price.

The liberal faith in countervailing power as a remedy for extravagant special—interest demands has proved delusive. Often there is no countervailing force. An explosive current ex ample would be illegal immigration. Liberals who can never say “no” to an ethnic minority join hands with those who want cheap labor in opposing control over our borders. The com mon good is ignored as we cooperate in flouting the law and in building a nation within the nation, irrespective of future costs. At a lower level, the farm lobby is seldom confronted by an antifarm lobby, the military-pension lobby is seldom confronted by an anti military pension lobby. In these and other areas the national interest is left to shift for itself, and the public is expected to pickup the tab.

Even more dangerous than the Washington scandals are the inven tions of the “rights industry.” These activities tamper with the very fabric of the Constitution. The Constitution and the English language serve to hold together a potentially divided society. But why should the individual be bound by an 18th-century document designed by 18th-century aristocrats to promote their concerns? At what point was consent given? Few contemporary Americans even had forebears in 18th century America.

The national myth works so long as there is popular veneration of the Con stitution. But those who would again and again subvert the document by squeezing out of it “rights” that have no historical basis succeed in compromising the myth. There is the danger that at some point the average citizen will lose his reverence for the founding contract. The emperor will stand naked and unloved. As Burke warned, compromising the traditional systemic myths can leave a vacuum filled ultimately by the policeman. Recent examples of middle-class citizens appeal ing to nonpositive higher law to smuggle in aliens, to bomb abortion factories, and to inconvenience sub way thugs may be a harbinger of the future.

To understand Morgan’s “rights in dustry,” we might repeat the old Leni nist question: Who stands to gain by this? Is it the politicians, the ideologues, the bureaucrats, the judiciary, or the rights clientele? Politicians have a vested interest in depoliticizing im portant emotive questions. They inevi tably avoid taking stands by shifting responsibility to the judiciary for a question labeled Constitutional. The assets of incumbency can mean a life time sinecure for a congressman if he provides the usual constituency ser vices and remains noncontroversial. By removing emotive (e.g., busing, affirmative action, abortion) questions from the political realm and tolerating judicial legislation, he protects his flank. The judicial outcome is of only secondary concern to the careerist. Congressional efforts to thwart judicial usurpation are cosmetic ceremonies for the benefit of the uninitiated.

The ideologues—especially visible during the late 1960’s and early 1970’s—like to compare the United States with some norm of perfection. As a consequence, they are perpetually dis gruntled. Intoxicated with the need to “question authority” and to promote quick change, they have little loyalty to history, tradition, public opinion, or the requisites of order. They turn to the judiciary to legislate their latest fad. The post-World War II judiciary has been vital to the rights strategy. The nation waits breathlessly for the Supreme Court to make decisions that should have been made by the elected officials. The judiciary is far from ob jective in its legislative ventures. It over represents a certain milieu, certain law schools, certain pressure groups, and certain lines of argument.

Ambitious bureaucrats also play their parts in the rights drama. A bureaucrat on the make can invent a new “right” to attract attention and facilitate a promotion. Or he can apply the latest social science scheme to the political arena. New rights also en courage governmental expansion. The rights must be explained, clarified, and implemented. Violators must be apprehended and punished. A new empire has evolved.

The irony of the rights explosion is that the purported beneficiaries ultimately gain so little. A new right is proposed, and its supporters unambig uously promise some outcome. As the right comes to fruition, a structure develops around it involving jobs and routine. Seldom, if ever, are the poli cies examined to see if they fulfill the original objective. Busing and affirmative action were to be temporary reme dies! Who predicted that the novel privacy rights would lead to 15 million abortions? Thomas Sowell and Charles Murray have persuasively documented how little America’s Blacks have benefited from the numerous rights created in their behalf. The rights industry seems to develop a life and momentum of its own.

What might be done to counter the problems documented in these two books? Certainly more than a cosmetic response is required. Institutionally, the judiciary must be reintegrated as the lesser branch of government. Per haps a scrutiny of the roles of the judiciaries in the mature Western de mocracies would demonstrate the ab erration of American jurisprudence. Historically and comparatively, de mocracy has thrived without judicial activism.

More fundamentally, our need is a rediscovery of the concept of the com mon good/public interest as a norm for evaluating demands upon the system. Ideally the norm should encompass a transgenerational component—life viewed as a “chain of being” or as “a contract that links the living, the dead, and the yet-unborn.” Consequently, significant demands would be evaluated in terms of the general interest viewed with a concern for the claims of history and the claims of future generations. Accordingly, America needs a definition of corruption that extends beyond the illegal. The legal abuses documented by Lambro and the manufactured

rights examined by Morgan are corruptions and should be labeled as such. cc

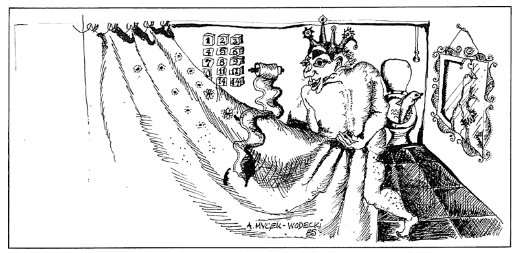

Image Credit: Wrongful ‘Rights’

Leave a Reply