“Quiet, Please,” by James O. Tate (The Music Column, August), was, like all his writing, excellent. I learned much, especially when he concentrates on providing historical and cultural knowledge. His formulation of how the internet can be of great help to those who already have an historical and literary formation, but overwhelming and even nefarious to those who do not, is unsurpassed. However, his statement that “there is no such thing as background music,” and that we should not use music for that purpose, has no historical basis. Music, and good music at that, has been used as background music for centuries, and such use has actually promoted the creation of great musical compositions.

For example, writes Steven Zohn in Music for a Mixed Taste (2008), “Around 1690 Johan Beer, Konzertmeister at Weinssenfels, observed that ‘just as French music is a special art, so it requires special admirers. Their suits sound well during meals. . . . And whoever is an admirer of them can presently derive great satisfaction from such compositions at many German courts.” Moreover, “By 1773 there was a long tradition of vocal and instrumental music associated with festive meals, especially those in courtly settings.” And Zohn provides this eyewitness account: “The large hall of the Niederbaumhaus was beautifully decorated, a dinner well-prepared, a stage erected and hung with tapestries for the vocal and instrumental musicians . . . ”

The Italians may have been pioneers of composing music as background for the aristocracy’s dinners: We have Carlo Grossi in 1681 in Venice composing Il divertimento de’ grandi: musiche da camera, ò per servizio di tavola. Much of Mozart’s music was likewise composed to be listened to while having dinner and engaging in conversation—as background music for the archbishop of Salzburg. Haydn’s music, too, was composed as background music. The tradition continues today in Germany, where one can enjoy a meal while talking to friends in Salzburg to the sound of Mozart’s music. (Was it Wagner who began the sacralization of musical listening?) And of course, music was played all the time at popular festivals in Italy.

So today, the lamentable thing is not that we listen to music while doing something else, like eating, or jogging, or writing an article for Chronicles, but that the music we listen to while doing such things is so bad. If the music is good, doing other things while listening to it is quite rewarding. If anything, confining good music to a big hall where we are all dressed up and sit quietly may contribute to turning off large numbers of people from the enjoyment of good music.

The problem is analogous to drama today, where usually mediocre or bad plays have actually been sacralized, and now we have to sit quietly in a hall watching some actors deliver de la prose. (My allusion is to Moliere’s Le bourgeois gentilhomme.) Whereas at the time of Lope de Vega or Shakespeare all the community, from the commoners to the aristocrats, attended the performance and ate (we know that vendors sold food inside the theater) and probably talked as well to one another or flirted while watching a play. The possibility that the superior quality of music up to the revolt of the masses (I am making reference to Ortega here) was the result of its being written for listeners with a superior taste and training (the aristocracy), or, in the case of plays, the result of their being written for a public with a superior capacity for appreciating well put together words (both an aristocracy brought up on the classics and a popular mass that listened every week at church to well written and delivered sermons composed by literate priests also educated in the classics, or at least written and delivered by pastors educated in the wonderful prose of the Scriptures), should be the subject of an article or a book.

—Darío Fernández Morera

Northwestern University

Professor Tate Replies:

I see the professor’s point, and he has much truth on his side. I can see that he reads Chronicles, and that he is not only a scholar but also a gentleman. I do appreciate those qualities, and I do remember that Maria Barbara, the princess of Portugal, as she became the queen of Spain, provided for her personal musician, Domenico Scarlatti, not only a house but an orchestra to play for his dinner. So yes, it was right for them, and if they did not know, then no one can. I also take the point that pomposity doesn’t serve music well, or much else either.

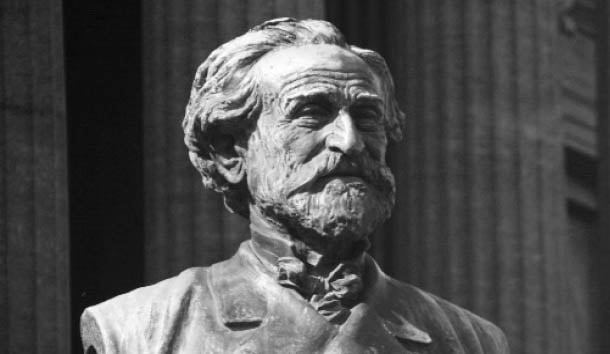

I do have a few other thoughts. One is that I centered my assertion on the postindustrial period, which offered a chance at the abatement of noise. Let me define my terms. When the aged Giuseppe Verdi was dying in a Milan hotel, the city laid straw on the streets to muffle the sounds of the horses’ hooves. In effect, the whole city went on a quiet campaign for the peace of one great man! I admit my model of deportment here is a bit extreme, but it is authentic. But let us change the image to the young Verdi. What did he hear in the village of Busetto when he was a boy? The clink of an anvil? A church bell? Horses? Anything else? And what did he not hear? He heard no noises that were amplified, little if any street noise, nothing electric. He heard the town band and the music of the church choir. No ten-year-old today would ever be so lucky, or he would condemn the situation if it were so.

I believe that one kind of order relates to another—conversely, disorders are related as well. Music is a form of order, and I seem to recall that an ancient philosopher declared that the wrong music was harmful to the polity or even the state. Discursive disorder is a threat to our lives, not merely our smugness. Disorder from the masses is nothing new, and neither is disorder from the leadership. Today we have both, as well as disorder from the center in the form of the collapse of education. If we can’t even get music right, then what can we do? Manufactured and amplified noises 24/7 do not quite compare to acoustic music at the polite dinner hour more than two centuries ago.

In this regard and in others, I thank the professor for his attention and informed reflections.

Leave a Reply