Few people have been so hated that their enemies have disrupted their funeral processions in an attempt to throw their coffins into a river, but that is precisely what happened to Pope Pius IX on the night of July 12, 1881.

Amid the heated debate surrounding Pio Nono’s beatification this past September 3, a few articles mentioned this episode. But with the notable exception of Inside the Vatican (March 2000), no one indicated that this attempt was not an isolated attack during an otherwise peaceful two-hour march from the Vatican, where Pius IX had been temporarily buried after his death, to the Basilica of San Lorenzo Outside the Walls, which the Pope had chosen as his final burial place. Indeed, it was only one of the highlights of an incredibly stormy procession, which turned into a real road to Calvary for the immense crowd of Roman faithful determined to pay a final tribute to their beloved Pope. The funeral cortege had to make its way through horrible blasphemies, insults, curses, obscene songs, stone-throwing, and clubbings. Many mourners were seriously injured.

The attacks were carried out by a few hundred freemasons and liberals with the virtual connivance of the police force, who showed no respect whatsoever for the Catholic faithful and their sentiments. Rome had been “liberated” from the Pope’s temporal authority 11 years earlier, and the police were serving a prime minister, Agostino Depretis, who was known for his hostility toward Catholics.

Almost 120 years later, the harassment continues. The spiritual heirs of the anti-Christian hecklers may resort to more sophisticated tools, including the media, but their intention is the same; to disparage die figure who, more forcefully than anyone else, denounced their errors, which are the root cause of die profound crisis in contemporary society. Pius IX repeatedly and forcefully condemned socialism and communism beginning in 1846, two years before Marx and Engels published the Communist Manifesto. Had his appeals been heeded, mankind would have been spared the mass murder of tens of millions of people during the 20th century.

Msgr. Carlo Liberati, an official at the Vatican’s Congregation for the Causes of Saints, argued in Corriere della Sera (July 13) that the major American media are in the forefront of this smear campaign, particularly the New York Times and the Washington Post. While these newspapers have alleged that Pius IX was antisemitic, Msgr. Liberati claims that the contrary is true: Pius IX promoted true freedom for Rome’s Jews. The gates of Rome’s Jewish ghetto were pulled down under his instructions, and Pius deployed patrols in the area to protect the Jews from those in the Roman populace who were upset by their emancipation.

The American media made much of the case of Edgardo Levi-Mortara, a Jew from Bologna who, when he was 17 months old, was secretly baptized by his Catholic nanny because he seemed about to die. Mortara survived, but his parents, when informed of his baptism, refused to bring him up in the Catholic faith. In accordance with canon law, on June 24, 1858, the child (then six years old) was brought to Rome, where he was educated under the personal protection of the Pope. Eight days later, his parents arrived in Rome, where they stayed for a month and pled for his return. Although he met with his family on a daily basis, Mortara never showed the slightest desire to rejoin them, as he himself later attested. In his teens, Mortara returned for a month to his parents, but he ultimately decided to settle in Rome and become a Catholic priest. He was one of the first witnesses to give testimony in favor of Pius IX’s beatification.

When Piedmontese troops entered Rome in 1870, they hurried to they convent where they thought the 19-year-old Mortara was being held captive. To their surprise, he not only categorically refused to be “liberated” but made it clear that he had decided to take religious vows and to join the Lateran Canon Regulars. While churches and monasteries in Rome were being turned into stables, prisons, and army barracks by the very “liberals” who had come to “free” and “protect” Edgardo Mortara, he wanted to become a priest. In the end, he chose to expatriate rather than to serve the Pope’s enemies. He became a well-known itinerant preacher, able to deliver sermons in nine different languages.

Why “was such a scandal raised for one child,” Msgr. Liberati asked the Washington Post, “when thousands of Polish children were deported to Russia [in the same period] and forced to become Orthodox, and nobody protested?” Forced conversions arc still die order of the day in Muslim-dominated areas; unlike Christians who are unwillingly inducted into Islam, however, Edgardo Mortara could have returned to his family’s faith, had he wanted to, without fearing for his life.

Canon law has always condemned forced conversion and baptism against the will of a child’s parents. Popes imprisoned Christians who violated this canon; and in the Papal States, a fine of 1,000 gold ducats (a huge sum) was imposed on anyone found by the courts to have done so. Jewish families in the Papal States were not allowed to employ Christian servants, not on antisemitic grounds but precisely to avoid the types of problems raised by the Mortara case. For Pius IX to endure what he did for the sake of one child, knowing the international storm he would unleash, he must have had a compelling reason. To put it bluntly, he was either insane or a saint.

In his recent book Pio IX (Piemme), Prof. Roberto de Mattei (who holds the chair of modern history at the University of Cassino and is the president of Centro Culturale Lepanto, a Rome-based organization of lay Catholics) finally sets the record straight. Pius’s beatification, de Mattei believes, presents a perfect opportunity to revisit the history of his pontificate. Moreover, his beatification vindicates his memory, prosing him right and his detractors wrong.

Pius IX decried the evils of his time as the seeds that would eventually grow into what Pope John Paul II calls the “culture of death.” Divorce, abortion, and euthanasia are the visible results of the sweeping de-Christianization that Pius IX steadfastly fought throughout his pontificate. This same secularization gave rise to the totalitarianisms of the 20th century, with their genocides, gulags, and concentration camps. While Pius IX may have lost the initial battle, his vision may, in the long run, help win the war by providing guidance for a future restoration of the principles and institutions of Christian civilization.

De Mattei’s biography of Pius IX, combining the rigorous approach of the professional historian with clear and forceful language, is suitable both for the expert and the layman. It also helps to correct the impression left by Fr. Giacomo Martina, a Jesuit who composed a three-volume biography of Pius IX, only to end up opposing Iris beatification.

While the tribulations that characterized Pio Nono’s pontificate are well known, the theological and moral implications of his teachings are not. As de Mattei points out in his introduction, Pius IX’s vision of history and society was profoundly counterrevolutionary. He viewed the Renaissance, Protestantism, the French Revolution, and the Risorgimento (the Masonic-inspired movement that led to the unification of Italy) as different stages of a century-long revolution that was attempting to replace Christian civilization with an anarchical and egalitarian universal republic.

Inspired by St. Augustine, Pius IX viewed contemporary events through a “theology of history” that saw human life in terms of two cities destined to fight each other until the end of time: the “Civitas Dei,” namely, the Catholic Church; and the “Civitas Diaholi,” represented in his day by the European and Italian revolutionaries. But Pius IX did not limit his vision to opposing contemporary evils: he presented the papacy as the only force able to defeat the forces of anti-Christian revolution and pave the way for the revival of an authentic Christian civilization.

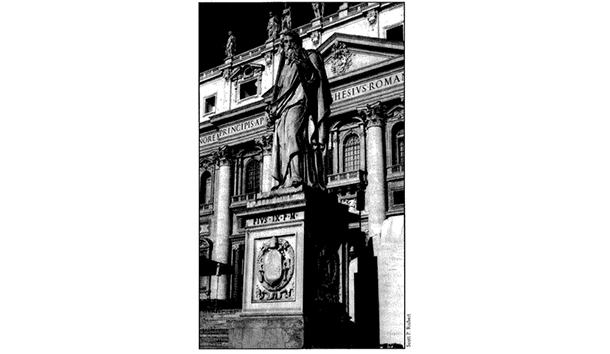

Pius’s tenure as Pope coincided with the height of the clash between the Catholic Church and the modern civilization that arose during the French Revolution. The strife erupted in unprecedented virulence during the first three years of his pontificate, forcing him to choose between the principles he incarnated and the new ideas with which he initially sympathized. In fact, he started his pontificate by granting amnesty to political prisoners and promoting reforms, but he soon backtracked when he realized that his moves, far from appeasing the radical nationalists, actually helped them to pursue an increasingly bold agenda, which included insurrections and assassinations. A statue of Blessed Pope Pius IX in front of St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City. Following the revolutionary upheavals of 1848, Pius IX realized that no reconciliation was possible between the divine Church, founded In Jesus Christ and entrusted with the mission to announce His Gospel, and those revolutionary forces hell-bent on undermining this mission under the pretext of the Risorgimento, which was tantamount to an anti-Gospel based on a denial of natural and Christian law. Once Pius became fully aware of what was at stake, he devoted himself to opposing and reversing the resolution with the full might of his pontificate.

In the leftist newspaper Il Manifesto (June 30), Father Martina, the Jesuit biographer of Pius IX, claimed that his opposition to Pio Nono’s beatification was motivated by a belief that the Pope would not enjoy a sufficient degree of popular devotion. Yet a thousand faithful from around the world flocked to the Basilica of San Lorenzo in Lucina on September 2, the eve of the beatification ceremony at St. Peter’s Basilica, for a solemn pontifical Mass m honor of Pius IX, which featured plainchant sung by the Cappella Musicale Choir of St. Peter’s. After the Mass, in a nearby square, a military band played national and popular anthems of Italy’s states from before the Risorgimento. By comparison, an anti-clericalist demonstration, protesting the beatification of Pius IX and what the organizers fear may be the beginning of a Catholic revival, did not draw more than 50 people. A similar demonstration on September 20 drew a larger crowd: About 100 people rallied to celebrate the 130th anniversary of the breach of Porta Pia, the hole in the city’s walls through which the Piedmontese troops stormed the city, completing Italy’s unification in 1870.

The attacks on historic Catholic leaders, as Roberto de Mattei notes, are ultimately aimed at the Church Herself. As Alfons Cardinal Stickler wrote in the preface to another of de Mattei’s books, The Crusader of the 20th Century (a biography of Tradition, Family, and Property founder Plinio Correa de Oliveira), “[T]he true object of these accusations and falsehoods is the Church and . . . they are made to deny the Church’s role as the ‘teacher of truth,’ recently affirmed by the Holy Father John Paul II in Veritatis Splendor.”

The same John Paul II, through his secretary of state, Angelo Cardinal Sodano, publicly commended Professor de Mattei’s biography of Pius IX with the following message, which was read during the official presentation of the book in early September:

On the occasion of the presentation of the volume Pio IX by Professor Roberto de Mattei, the Holy Father extends his goodwill greetings with the hope that the historical investigation will be instrumental in promoting a better knowledge of the life and deeds of his illustrious predecessor. Wishing the cultural event a fruitful outcome, he imparts the author of the book, the speakers, and the attendees his apostolic blessing.

A conference held in conjunction with the official presentation debunked other myths surrounding Pius IX. Pio Nono did not reject modernization per se, but modernity as a process of secularization, antithetical to tradition. The ideological tenets of the Risorgimento, he believed, would destroy traditional society and Christianity. While Pius IX is often described as “anti-Italian,” he was not against Italian unification in itself. He did, however, oppose the Risorgimento once he realized that the movement was becoming increasingly anti-Christian.

Many historians view Pius IX as a saint in his personal life, while claiming that he was politically naive. But de Mattei, who does not conceal his sympathy and admiration for Pius IX, argues that the Pope cannot be deconstructed: His religious approach cannot be separated from his policies; his private life is inextricably bound up with his public life. By splitting his personality, the detractors of Pius IX (as well as some of his defenders) attempt to revive the tired proposition of liberalism that separates the personal dimensions of human life from the public dimension, man from society, and morals from politics. The most serious political evils, however, have their origin in the pretense that politics is independent of morals. Pius IX held the opposite view, which is both classical and Christian: Politics is a category of morality, to which it must be strictly subordinated if it is to be ordered to the common good.

The proper relationship between society and the individual. Church and state, and politics and morality was the central concern of Pio Nono’s pontificate. The roots of this problem date as far back as Renaissance Italy, when Machiavelli emancipated politics from morality, turning it into a mere tool in the pursuit of power. From that time on, the “raison d’état” has been the supreme yardstick for governmental action. Count Benso of Cavour, who believed that any means, however immoral, were justified if they served the cause of national unification, most fully incarnated this Machiavellian understanding of politics. As such, the Piedmontese count as Marxist theorist Antonio Gramsci noted in Note sul Machiavelli, is not only the heir of Machiavelli but the real “Italian Jacobin,” the authentic forerunner of those 20th-century “professional revolutionaries” who have subordinated morality to politics, following the well known formula of Lenin. Since the time of the Risorgimento, Italian culture, in the name of personal and national autonomy from morals, has aggressively pursued secularization, which Gramsci described as the “complete de-christianization of all life and customary relationships” and the “absolute mundanization and earthly connotation of thought, an absolute humanism of history.”

To combat the cultural vision that came to dominate Italy after its unification, Pius IX presented a “religious option,” which constitutes the interpretative key of his pontificate. He strenuously opposed the secularization of society, which denied any action of God in the affairs of mankind. Instead, he aggressively championed a political philosophy that—following Aquinas, Dante, and Vico—regarded polities and morality, as well as the temporal and spiritual orders, as distinct but not separate realities, and he sought a balance between the two spheres. More than the loss of the Papal States, Pius wrote to King Pedros V of Portugal on October 22, 1862, “What afflicts my heart is this turnaround of principles, this planned loss of moral sense and rightful guidance.” He viewed temporal power as a means ordered to the supreme, supernatural ends of the Church, which is the true master of faith and morals in the civil and social, as well as religious, spheres.

Despite his beatification, Pius IX remains largely unappreciated. His every public act—religious, political, and social—stemmed from his profound interior life and can only be understood in the context of his Christian anthropology and theology of history. Pius IX viewed the divine will as the supreme rule of human behavior, and he was adamantly convinced that God guides not only the life of individuals, but that of mankind, as if it were a single entity. “I do not want to move away a single inch from divine will,” he used to say. His efforts to comply with that will in all his actions were recognized as heroic by the Church and supernaturally confirmed by the miracle required for his beatification.

The solemn beatification ceremony on September 3 celebrated not only the doctrinal highlights of Pio Nono’s pontificate, but all of his private and public deeds: the political, social, and administrative reforms that he instituted; his Syllabus of Modern Errors; the extraordinary missionary zeal that he infused into the Church; and the cultural and moral revival of Catholicism in the 19th century. The man, the priest, the bishop, the sovereign, the Pope—Pius IX was beatified in his entirety.

Leave a Reply