By undermining the Western canon in the 1990s, leftist academics paved the way for today’s ‘woke’ hurricane.

When I finished graduate school at UCLA in 1988, I believed that English sat at the top of the academic heap. The department claimed nearly 1,700 majors; the nonmajor survey courses I taught during the year after I filed my thesis had more than 400 students each; and professors and administrators across the quad were eager to know what this thing called “deconstruction” was. The department required of every major a yearlong survey course, from Beowulf to W. H. Auden, with a syllabus that proclaimed, “This is English, the full sweep!” Earlier, in 11th-grade English, I got the same thing for American literature, a grand patrimony from Hawthorne to Hemingway, implying the country’s own grandness. English was where you found the meaning of the past. Without a flagship English department, a university could not be a tier-one institution.

It wasn’t only a campus thing. One year before, a book by a renowned literary theorist at University of Virginia spent six months on The New York Times’ best-seller list—not Allan Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind but E. D. Hirsch’s Cultural Literacy, wherein the famous list of terms in the appendix was heavy on literary subjects. In 1986, The New York Times Magazine profiled Yale English faculty and their guru, Jacques Derrida, giving them a certain amount of notoriety and celebrity. If you turned on the television, you might see literary scholars Stanley Fish and Catharine Stimpson battling William F. Buckley Jr. and Dinesh D’Souza over political correctness, as happened in a forum moderated by Michael Kinsley in August 1991. And in 1984, William Bennett’s National Endowment for the Humanities published To Reclaim a Legacy: A Report on the Humanities in Higher Education, which regretted the spread of ideology and theory in literary study—but it only proved how important English professors were.

How quaint it appears at this late date: conservatives and liberals arguing over literary tradition, debating a Shakespeare requirement and asking whether Zora Neale Hurston belongs next to Faulkner. When Jesse Jackson spoke in 1987 at Stanford in a warm-up for another presidential run (his 1984 Rainbow Coalition still had momentum then), students marched away decrying a general education requirement at the school, a mostly literary course: “Hey hey, ho ho, Western Culture’s got to go!”

We English majors loved hearing of these developments. I was an obedient liberal at the time who nonetheless favored Great Books and Western Civ. I didn’t want to see those courses go down, but the bare fact of public attention to literary studies was a reward in itself. Those of us just entering the field could easily believe that we worked at the center of American controversy. It was exhilarating. Even if we didn’t much care about politics, our archival digging in the library and the tortuous critical readings we did of Leaves of Grass and Macbeth would have an impact. People cared about our subject matter.

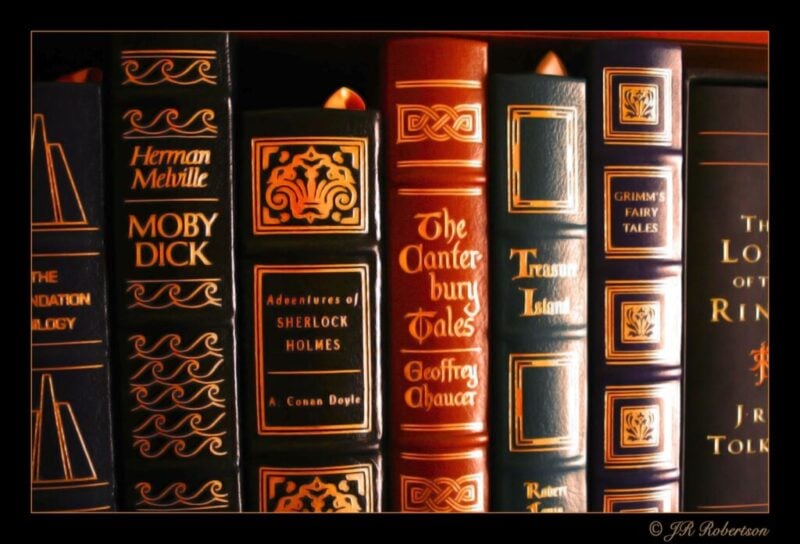

(photo by Randy Robertson /

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

It didn’t last long, of course, only a few years, sometimes going by the name “Canon Wars” to depict the controversy over who should and who should not be included in the standard Western literary canon. It was all over and done by the mid-’90s, when the Culture Wars moved on to gays-in-the-military and the Contract with America, followed by Bill and Monica. English, too, began to slide. One year after the Jackson event, the Stanford faculty scrapped the Western Culture requirement.

Literature departments suffered a loss of market share; the number of bachelor’s degrees in English hovered around 50,000 at the same time that the graduating population was booming, climbing from 1.16 million in 1995-96 to 2.01 million in 2018-19. In the last few years, in fact, English has fallen to around 40,000 degrees per year, its share of majors dropping from 4.3 percent in 1995-96 to 3.7 percent in 2004 to a feeble 1.9 percent in 2018-19. Literature itself became less seminal within the departments. Professors preferred to speak of cultural studies, queer theory, and postcolonialism, not of Hamlet or Emma Bovary.

By 1998, when I’d made it to full professor at Emory University, the conservative defense of Western civilization and the great American novel was nonexistent in the faculty lounge. Just a year before, a book by UC Santa Cruz Professor John Ellis bore a simple and summary title: Literature Lost: Social Agendas and the Corruption of the Humanities.

The reigning theories of the ’90s abandoned literary language for the racy topics of sexuality, politics, and race. Everyone was a diversifier, adding gender theory, media studies, and other nontraditional subfields to their professional profiles, or at least declaring themselves as such at critical moments—for instance, during a department vote over changing course requirements for the major. While conservative critics Roger Kimball, D’Souza, Bennett, et al. wrote books that each outsold any 100 academic tomes put together, the professors went on steadily, unblinkingly with their dismantling project. The very idea of a core Western or American literary tradition was off the table.

For many years afterwards—having worked off-campus at the National Endowment for the Arts and, later, at First Things magazine (while still teaching at Emory)—I believed that the decline of literary studies was an all-academic affair. The language of theory was too recondite for anyone but insiders, and too many academics came off as goofs and misfits when out of their professional zones. Who else but eccentric PhDs would listen to Judith Butler go on about gender and sex in her turgid prose? Why would anyone take seriously an English professor declaiming the “truths” of imperialism and Cold War geopolitics? What do English professors know about such matters?

Others thought the same thing. When I started to frequent conservative circles in the early 2000s, I often heard it said that there was a silver lining to the politicization of the humanities. Thank goodness that the Marxists and multiculturalists had camped out in literature departments, the argument ran. At least nobody will pay attention to them. The enrollment declines were understood as healthy, a sign that sensible undergrads rightly avoided the tenured radicals. Settled in ivory tower units slipping in popularity, the professors would do less damage. Their blather about capitalism and patriarchy and whiteness would have a smaller captive audience, and people who really knew about such things (economists, social scientists, and biologists) would recognize the blather at first sight.

We got it wrong; I realize that now. Yes, literature professors left literature and dove into social/political matters they weren’t trained to understand, but to feign expertise in race and sex and politics was not the point. The positive labor of social-political analysis wasn’t the real goal, nor was keeping the English major strong. The real goal had already been accomplished, and right in front of us: the demolition of literary tradition, of a Western literary canon and an American literary canon. Still, the politically moderate, open-minded liberals on the faculty (I was one of them) didn’t want to admit it. Our more aggressive colleagues pushing “diversity” just wanted a more diverse syllabus, so they said, and we believed them, because disbelieving them would mean ascribing to them lesser motives, destructive ones, and that wouldn’t be collegial. It wouldn’t be liberal.

But once the multiculturalists got rid of the old canon, their promise of a richer, fuller curriculum of multiple cultures never materialized. After Stanford dropped the Western Culture course, it created a diversity replacement for it, expecting all the professors who denounced the old to teach the new. Well, they didn’t show up. Stanford had a hard time getting professors into those classrooms. The outcome proves the point. They didn’t want a new and improved humanities curriculum, adding Toni Morrison to Shakespeare, adding wives and mothers to kings and generals in history courses. No, the revolutionaries just wanted to take out the Western/American heritage. They didn’t aim to share space with traditionalists, no deference to “Can we all get along?” The tradition had to go, period. “Diversity” was a dodge, a tactic, a temporary step in the discreditation of the old.

It worked. When we look at English departments today, we see no organized, cumulative sequence of study that guarantees students will learn strands of women’s literature, African-American literature, and Native-American myths, along with classic American literature. Instead, we have a mishmash of courses straying into identity politics, media, and various agenda-driven critical theories, with some novels and poems serving as pretexts. No consistent threads, no coherence, save for the firm objection to anything that smacks of a restoration of the old.

To cast America First as an Alt-Right insurgence, first one had to dispel the other America, as preserved in Emerson, Hawthorne, Melville, Thoreau, Douglass, Whitman, Dickinson, Twain, Wharton, and so on. The old syllabus showed America had a lineage of American-ness, an exceptional descent, our own to identify and absorb.

This is one of the major successes of the left. Take a look at the reaction to a couple of the greatest speeches given by a U.S. politician in living memory. At Warsaw on Jul. 6, 2017, President Trump envisioned the Western past in ways that hearkened right back to the Canon Wars of the ’80s. He cited Copernicus, Chopin, Saint John Paul II, and Polish heroes of science, music, and religion. He spoke of “national characters” and “the will to defend our civilization” and the desire for God. “We write symphonies,” he said. “We celebrate our ancient heroes, embrace our timeless traditions and customs.” By “our,” he meant Europe and America, the West, and he declared at the end, “And our civilization will triumph.”

Three years later, on July 4th, he delivered a complementary speech at Mt. Rushmore, where he announced, “Seventeen seventy-six represented the culmination of thousands of years of Western civilization.” He proceeded to extol the four faces, Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, and Teddy Roosevelt, who “exemplified the unbridled confidence of our national identity and culture.” Nods to Buffalo Bill, Wild Bill Hickok, and the Wright Brothers followed, then to Jesse Owens and George Patton, Walt Whitman and Mark Twain, Irving Berlin and Ella Fitzgerald, Bob Hope and Elvis Presley, among others—a canon of American expression and action, a fabulous lineage of American greatness.

And how did the media respond to these commemorations? An article in Foreign Policy bore the title, “Trump’s Mt. Rushmore Speech Is the Closest He’s Come to Fascism.” The New York Times called it “a divisive culture war message,” a “dark and divisive speech,” while the Associated Press accused him of “pushing racial division” and Vox called it “fearmongering.”

Reaction to the Warsaw speech had been the same. Peter Beinart in The Atlantic labelled it “racial and religious paranoia” while The Guardian cast it as “dark nativism,” Vox as an “alt-right manifesto,” and Slate as “white nationalist rhetoric.” The Washington Post called it a “white nationalist dog-whistle,” and the The Village Voice said it sounded like something you’d hear in a “Thirties Berlin rathskeller.”

To be sure, both speeches had their defenders, at National Review and elsewhere, though what could one say to the hysterical characterization of Trump’s words as the onset of fascism? I remember watching CNN right after the Warsaw event and hearing a guest casually refer to the speech as a flat case of white supremacy, as if it were an obvious fact, indisputable. In her world, this was received wisdom: Western Civ equals white supremacy, clearly and unexceptionally.

The blithe utterance of such a noxious charge on a network broadcasting in airports across the country goes to show that the Canon Wars of the late 1980s were not merely an academic squabble. In those former times, the only place you would hear such a radical equation was in a few hard left activist organizations or in obscure corners of the universities, but certainly not in mainstream news outlets.

Now, what was once a quirky and bilious academic indictment is conventional liberal opinion. In 1984, the phrase “Make America Great Again” wouldn’t have offended anybody in the public arena. It would only echo another campaign slogan from that time period: “Morning in America.” In 2016, however, MAGA evoked in academics, intellectuals, and journalists images of Nuremberg—or at least they pretended it did—and the pretense brought them attention and advancement.

It wouldn’t have worked if the universities hadn’t paved the way for it. We must recognize the full consequence of the fall of an American literary canon. To cast America First as an Alt-Right insurgence, first one had to dispel the other America, as preserved in Emerson, Hawthorne, Melville, Thoreau, Douglass, Whitman, Dickinson, Twain, Wharton, and so on. The old syllabus showed America had a lineage of American-ness, an exceptional descent, our own to identify and absorb. And by that acknowledgement, the nation was unified, its past stable and coherent—and good. The literary canon authorized it. However much they dreaded 11th-grade English, youths got a sense of their country through Hester Prynne and Huck Finn and Gatsby, Rip van Winkle and the Joads. These literary characters formed what every nation needs: a body of works with a national meaning. Take that away, keep the patrimony from the rising generation, and the nation forms less clearly in their hearts and minds. Young Americans are consequently less inclined to defend their country.

This was a terrible loss for conservatism and a key victory for the left. The reaction to Donald Trump indicates how important this academic skirmish of prior decades was to the other side. While the right focused on law and economics, the left in its strategic vision went after the cultural foundations, playing a long game that has resulted in the Woke hurricane now sweeping through institutions from Berkeley to Wall Street, the NFL and the Navy and the Salvation Army. Yes, there is a line to draw from Herman Melville and Robert Frost to strong borders and the First Amendment. Citizens who have no knowledge of the greatest users of the American language don’t have a deep conception of America itself. One can’t be loyal to a formless past.

Leave a Reply