A French woman who met the American poet Allen Tate (1899-1979) in the 1930s remarked, “Monsieur Tate is so conservative that he’s almost radical.”

Etymologically, “radical” fits Tate well; his conservatism entailed returning, in the face of destructive social practices, to fundamental truths and the established customs embodying them, many immemorial. He espoused the primacy of families, the value of the individual person (in the Christian sense), “organic” communities, and attachment to the soil. He gave importance to local and tribal history and earlier ancestral connections—that is, ethnicity. Likewise, he valued classical literary traditions and the English language. He could have adopted for himself the watchword of the conservative French nationalist Maurice Barrès, who proclaimed his loyalty to the earth and the dead: “La terre et les morts.”

Above all, Tate was a Southerner. The context for his conservative positions was that of the defeated, often despised, but honorable South. His perspective was not, however, limited to his section; it reflected his grasp of the spiritual crisis of modern man, exacerbated in the Great War and the following decades.

It may seem strange that Tate was for years a disciple of high modernism, a literary movement that was radical in the more common meaning. While it had pre-World War I roots, in its full-blown form it was a product of the watershed of 1914-1918 and the ensuing moral crisis, identified by countless observers, including D. H. Lawrence and Paul Valéry, who remarked, “We civilizations know now that we are mortal.” Like William Faulkner, among the few Southerners then attracted to the new vein, whether in poetry or prose, Tate became acquainted with modernism and its characteristic irony partly through the early and mid-career writing of T. S. Eliot, whose example was instructive.

Discarding Matthew Arnold’s “sweetness and light” and the Victorian poetics still current in America in the early decades of the 20th century (Willa Cather’s April Twilights, for instance), Tate learned to employ irony as a corrective poetic mode. This mastery conferred on him an authority that even his cultural detractors, such as H. L. Mencken, could not gainsay. Tate read deeply in Eliot’s essay collection The Sacred Wood (1920), and, following that example and his own Southern leanings, devised a robust conservatism that included conversion to the Roman Catholic Church in 1950. (Tate called Southern Protestantism “a non-agrarian and trading religion.”)

Thus, while Tate’s poetics were modern, his poems reflected his cultural positions, including the famous “Ode to the Confederate Dead”; its larger theme was, he said, “the cutoff- ness of the modern ‘intellectual man’ from the world.” In one passage, he turns the reader, who no longer has access to a tradition of public recognition of the South’s heroic past, “to stone” at the sight of a Confederate graveyard:

On the slabs, a wing chipped here, an arm there:

The brute curiosity of an angel’s stare

Turns you, like them, to stone,

Transforms the heaving air

Till plunged to a heavier world below

You shift your sea-space blindly

Heaving, turning like the blind crab.

In addition to poems, Tate published criticism, biographies of Stonewall Jackson and Jefferson Davis, fiction, and numerous essays. He became, essentially, a public intellectual representing conservative thought. Paul V. Murphy, a historian of the Southern Agrarians, called Tate “perhaps the most influential southern intellectual in the mid-twentieth century.”

Born in Kentucky of an ill-matched couple, Tate was, it seems, deliberately misled by his mother into believing that his birthplace was Virginia, her own ancestral home, with its uncontested prestige, if not superiority, among the Southern states and its peculiar Southern experiences and loyalties. It took him years to throw off her misdirected influence. His childhood and adolescence were marked by nasty parental quarrels, frequent moves, and irregular schooling. Despite the disruptions and his often unpromising academic performance, he was admitted to Vanderbilt University. There, he was soon recognized as highly talented by those who formed in the 1920s the extraordinary group called the Fugitives, part of the Southern literary renaissance.

Tate’s career cannot be separated from that milieu. With their little magazine of the same name, the Fugitives changed the literary landscape in the South, boldly heading off toward a revived, vigorous Southern poetry based on their sense of place. They were spurred, no doubt, by Mencken’s scorn for the South, “the Sahara of the Bozart.” Readers elsewhere—New York, Boston, New Orleans, and eventually London—recognized the importance of The Fugitive. Published from 1922 through 1925, it initiated an unprecedented and unabashedly Southern poetic renewal. The program was not fixed from the outset; it emerged from poetic momentum, abundant talent, and the connoisseurship of a few prosperous supporters. Excellence, not sectional loyalty, was the standard. But the major contributors were Southerners and devotedly so.

Nonetheless, the young Tate sought to establish his literary fortune in New York in the mid-to-late 1920s, a choice which the other Fugitives shunned. His efforts bore fruit— he found publishers and made friends among high-placed literati—but it was not the right milieu for him in the long run. In fact, he suffered there. His perspectives on the South afforded by those years and subsequent stays in England (where his first poetry collection earned praise from Robert Graves) and on the Continent were, however, useful: “I’m one of those people,” he stated, “who must stand a long way off before I can see what is under my nose.”

Among others whose reputation is bound up with The Fugitive and the 1930 symposium I’ll Take My Stand: The South and the Agrarian Tradition, or both, were Donald Davidson, Andrew Lytle, John Crowe Ransom, and Robert Penn Warren. The last, with his three Pulitzers and other high honors, surpasses all his fellows in fame. Yet Tate is perhaps a better standard-bearer. Along with his similarly high poetic achievement and countless honors, he stands out by his unwavering Southern loyalties and well-reasoned convictions.

above: book cover for I’ll Take My Stand: The South and the Agrarian Tradition by 12 southern authors, first published in 1930 (Harper Torchbooks)

Tate’s novel, The Fathers, which hearkens back to the 1860s and his own family, shows his determination to search the past, not to discard it, but through it to understand the present. Warren, having defended in 1930 the “separate but equal” racial policy codified in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), later moved leftward, at least on race relations, becoming a vocal supporter of the civil rights movement.

above: book cover for The Fathers by Allen Tate, first published in 1938 (Swallow Press)

I’ll Take My Stand, the Southern manifesto of “radical conservatism,” in Murphy’s term, was founded on what Tate called “a belief in the dignity of human nature” and a proper understanding of this nature. Commitment to states’ rights was a given. The undertaking was both diagnostic and, to use the contributors’ own word, “prophetic.”

The Southerner, wrote Ransom in the manifesto, “identifies himself with a spot of ground, and this ground carries a good deal of meaning; it defines itself for him as nature.”

The manifesto confronted the racial question directly, by arguing various viewpoints. Tate, then and later, favored decent treatment for blacks, supporting especially their right to vote, which, when fully exercised, would give them a voice in policy. Looking to the Southern past, he saw two evils in bondage—the humiliation it imposed and the inability of talented slaves to rise above their condition. But he believed, like John C. Calhoun, that the institution had been “a necessary element in a stable society.”

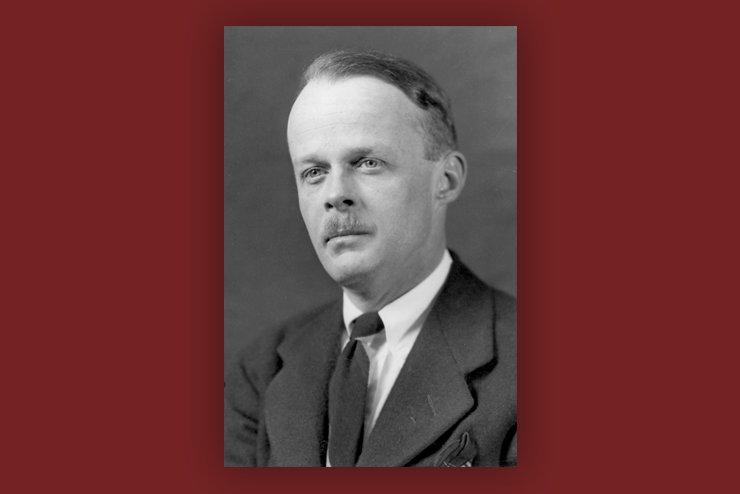

above: Allen Tate c. 1960 by Peter Marcus (University of Minnesota Libraries, University Archives)

Tellingly, Tate saw that the South was not alone in its sectionalist tendencies. In 1936 he remarked to Lytle (the most soil-bound of the Fugitive circle) that American Westerners and Southerners were spiritual mates. Westerners were “fine folks…real agrarianism, no factories, no rush. Dislike of East, great interest in South.”

Although the Agrarians were called reactionary and “fashioners of utopias” (Mencken’s phrase), Tate’s conservatism was proactive, and not simply the maintenance of curmudgeonly old ways or nostalgia for an impossible pastoralism. He argued that “reaction is the most radical of programs; it aims at cutting away the overgrowth and getting back to the roots.” He described his political philosophy as “Jefferson modified by Calhoun.”

Tate began, thus, with denunciations: of industrial overdevelopment, urbanism, rootlessness, godlessness, and the idol of mindless progress. These features, reflecting Yankee greed, had created the New South, heralded as both a source of wealth and partial undoing of past errors. Ultimately, he blamed “the defeat of independent agrarian communities in the South” on the War Between the States. Finance capitalism and industrialism would, Tate foresaw, continue to expand, along with a powerful regulatory welfare state.

The roots to which society should return were not just practical; they were broadly cultural, religious, and even literary. By what means could the return be effected? What expectation was there of curtailing federalism, progressivism, the power of universities (which Tate attacked explicitly)?

Tate had no use for Bolshevism, which he called “law and order carried to tyranny.” What he could embrace, along with his fellow contributors to I’ll Take My Stand, was a gradual reduction in the scale of industrial and business enterprises, a recognition of traditional beliefs, local ownership, and small-scale farms and commerce, all based on regional practices. He tried to disseminate this platform— a fundamentally romantic one—among Southern farmers. But it could not pass as a white paper for the redesign of land management and economic reorganization in any one state, still less for the nation—even had the forces of ownership and capital agreed to any part of it.

The Southern “conservative revolution” would be, finally, a moral one. Tate wanted to emphasize the whole man, not the fractured, serf-like creature of impersonal capitalism, estranged from even the material products of investment. Family, heritage, and religion would all contribute to nurturing the human person. Unfortunately, the vision for which the Agrarians argued became anachronistic because of changes wrought during World War II and after, which made minimizing industry unthinkable.

Shelley asserted that poets were “the unacknowledged legislators of the world.” In Alfred de Vigny’s play Chatterton (1835), an industrial tycoon asks what purpose poets can serve in a practical, commercial society. The answer is that the “poet reads in the stars.” Tate’s vocation was to express a vision of the good, true, beautiful—and durable—and to do so tirelessly.

Image Credit:

above: undated portrait of Allen Tate by Gonville de Ovies (Wikimedia Commons/Library of Congress)

Leave a Reply