Fashions do not feed us, they only ensnare us. They do not satisfy us, they only contribute to our ongoing dissatisfaction with the fleetingness of everything. But they always seem more appealing and urgent than what really matters and what will remain after the fashions have fled.

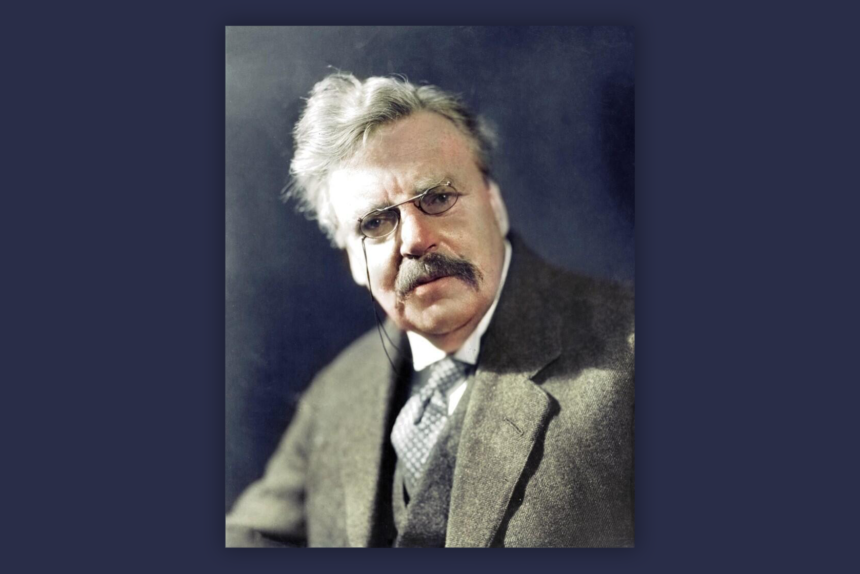

English writer Gilbert Keith Chesterton (1874-1936) was once very popular, but he was never fashionable. He made a career out of counteracting the latest, speaking out against the trendiest, counseling against the reformers who never knew what the form was, and defending those who clung in the corners. He was only interested in what was true, which seldom was the new. “Fallacies do not cease to be fallacies even if they become fashionable,” he said—a remark that became one of his many memorable quotations.

As for other matters of fashion, G. K. Chesterton wore the same outfit for 30 years: a distinctive cape, a nondistinctive shovel hat, and a walking stick that didn’t quite reach the ground from his great height of six feet, four inches. He carried the stick and pointed with it, to tremendous trifles and also to the adorable little universe that everyone else seemed to have forgotten about. He was gigantic and gigantically absentminded. But, as he liked to point out, “absent-mindedness only means present-mindedness about something else.” There is one subject, and his mind was ever on it. He just didn’t know where his train ticket was.

In the opening years of the 20th century, G. K. Chesterton made a large splash in literary London. The Daily News, the paper founded by Charles Dickens, saw sales of its Saturday issue double when Chesterton began writing his weekly column. He was soon hired by The Illustrated London News to pen its weekly “Our Note-Book” column, which he would do for the next 31 years. In the meantime, he was churning out novels, such as The Man Who Was Thursday, and rhetorical delights such as Orthodoxy, an utterly original defense of Christianity that has never gone out of print since it was first published in 1908.

Poet, playwright, novelist, philosopher, critic of art, literature, and society, and creator of the contra-Sherlockian little priest detective, Father Brown—the prolific Chesterton was a true man of letters, who humbly considered himself nothing more than a jolly journalist, with an emphasis on both words. He was a daily observer of life, but his abounding joy and good humor set him apart from his snide and cynical contemporaries, whose ink flowed into the sweeping current of modernism. “A dead thing goes with the stream,” Chesterton remarked, in another of his bon mots. “Only a living thing can go against it.”

Chesterton represented tradition against fashion. “Modern men are not familiar with the rational arguments for tradition, but they are familiar, almost wearily familiar with all the rational arguments for change,” he wrote. But he also represented tradition against “progress.” His critics accused him of trying to turn the clock back, saying it simply couldn’t be done. But Chesterton pointed out (with his walking stick), “Yes, it can!” The clock is our invention. We can set it at any time we choose. (In fact, we unquestioningly turn the clock back once a year.) Civilization is also something we have made. We can remake it according to any plan we please. Which is better than watching it decay. “Every high civilization decays by forgetting obvious things,” he wrote.

Progress, Chesterton pointed out, isn’t anything. You can’t be for progress unless you’ve defined the thing towards which you are progressing. Otherwise progress is simply a comparative for which we have not established the superlative. The Progressives, according to Chesterton, were only interested in “going on towards going on.” Their notion of progress was based on a rejection of the past, a hatred of history, and a breaking of the commandment that tells us to honor our father and mother. Tradition means giving a vote to our ancestors. It is, Chesterton said, “the democracy of the dead.” Letting our ancestors have a vote is only common sense, whereas voting on behalf of our ancestors is election fraud.

For those who would measure progress by technological innovation, Chesterton responded that, in spite of our faster cars and communication, “the mere strain of modern life is unbearable.” The world has become abnormal. We no longer desire normal things: normal marriage, normal ownership, normal worship, or even life itself.

Chesterton is considered a conservative these days, but in his own day he called himself a liberal. He felt that a liberal was someone who believed in freedom. But, just as Ronald Reagan said that he didn’t leave the Democrat Party, it left him; Chesterton said, “I am the last liberal.” He was alienated from Britain’s Liberal Party when he discovered its stealth and corruption, but also when he realized that the Liberals were not interested in liberty or justice; they were only interested in getting reelected.

At the same time, his own brother, Cecil, published an anonymous book arguing that Chesterton’s politics were actually conservative even though he claimed to be a liberal. Chesterton would have none of it. “In practice a conservative commonly means a man who cannot remember anything before yesterday, and a progressive means a man who cannot imagine anything beyond to-morrow,” he wrote. “Both suffer from the unnatural narrowness of supposing that all generations led up to one generation; but for one it is the last generation and for the other the next generation.”

Perhaps he summed up the political dichotomy best with words that are still painfully true:

The whole modern world has divided itself into Conservatives and Progressives. The business of Progressives is to go on making mistakes. The business of the Conservatives is to prevent the mistakes being corrected.

Yet he loved his country and called patriotism a natural virtue, observing that, “In most of the countries most of the Patriots, or most of those who call themselves Patriots, tend to call themselves Conservatives.” But Chesterton was a “Little Englander,” and an open critic of British imperialism, reasoning that one can be patriotic about one’s home, but not about a foreign port you wish to control. As for the popular boast that the sun never set upon the British Empire, Chesterton quipped that he didn’t want a country without sunsets.

His viewpoints proved amazingly influential. One of his Illustrated London News essays critiquing British imperialism inspired Gandhi to begin his movement for Indian independence, thus contracting the British horizon.

Though Chesterton’s friends and family urged him to write more literature and poetry, as the years went on he increasingly focused on politics and social reform. He wrote on those subjects for his brother Cecil’s newspaper, The New Witness, then took over as its editor when Cecil died in World War I. In 1925, he started his own publication, G. K.’s Weekly, which sought to provide an alternative to what we would call the mainstream press, and what Chesterton called the hobbies of a few rich men who happened to control information. “We don’t need a censorship of the press. We have a censorship by the press,” he said.

Chesterton promoted a socioeconomic philosophy that he and his colleague Hilaire Belloc called distributism, which is best understood today as decentralization, or localism. This philosophy recommended widespread small ownership and economic independence as opposed to wage employment. Chesterton recognized government as an evil necessity, but believed that we should keep our politicians close enough to kick them. He really believed in democracy, which is direct rule over government functions by the people, but more importantly in self-rule. Self-government to Chesterton meant freedom, but it also literally meant self-control; it meant restraint, not rebellion.

All of the arguments Chesterton deployed against Big Government he also applied to Big Business or “Hudge and Gudge,” as he dubbed them. He wanted a society based not on individual interests or community interests, but on the interests of the family, which he defined as a small kingdom that makes and loves its own citizens. “The disintegration of rational society started in the drift from the hearth and the family,” Chesterton said. “The solution must be a drift back.”

above: G. K. Chesterton (courtesy of Society of Gilbert Keith Chesterton)

Exactly 100 years ago, Chesterton made his first trip to America, where he lectured to packed auditoriums in over a dozen cities. He lauded the Declaration of Independence and argued that America is the only country ever founded on a creed. However, he pointed out that a nation founded on liberty could not justify anything so ridiculous as Prohibition, which was then in force in the States. At the same time, he said that the pursuit of pleasure is notthe same thing as the pursuit of happiness. “The aim of all human polity is happiness,” he said. “There is no obligation to be richer, or busier, or more efficient, or more productive, or more progressive, or in any way worldlier or wealthier, if it does not make us happy.” The problem with most people, Chesterton believed, is that they don’t know how to enjoy enjoyment.

Today’s conservatives keep dismissing Chesterton’s distributism as a form of socialism, and liberals like to dismiss Chesterton himself as a kind of Catholic fascist. He has also been dismissed by our institutions of higher learning, where he has been purposely kept out of a curriculum that champions everything Chesterton argued against. Yet, he keeps showing up in class. Undergraduate and graduate theses on Chesterton keep emerging, to the embarrassment of professors who don’t know anything about him.

They would probably be horrified if they did know something, because Chesterton pointed out the perils of political correctness and what we now call “cancel culture,” two generations before it inflicted itself on our campuses and elsewhere. Among his observations:

- “The very worst sort of mistakes are those that are not mistakes, but the corrections of mistakes. The worst howlers come from correctness and not from carelessness.”

- “It is always hard to correct the exaggeration without exaggerating the correction.”

- “Those who talk of ‘tolerating all opinions’ are very provincial bigots who are only familiar with one opinion.”

- “A queer and almost mad notion seems to have got into the modern head that, if you mix up everybody and everything more or less anyhow, the mixture may be called unity, and the unity may be called peace. It is supposed that, if you break down all doors and walls so that there is no domesticity, there will then be nothing but friendship.”

- “About all these words men can be morbidly excitable and touchy.”

Chesterton is nothing if not prophetic and quotable. It is these qualities that have naturally led to his recent revival. He tweets well. Here are more of his sayings, which not only speak for themselves, but speak for Chesterton as a stalwart of the right more eloquently than anything we could say about him:

- “The decline of the strong middle class…has left the other extremes of society further from each other than they were.”

- “There will be more, not less, respect for human rights if they can be treated as divine rights.”

- “If you are loyal to anything and wish to preserve it, you must recognize that it has or might have enemies; and you must hope that the enemies will fail.”

- “The aim of argument is differing in order to agree; the failure of argument is when you agree to differ.”

- “A nation is a society that has a soul. When a society has two souls, there is—and ought to be—civil war…. For anything which has dual personality is certainly mad; and probably possessed by devils.”

It was Chesterton’s defense of tradition that led in part to his conversion to Catholicism in 1922, which was a very unpopular thing to do in England. He called it the chief event of his life in The Everlasting Man (1925). It was that book that led a young atheist named C. S. Lewis to convert to Christianity. Lewis recommended it to others as the best popular work on Christian apologetics, and he borrowed its arguments for his own masterpiece of apologetics: Mere Christianity (1952).

In 1932, Chesteron wrote his last great work, St. Thomas Aquinas: The Dumb Ox, which international Thomistic scholar Étienne Gilson called the best book ever written on the Angelic Doctor. Gilson did not stop there; he went on to say:

Chesterton was one of the deepest thinkers who ever existed; he was deep because he was right; and he could not help being right; but he could not either help being modest and charitable, so he left it to those who could understand him to know that he was right, and deep; to the others, he apologized for being right, and he made up for being deep by being witty. And that is all they can see of him.

Image Credit:

above: G. K. Chesterton (courtesy of Society of Gilbert Keith Chesterton)

Leave a Reply