Queen Victoria’s corpse had hardly cooled before modernism in the United Kingdom rebelled against Victorian styles, attitudes, and mores.

The ideas of arguably the four most important thinkers of the modern era—Darwin, Nietzsche, Marx, and Freud—were written during Queen Victoria’s lifetime but only gained influence after her death. So too did the literary high modernists T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, Virginia Woolf, Gertrude Stein, and D. H. Lawrence quickly overshadow the Victorian era’s favorite novelists such as Thomas Hardy, Henry James, Joseph Conrad, Rudyard Kipling, and H. G. Wells. James Joyce became the figurehead of modernism in Ireland, which experienced a literary revival under William Butler Yeats, John Millington Synge, and George Bernard Shaw, while William Faulkner rose to prominence in the United States.

The world, however, continued turning; the high modernists, once aesthetic subversives, had rigidified into the new establishment in the postwar era.

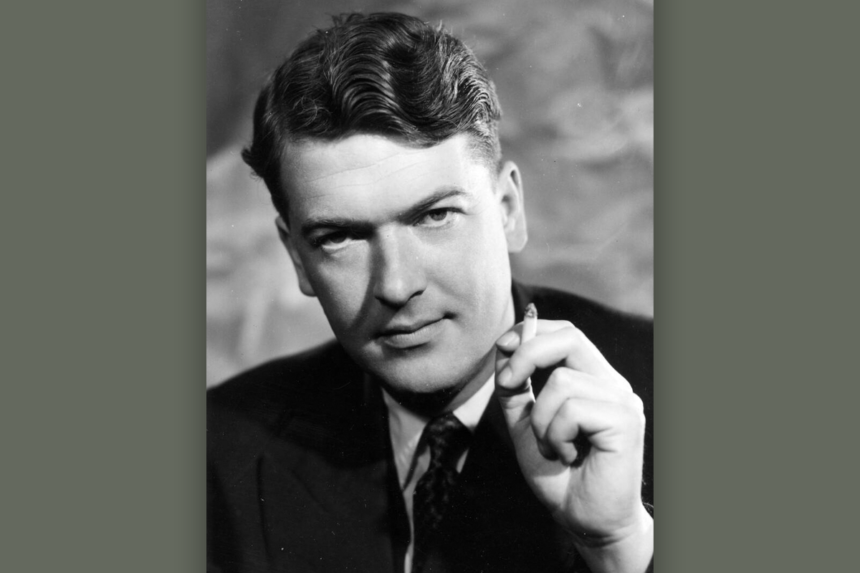

Enter Kingsley Amis: Born in 1922, Amis satirized the modernists, authoring dozens of books in ordinary idiom and without modernism’s avant-garde displays of stream of consciousness, inner monologue, obscurantism, abstraction, and ambiguity. Amis attained celebrity in the 1950s as one of the so-called “Angry Young Men,” along with playwrights and writers such as John Osborne, Alan Sillitoe, and John Braine, who lambasted the status quo for ossifying barriers to entry into high society and prestigious positions. Amis and Braine gradually moved politically to the right as they aged, appearing together on William F. Buckley, Jr.’s Firing Line television program in 1970.

Amis was a first-generation college student who claimed to have quit driving in the 1940s. Although accomplishing fame and notoriety as a young rebel, he became, with his sartorial conservatism (vests and tweed jackets), crusty demeanor, and adamant political incorrectness, a picture of ages past. Class issues were foremost in Kingsley’s mind, even as the intelligentsia that had grown up around him looked increasingly multicultural and prioritized issues of race, sexuality, and gender.

While a student at Oxford in 1941, Amis joined the Communist Party from which he would loudly disassociate in 1956 after Khrushchev denounced Stalin. Allegedly, one reason he joined the Communist Party was to discover girls who practiced free love. He struck up a friendship with Philip Larkin at Oxford and dedicated one of his most popular novels, Lucky Jim (1954), to him. Larkin helped Amis develop the novel’s characters based on real people they knew. Amis liked to say that he and Larkin flipped places; Amis sought success as a poet but found it as a novelist, while Larkin sought success as a novelist but found it as a poet.

above: book cover for Lucky Jim by Kingsley Amis (NYRB Classics)

Amis was not religious. He was a serial philanderer whose famous humor won him many carnal pleasures. His first wife, Hilary Ann, relished her own fair share of affairs. Kingsley didn’t mind so long as the adultery cut both ways. His second wife, the novelist Elizabeth Jane Howard, was a Tory of low birth. Kingsley admired Margaret Thatcher, who likewise scaled Britain’s social hierarchy through hard work and intellectual merit.

Amis was an alcoholic who loved writing about drinking as much as he loved drinking. He credited P. G. Wodehouse and Evelyn Waugh as influences and disliked modernism for its radical experimentation, which he dismissed as unnecessarily difficult and pretentious. He wrote with plain diction but acrobatic syntax, both in poetry and prose, and poked fun at pompous, ostentatious figures who put on airs and affected cultural superiority while demonstrating a general lack of intelligence.

Amis was such a performer that the British public associated him with Jim Dixon, the quintessential antihero of Lucky Jim, whose persona Amis adopted for the attention it drew. The novel’s critics have treated Jim as an avatar of Amis himself, and for good reason. Like Jim, Amis identified with working-class culture and was out-of-place in the aristocratic, elitist milieu of academia. Like Jim, Amis taught at a university but grew disenchanted with the ivory tower and quit the faculty of the University of Swansea to write full time. And, like Jim, who served in the Royal Air Force but never saw combat, Amis served in the British Army before embarking on his career.

Jim, unremarkable in appearance and with poor etiquette, possesses a keen eye for social and class distinctions. He loathes hypocrisy, affectation, silliness, pretension, and snobbishness. He bumbles from misadventure to misadventure, drinking and smoking and, alas, winning over a girl whom he believed to be out of his league. Jim and the novel represent the upstart and the uncultivated against stuffy, highbrow, and pedantic society. Not for him the arrogant, humorless pedants of his provincial university. He mouths socialist platitudes and declares solidarity with the poor, as Kingsley had at that age.

Jim isn’t what you’d call a gentleman. He lacks manners and taste, he cusses and can’t read music, and he makes faces (his Eskimo face, his Martian invader face, his Chinese mandarin face, his lemon-sucking face, and so on) as mimetic performances to express his feelings. Only readers, not the characters in the novel, enjoy access to Jim’s mind and know why he chooses a particular look. Jim feels the need to match his external countenance with his internal emotions.

Jim isn’t interested in medievalism, his chosen academic field, and he pushed his way into his job by emphasizing that he had studied under a prominent medievalist. He’s less equipped, however, than the eager and annoying male student Michie to comment upon medieval subject matter. He fears he will be fired because he’s a junior lecturer on a two-year probation contract and can’t get the only article he’s written published in a learned journal.

Although Lucky Jim, a campus novel, is but one piece of Amis’s vast oeuvre, it is arguably the most important, and one that reveals much about Amis the man. Told by a third-person narrator who shares Jim’s perspective and derisive attitude and who knows Jim’s thoughts, Lucky Jim is as much about characters as it is about plot.

The plot is humorous, straightforward, and linear, centering on three scenes: the arty weekend at the Welches’ home (Professor Welch, a caricature of the snobbish, aloof professor type, is Jim’s department head, and his wife is a mean and absurd Francophile), the Summer Ball, and the Merrie England lecture.

Jim is trapped in his academic microcosm and eventually escapes his sorry lot through happenstances arising out of unfortunate events that unexpectedly culminate in a happy ending—hence the novel’s title, Lucky Jim. He moves from passive to active, weak to strong: at the novel’s opening he’s a helpless passenger in Welch’s car, but gradually he achieves agency until, at last, he outwits the Welches and his other opponents and succeeds in his pursuit of the 22-year-old Christine, whose name means “follower of Christ” (she saves Jim).

Welch and his son, Bertrand, epitomize everything Amis abhorred about modernism. Welch professes to love art and music but is ridiculous in his manifestation of that love; to his credit, however, his taste for music is classical in the vein of Brahms and Mozart. He asks Jim to give the “Merrie England” speech. “Merrie England,” of course, is an idealized pastoral England lacking monarchical violence and emphasizing a romanticized version of nature and of literary and legal culture before the Industrial Revolution. Welch condescends to his supposed inferiors and coerces Jim to edit and research for him; he equivocates and remains noncommittal when Jim confronts him about continued employment at the school.

Like the effect of modernist art and literature, Welch’s speech causes confusion and disorientation; when he instructs Jim to locate sources in the library, he fails to mention that he means the public library and not the university library, which, because it’s only a few feet from where Jim and Welch stand, Jim naturally presumes is Welch’s referent. During the arty weekend, Jim leaves the Welches’ party, which is full of pretense and airs and silly singing—and, for heaven’s sake, no alcohol—for the rustic and vulgar pub, where he proceeds to get hammered. He doesn’t feel that he belongs at the party, and his absence is scarcely noticed.

Bertrand, who aspires to be a renowned artist, is far more malicious than his father. He calls Jim a “lousy little philistine,” “a dirty little barfly,” and a “nasty little jumped-up turd.” He speaks with manufactured inflections that make him seem preposterous, pronouncing “see” as “sam” as in “you sam” (or “me” as “mam”). He’s a painter and a pacifist with a long beard who wears a loud yellow sport coat and a beret. At one point Dixon pretends to be a reporter calling from the Evening Post. He asks Bertrand about his paintings, and Bertrand talks about three works-in-progress, including a self-portrait and the painting of a nude female that he labels “modern.”

Bertrand comes across as upper class and pro-rich, disdainful of the masses and lower classes; he criticizes the welfare state and social safety nets. Christine, his girlfriend, has never seen his paintings. Her role in the relationship appears not-so-curiously related to her uncle, Julius Gore-Urquhart, a wealthy Scottish patron, probably in his 40s. Bertrand hopes to gain a job as Gore-Urquhart’s personal assistant. Jim triumphs by seizing not only Bertrand’s girl, Christine, but also Bertrand’s dream job working for Gore-Urquhart. The common man defeats the antiquarian elites. Jim’s and Amis’s antiestablishmentarianism prevails.

Amis remained antiestablishment his entire adult life. The establishment, however, changed from conservative in the 1940s and 1950s to progressive liberal in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s. Amis was decidedly anti-Marxist and anti-Communist during the Cold War and supported the Vietnam War. He complained that universities bloated with students and faculty produced a diminished quality of ideas and thought. The democratization of academia signaled, to his mind, a decline in excellence and merit.

Having published The James Bond Dossier in 1965 using the pseudonym Robert Markham, a year after Ian Fleming’s death, Amis followed up with the first Bond novel to be published by someone other than Fleming. In 1967, he penned the essay “Why Lucky Jim Turned Right” for the Sunday Telegraph, writing in the persona of the character Jim Dixon. In the essay, Amis cited the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 as a catalyst for his abandoning the left, along with education policies that, he insisted, lowered standards. “I am not a Tory,” he clarified, “nor pro-Tory … nor Right wing, nor of the Right, but of the Centre, opposed to all forms of authoritarianism.”

above: book cover for The James Bond Dossier by Kingsley Amis (New American Library)

During his final years, Amis moved in with Hilary, his first wife, and her husband Alastair, who was born into an aristocratic family but had little wealth himself. This arrangement saved Amis’s children from having to “babysit” their father. Amis liked it because he couldn’t stand to be alone; he was constantly in need of conversation—and drink.

Amis became known, affectionately, as “Sir Kingsley” after he was knighted in 1990. He left this world a Bohemian conservative who despised dogmas of all sorts, and an insider whose reputation depended upon his being an outsider. Since his death, he’s been charged with the typical modern allegations of anti-Semitism, homophobia, and misogyny—accusations that shouldn’t stop readers from reading his books on their own terms and with appropriate historical context.

The left detested Kingsley as he aged. Why? This quote from Matthew Walther in The American Conservative sums it up: “[Amis] hated tolerance, diversity, foreign languages, airplanes, popular music, all female novelists—save perhaps Dame Agatha Christie—bebop and modal jazz, being alone, art cinema, purchasing gifts for his wives, the Arts Council of Great Britain, homosexuals, America, defenders of communism, gardens, and the dark.” Amis deplored, in his own words from his 1967 essay, “Leftys” who buy “unexamined the abortion-divorce-homosexuality-censorship-racialism-marijuana package.”

One socialist’s obituary of Amis repeatedly refers to him as a “reactionary” and discourages the reading of his books. A scribbler for British labor causes, Owen Jones, accused Kingsley’s son Martin Amis, a momentous writer himself, of being a “snob” who grew up with “privilege.” One can picture Sir Kingsley, like Jim, drawing in his breath to denounce these blatherskites, but then blowing it out again in a howl of laughter.

Ah, Lucky Kingsley. His body of work and the evolution of his politics should teach today’s conservatives not to judge young lefties too severely; for anyone’s views can change.

above: Kingsley Amis, English novelist and poet, c.1956 (Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo)

Leave a Reply