An Architect of America’s Common Good

On the 18th of July this year Catholics celebrate the 700th anniversary of the canonization of St. Thomas Aquinas. The scope of thought produced by this universally admired, erudite teacher, who was called the Doctor Communis (“the Common Doctor”), and his continued importance to the whole of Western philosophy, can scarcely be exaggerated. Less appreciated, perhaps, is how his notion of the “Common Good” contributed to America’s founding ideas, more than 500 years after his death.

Aquinas was able to sum up and distill the whole of human discourse, from poetry, through natural philosophy and logic, through ethics, politics, and anthropology and psychology, to metaphysics and theology. He treated all of these subjects in the light of both the rational patrimony of Greek and Roman philosophy and the light of biblical revelation. As a result, he has held a high place in the study of every serious student of philosophy and Western civilization—including in the education of America’s Founding Fathers. And, as I will argue, his notion of the proper end of the state found its way into their conception of the American republic.

Thomas was born in the Campagna region of the southern end of the Italian Peninsula in 1250, the son of Landulf of Aquino, of the ancient and still-existing Neapolitan noble family of the name. Landulf was politically very close to the party of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II. Landulf’s brother Sinibald was the abbot of Montecassino, where Thomas was sent at the age of five to begin his education and formation as a monk, in line with his family’s ambition that he succeed Sinibald as abbot of the immensely powerful and influential abbey, which was founded by St. Benedict himself.

Benefitting from the progressive intellectual climate under Frederick, so different from the traditionalist style of education then practiced in Paris, Thomas was sent to Naples, where the Greek philosophers and the Aristotelian corpus of natural philosophy were studied freely in public lectures. His tutor, Peter the Hibernian, was a devoted exponent of Aristotle’s philosophy of nature. The recently founded Order of Preachers, the Dominicans, also took advantage of the academic liberty available under imperial protection in Naples, and taught and studied Aristotle’s corpus.

Thomas came to know the Dominicans and determined to join them. This caused several years of dispute within his family, who were loath to lose the abbacy of Montecassino as a result of his ambition to join the mendicant order of the Dominicans, which was outside the established monastery system. He was abducted by his own family and held under house arrest for nearly a year in their castles; his brothers even tried to break his will by hiring a prostitute to seduce him, but he drove her away. Finally, Thomas’ mother relented and secretly allowed him to escape from his confinement, saving his parents the embarrassment of a public renunciation of his patrimony.

The Dominicans sent him to Cologne, where he studied with Albert the Great, his most influential teacher and mentor. The rest of his short life was spent in an awe-inspiring and unparalleled production of scriptural and philosophical commentaries, comprehensive works on theology, disputed questions, as well as poetry and correspondence. This was carried out at Paris, Orvieto, Rome, and Naples. He died in 1274, aged either 48 or 49, on his way to the Second Council of Lyon, after an accidental blow to the head, which perhaps resulted in internal bleeding.

Yet perhaps for the reader of this magazine, Aquinas is best known for his political thought. Let us consider this aspect of his work as we recall his glorification by Pope John XXII at Avignon of Provence in 1323.

Aquinas viewed as legitimate a number of polities, from monarchy to aristocracy to a parliamentary republic. Although he often spoke of the king and his duties, it is clear that he thought that monarchies as well as governments that are collegial or representative are to be understood in terms of a common standard of justice.

What is most telling about Aquinas’s understanding of the constitution of states, however, is the metaphysical quality that he attached to the most fundamental principle of government; namely, that there is a Common Good as the end and transcendent context of human political society.

Let us take a look at this teaching, which is not the banal, socialist, moralizing notion of the Common Good, which one finds among social democrats on either side of the Atlantic. Much less is it the materialistic and totalitarian notion of atheistic socialism, but rather a vigorous assertion of a destiny and an end for human endeavor which is barely hinted at by current notions of freedom of choice and political empowerment. Its fulfillment is not in worldly freedom, but in freedom’s sublimation to the ultimate end, which renders freedom irrelevant except as a past necessity; that is, the Common Good of eternal salvation.

In order to do this, we must first examine our own American notions of the end of political life. There are surprising points of convergence between Aquinas and our own authoritative national tradition, even as we note the more mundane claims of our own laws when compared to Aquinas’s lofty goal of eternal life!

Our nation has a number of founding documents, some legally binding, like the Constitution, others indicative of original intent, like the Declaration of Independence, or subsequent reinterpretations, like the Gettysburg Address. They all have appropriately grand openings: “We the people,” “When in the course of human events,” “Four score and seven years ago, our fathers…” In the case of the first of these, the opening words provide a context, which is not only historical but essential to the legal validity of the document.

There is, however, another less-often-considered American founding document whose opening words have a similar weight. I am referring to the Treaty of Paris, marking the occasion when America became fully a new nation in the eyes of all the world.

As an American of a particular stripe—that is, as a sacramental, Chalcedonian Christian, a disciple of St. Thomas Aquinas, and a physical descendant of the generations that shared personally in America’s founding events—I have always favored the Treaty among the founding documents, and it is arguably the most definitive. Signed on Sept. 3, 1783, it marks the absolute end of the War of Independence and the entrance of our new republic into the family of nations.

Compare the exordium of this document with the Declaration, its principle, and its description of fundamental motives, which run deeper than political freedom and redress of wrongs:

In the Name of the Most Holy and Undivided Trinity: It having pleased the Divine Providence to dispose the Hearts of the most Serene and most Potent Prince George the Third, by the Grace of God, King of Great Britain, France, and Ireland, Defender of the Faith, … etc. and of the United States of America, to forget all past Misunderstandings and Differences that have unhappily interrupted the good Correspondence and Friendship which they mutually wish to restore…

An affective trajectory defines the movement of this passage: the mysterious inner life of knowledge and love in God, One and Three, his intention to move, “dispose” similarly, that is, by knowledge and love, “providentially,” the movements of the inner life, “the hearts” of the king and of his former subjects, the citizens of the United States of America, to pardon, to “forget” their past offenses, and to recover, “restore” their mutual affection, their “friendship.”

Divine Life and Mystery, God’s efficacious grace moving human hearts to forgiveness, good will, and friendship: in short, all of the essential elements of human moral perfection and happiness, these provide the context of the Treaty of Paris whereby the independence and sovereignty of the United States of America are established in perpetuity.

It is not too much to interpret this opening statement of the treaty closely in terms of its moral and theological premises. The events it brings to final resolution were far too specific and historically momentous, indeed unique, for the evocation of the Trinity and the motive power of a sovereign grace, and perseverance in mutual love and pardon to be a merely rhetorical embellishment. After all, this is a legal document. Since we parse meticulously every turn of phrase and nuance of our Constitution for its original intention, surely this definitive treaty deserves a similar treatment, even if its theological assertions exceed the usual scope of our juridical and political discourse. After all, this treaty ratified our independence before the world.

Perhaps most importantly, the treaty also shows that the American nation was one based on the religion of the Old and New Testaments.

The Thomist might add that independently of any private judgments, the nature and end of human political society is to be understood as ordered ultimately by principles that transcend it. We might also ask whether the “Nature and Nature’s God” mentioned in the Declaration of Independence is not also a reference to “the Supreme Judge of the World.”

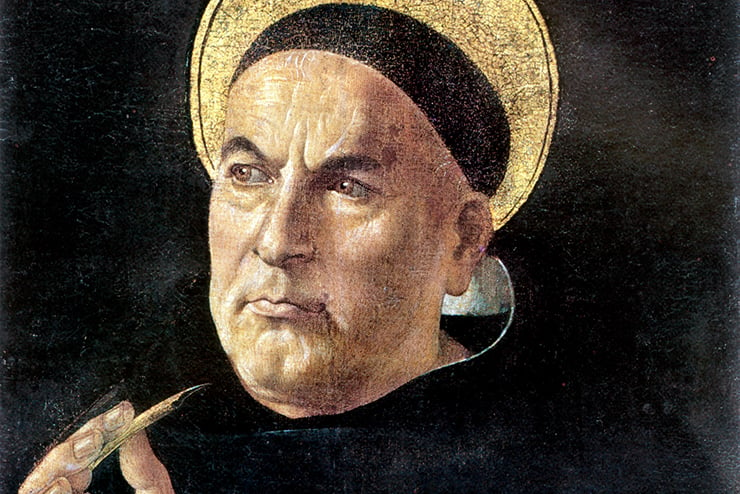

(London National Gallery)

Now to honor our long-canonized teacher, let’s take a look at some of Aquinas’s assertions that are congruent with the opening lines of the Treaty of Paris. A careful reading of these passages, dense as they are, should reveal the sublime end of things political.

The restoration and maintenance of “Friendship”—that is, of the particular and privileged form of love which binds one man to another, even to the laying down of his life—is the most solid foundation of the state. St. Thomas told us this with schematic lucidity in his Quaestiones disputatae: De caritate (Disputed Questions on Charity):

It must be said that since love looks to the good, there is a diversity of love according as there is a diversity of the good. There is, however, a certain good proper to each man considered as one person, and as far as loving this good is concerned, each one is the principal object of his own love. But there is a certain common good which pertains to this man or that man insofar as he is considered as part of a whole; thus there is a certain common good pertaining to a soldier considered as part of the army, or to a citizen as part of the state. As far as loving this common good is concerned, the principal object of love is that in which the good primarily exists; just as the good of the army is in the general, or the good of the state is in the king. Whence, it is the duty of a good soldier that he neglect even his own safety in order to save the good of his general. Thus also does a man naturally endanger his arm in order to save his head. And in this way charity regards the divine good as its principal object, which pertains to every one according as he is able to be a sharer in beatitude; thus we love out of charity only those objects which are able to participate in eternal happiness with us, as Augustine says in the De Doctrina Christiana.

This mutual love, Aquinas wrote, rooted in the hope of a future commonly possessed happiness, is the substance of what leads men into the possession of blessedness. This is so since our eternal reward stems from our struggle to maintain the Common Good of friendship. St. Thomas shows the hierarchy of loves and the corresponding title to a reward for those who care for the good of human society. He also states this in terms of the reward due to a just king, but his formal assertions about monarchy can apply to leaders of other forms of government who care just as diligently for the commonweal. He writes in De Regno (On Kingship):

Now it remains further to consider that they who discharge the kingly office worthily and laudably will obtain an elevated and outstanding degree of heavenly happiness.

For if happiness is the reward of virtue, it follows that a higher degree of happiness is due to greater virtue. Now, that indeed is signal virtue by which a man can guide not only himself but others, and the more persons he rules the greater his virtue. Similarly, in regard to bodily strength, a man is reputed to be more powerful the more adversaries he can beat or the more weights he can lift. Thus, greater virtue is required to rule a household than to rule one’s self, and much greater to rule a city and a kingdom. To discharge well the office of a king is therefore a work of extraordinary virtue. To it, therefore, is due an extraordinary reward of happiness.… The greatness of kingly virtue also appears in this, that he bears a special likeness to God, since he does in his kingdom what God does in the world; wherefore in Exodus 22:9 the judges of the people are called gods, and also among the Romans the emperors received the appellative Divus. Now the more a thing approaches to the likeness of God the more acceptable it is to Him. Hence, also, the Apostle urges (Eph 5:1): “Be therefore imitators of God as most dear children.” But if according to the saying of the Wise Man (Sirach 13:9), every beast loves its like inasmuch as causes bear some likeness to the caused, it follows that good kings are most pleasing to God and are to be most highly rewarded by Him.

Perhaps in today’s world it sounds absurd to say that the politician is a god-like figure whose faithful performance of his office deserves a god-like reward. But the logic of this teaching is patent, granted that we hold that purity of intention and the pursuit of the good are operative in a political career. We may assume that the framers of the Treaty of Paris would not have denied this conclusion.

Normally when conservative writers treat St. Thomas’ political theory they write mostly of his notion of the natural law. They focus on the rational accessibility of the natural law, which of course they acknowledge as coming from God. Yet Aquinas’s notion of the natural law is ultimately theological insofar as the natural law is our reason’s participation in the eternal law of God, which issues from the Divine Mind itself. As Aquinas writes in the first part of the second part of his Summa Theologica:

Law, being a rule and measure, can be in a person in two ways: in one way, as in him that rules and measures; in another way, as in that which is ruled and measured, since a thing is ruled and measured, in so far as it partakes of the rule or measure. Wherefore, since all things subject to Divine providence are ruled and measured by the eternal law, as was stated above (Article 1); it is evident that all things partake somewhat of the eternal law, in so far as, namely, from its being imprinted on them, they derive their respective inclinations to their proper acts and ends. Now among all others, the rational creature is subject to Divine providence in the most excellent way, in so far as it partakes of a share of providence, by being provident both for itself and for others. Wherefore it has a share of the Eternal Reason, whereby it has a natural inclination to its proper act and end: and this participation of the eternal law in the rational creature is called the natural law.… It is therefore evident that the natural law is nothing else than the rational creature’s participation in the eternal law.

This means that the least use of our reason in deciding what we are to do morally is a participation in a judgment that is eternal. There can be scarcely any higher dignity that can be ascribed to human agency than this. This is especially true when the judgments are given by upright men who have the care of the Common Good. Such were the Founding Fathers of our Republic. Their reward is undoubtedly great, as great was their love of neighbor in friendship under the providential movement of the grace of God. They cast off a king, but not a king’s reward.

(This “Remembering the Right” features will appear in the August print edition of Chronicles.)

Leave a Reply