The Sage of Chelsea

Thomas Carlyle, the Sage of Chelsea, was neither a liberal nor a democrat, but he was also not a “small c” conservative who believed gradual reform was either desirable or possible, at least not in the lineage of Edmund Burke or Russell Kirk. While Carlyle was a kind of perennial traditionalist, he was not afraid of drastic change or even revolution if a ruling class had become too corrupt or too decadent to serve.

If Burke’s chief lesson from the French Revolution was to avoid revolutions at all costs, Carlyle saw change, even violent change, as being sometimes necessary and sometimes, as for Heraclitus, an all-consuming and purifying fire. If people feel abandoned or betrayed by their rulers, then history—which for Carlyle had a spiritual dimension—will find a way to cleanse and punish the “corrupt worn-out Authority.” Social energies will coalesce around a hero, a man of action, one who is resolute, steady, and uncompromising, embodying the “Everlasting Yea,” driven as if by divine providence to restore the moral and political orders. “The History of the world,” wrote Carlyle in On Heroes, Hero Worship, and the Heroic in History (1841), “is but the Biography of great men.”

For Carlyle, what had gone wrong in England after the Industrial Revolution was not a matter of mere policy but a deep spiritual malaise in which a morally bankrupt and deadening economic utilitarianism had come to suffocate any sense of the heroic or transcendent. As he put it in his 1829 essay, “Signs of the Times,” he lived in an “Age of Machinery, in every outward and inward sense of that word.” He yearned for “the primary unmodified forces and energies of man, the mysterious springs of Love, and Fear, and Wonder, of Enthusiasm, Poetry, Religion, all which have a truly vital and infinite character.”

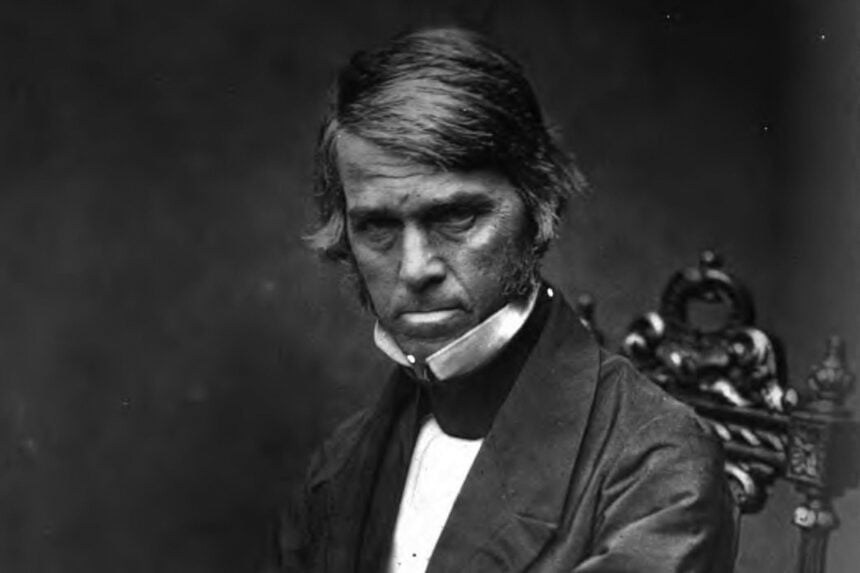

(photograph by Elliott & Fry)

Carlyle was a man of many contradictions: profoundly religious yet a kind of atheist (“Calvinism without the theology” as his biographer James Anthony Froude famously put it); vehemently opposed to free market economics yet a supporter of the repeal of the Corn Laws; passionately concerned for the poor and downtrodden yet resolutely opposed to both democracy and the abolition of slavery; at once somehow lofty and prophetic yet stubbornly down-to-earth; admired by many socialists—including, among others, John Ruskin, Karl Marx, and Friedrich Engels—yet unmistakably a man of the right, committed to hierarchy and social order.

Few writers in history have thundered on the page—all fire and brimstone—quite like Carlyle, yet he was never straightforwardly didactic: his work is littered with wry allusions, biting humor, irony, subtle sarcasm, rhetorical invective, and framing devices that today would be called postmodern.

His 1831 novel, Sartor Resartus (“The Tailor Re-tailored”), is best described as an “anti-novel,” which is fitting because he hated fiction. John Stuart Mill described Carlyle’s best-known and best-loved history, The French Revolution (1837), as “not so much a history, as an epic poem.” Or as another commentator, John Rosenberg, has put it, “Carlyle writes as if he were a witness-survivor of the Apocalypse.” His bombastic style was so idiosyncratic that it was dubbed “Carlylese” and was described memorably by William Makepeace Thackeray: “It is stiff, short, and rugged, it abounds with Germanisms and Latinisms, strange epithets, and choking double words, astonishing to the admirers of simple Addisonian English.” G. B. Tennyson later wrote of Carlyle’s style that “not until [James] Joyce is there a comparable inventiveness in English prose.”

An excellent introduction to Carlylese would be to read any of the essays in Latter-Day Pamphlets (1850), a volume in which he deliberately dialed up his rhetoric to near self-parodic levels. Consider “Model Prisons,” for example, in which Carlyle takes a tour through a new Victorian prison and laments the fact that conditions are much too comfortable and forgiving for the inhabitants inside. Outside is a London inhabited by “Solemn human Shams, Phantasm Captains, and Supreme Quacks that ride prosperously through every thoroughfare.” And inside the prison we meet

miserable distorted blockheads, the generality; ape-faces, imp-faces, angry dog-faces, heavy sullen ox-faces; degraded underfoot creatures, sons of indocility, greedy mutinous darkness, and in one word, of STUPIDITY, which is the general mother of such. Stupidity intellectual and stupidity moral … had borne this progeny.

This searing, incessant and relentless piling up of images in a great moral tumult echoes that of a firebrand preacher. Carlyle embodied the voice of the prophet. In many respects, his unheeded warnings have since come to pass to such an undeniable degree that it is as if he is stepping through time to speak directly to us in the 21st century. If Carlyle thought things were bad in 1850, imagine what he would make of 2022!

Of his biography, one need only know that he was Scottish, born in the village of Ecclefechan in 1795, raised by devout Protestant parents, attended Edinburgh University, and lost his Christian faith as a teenager after reading The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire by Edward Gibbon. Carlyle once remarked, “I do not in the least believe that God came down upon earth and was a joiner and made chairs and hog-troughs; or came down at any time more than He comes down now into the soul of every devout man.”

Carlyle broke off plans to join the ministry in 1817 and reluctantly became a mathematics teacher for a period. He married Jane Baillie Welsh in 1826. The details of their tumultuous 40-year relationship continue to titillate the vapid British media to this day. For example, Frances Wilson writes in The Spectator,

For some, he was the victim of a shrew who mockingly recorded his every gesture; for others she was the victim of a brute who failed to see her brilliance. “Being married to him,” said Jane’s friend Anna Jameson—having just braved the consequences of interrupting the sage in one of his monologues—must be “something next worse to being married to Satan himself.” Samuel Butler refused to take sides. “It was very good of God to let Carlyle and Mrs. Carlyle marry one another,” he quipped, “and so make only two people miserable and not four.”

They moved from Scotland to 5 Cheyne Road, Chelsea, in London in 1834; one can still visit the house where they lived, which has been kept as it was. Carlyle would remain there for the rest of his life.

In the intermediary years, he had immersed himself in contemporary German literature—at that time, the works of Friedrich Schiller, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and Jean Paul Friedrich Richter. It was primarily because of Carlyle’s Life of Friedrich Schiller (1825) and his translations of Goethe and other German writers that he secured a regular income from writing articles on literature and history for Fraser’s Magazine from 1830 onwards. Almost all of Carlyle’s output between 1830 and 1841 appeared first in Fraser’s; the books were published in serial form and then later released in their own volumes.

However, in 1841, the owner of the magazine, James Fraser, who had been a major champion of Carlyle’s, died. Carlyle took on a new publisher, Chapman & Hall, who bought the rights to all his previous works and remained his sole book publisher until his death in 1881, although he continued contributing articles to Fraser’s. This was partly because he wished to deal with as few publishers as possible; he wrote in 1842, “I avoid all Booksellers; see them rarely, the blockheads; study never to think of them at all.”

Carlyle was arguably Britain’s most revered literary figure in the 19th century; Ralph Waldo Emerson called him “the undoubted head of English letters.” He was almost certainly the best connected. He had either correspondence or personal friendships with, among countless others, Goethe, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Mill, Emerson, Tennyson, Robert and Elizabeth Browning, Ruskin, Dickens, Thackeray, Gaskell, Trollope, Whistler, Chopin, and Darwin, as well as Prime Minister Robert Peel and French President Louis Napoleon. By the time of Carlyle’s death, in 1881, he had been interviewed by Queen Victoria and refused a knighthood offered by Benjamin Disraeli. His books also sold in large numbers for the time period, with each of his major titles selling tens of thousands of copies annually up to 1901. He was widely read and quoted by educated people across Europe and America, enjoying particular popularity in Germany.

Carlyle is also one of the few men in history to have influenced both Karl Marx and Adolf Hitler. Friedrich Engels, coauthor with Marx of The Communist Manifesto, commented while reviewing Carlyle’s Past and Present that the “book is ten thousand times more worth translating into German than all the legions of English novels.” Nazi Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels reputedly read excerpts of Carlyle’s Frederick the Great (1865) to Hitler in his bunker and reported in his diaries that “the Führer had tears in his eyes.” The Nazis had also made On Heroes compulsory reading in school curricula. Because of these associations, Carlyle fell out of fashion after World War II, especially after J. Salwyn Schapiro, a prominent professor at the City College of New York, had labeled him “The Prophet of Fascism.”

Carlyle’s reputation, once soaring and eliciting comparison with Shakespeare, has suffered because of the West’s hysterical reaction to fascism and to Carlyle’s perceived influence on it, although this demonization has somewhat abated in recent years. While he is not read as widely now as he had been before the war, by the early 1970s, Carlyle had been largely rehabilitated inside the academy. There have been at least four major biographies since 1974, a dozen or so monographs, hundreds of journal articles, and major scholarly editions of his works published by university presses.

It is still common to see Sartor Resartus, Past and Present, On Heroes, or shorter works such as Chartism (1839), “Characteristics” (1831), or “Signs of the Times” as set reading in many Victorian literature courses. This is perhaps surprising given the abject state of the modern academy and the fact that Carlyle was an avowed and unapologetic racist, but his inclusion is also testament to his importance to the social debate of the period.

We still feel his influence on that debate now, if indirectly. When many people think of Victorian London, their minds likely imagine a scene from a Charles Dickens novel, but as Dickens wrote in an 1863 letter to Carlyle, “I am always reading you faithfully, and trying to go your way.” The influence is especially marked in Dickens’s more pessimistic later work, such as Hard Times (1854), which was dedicated to Carlyle, and A Tale of Two Cities (1859), which was directly inspired by Carlyle’s French Revolution.

Carlyle’s impact on how we think about the Victorian era is so marked that even the language with which we describe the period was often coined by him. For example, Carlyle was the first writer to use the word “industrialism” or the phrase “captains of industry” to describe industrial tycoons of the day; “the Condition of England Question” to describe the living conditions of the working classes; “cash nexus” to refer to the reduction (under capitalism) of all human relationships to monetary exchange; and “the dismal science” to refer to the field of economics.

Carlyle has also gained an unlikely online following in recent years, owing chiefly to two key sources. The first is a widely circulated lecture on Carlyle delivered by the late British nationalist Jonathan Bowden in 2008 at a meeting of the London New Right. Carlyle, said Bowden, was “shooting arrows into the future.” The second is the blog Unqualified Reservations authored by Curtis Yarvin, also known as Mencius Moldbug, who “rediscovered” and popularized Carlyle’s social and political thought, much to the chagrin of libertarians. “I am a Carlylean,” Yarvin declared in his idiosyncratic style. “I’m a Carlylean more or less the way a Marxist is a Marxist. My worship of Thomas Carlyle, the Victorian Jesus, is no adolescent passion—but the conscious choice of a mature adult.” Carlyle has thus become central to the nascent movement known as Neoreaction.

Carlyle never wrote any systematic treatise of philosophy. His works, however, can be divided into three main categories through which he developed his thought: literary review, history, and social commentary. His early career, encompassing the 1820s, is marked by his interest in German literature and the influence of Schiller and Goethe. This may be called his Romantic period, the culmination of which came in the form of Sartor Resartus, his strange anti-novel.

In Sartor Resartus, an English editor struggles to understand the life and work of a German professor called Diogenes Teufelsdröckh, who is a “philosopher of clothes.” The editor muddles through a fictional manuscript, Die Kleider (“The Clothes”), on the origin and influence of clothes before giving some details of Teufelsdröckh’s life and outlining his philosophy. Still a bizarre and beguiling text, Sartor Resartus can be read as an attempt to confront an empirically and materially minded British audience with German transcendental idealism. It was his best-selling book during his lifetime and sold over 75,000 copies during that period.

But Carlyle became a major literary figure primarily as a historian with the publication of The French Revolution in 1837. Dickens would reportedly lug around the three-volume work with him wherever he went and claimed to have read it 500 times. It remains a blistering account of those terrifying years of French history—almost like a cinéma verité documentary. Carlyle drew his material from hundreds of contemporary newspaper articles, pamphlets, gossip sheets, and anecdotes in order to bring the history to life. Where the antiquarian historian aimed to be objective, Carlyle was opinionated; where the antiquarian historian wrote in neat and arid prose, Carlyle set the page afire with all his rhetorical vigor. Even the mundane scholarly work of sharing sources is brought alive by Carlyle; imagine a typical historian setting up a reference quotation like this: “I may as well print the little Note, smelted long ago out of huge dross-heaps in Noble’s Book.”

His second masterpiece of history, Oliver Cromwell’s Letters and Speeches (1845), starts with an all-out assault on the hated conventional historian, whom Carlyle dubs “Dryasdust”: “Dull Pedantry, conceited idle Dilettantism,—prurient Stupidity in what shape soever,—is darkness and not light!”

Carlyle’s basic idea of history as being primarily the deeds of great men is outlined in On Heroes. It should be noted that the modern liberal order detests this idea and seeks to explain away such figures as Caesar, Cromwell, Napoleon, Washington, de Gaulle, Frederick the Great, and so on as being mere functions of structure or economic forces. This is not a simple debate over historiography; there is a deep metapolitical dimension to the banishment of the theory of the Great Man from polite discourse. The heroic is a genuinely terrifying idea to the liberal mind, which must seek to make everything petty and small. At present, we witness countless liberal publications attempting to account for Vladimir Putin by means of amateur psychologizing. “He’s gone mad!” they shriek—but this is only because the notion of a Great Man who holds the destiny of his nation in his hands is foreign to the left’s worldview. They cannot even process such a notion, which is why every attempt has been made to confine Carlyle to the dustbin of history.

Today, however, many readers will find even greater interest in Carlyle’s social and political writings. Starting with “Signs of the Times” and developing through “Characteristics,” Chartism, Past and Present, “The Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question,” Latter-Day Pamphlets, and “Shooting Niagara and After?” the core of his political thinking does not change in the nearly 40-year span, but his attitude becomes darker and more severe and less hopeful over time.

The basic Carlylean thesis—which was inherited almost wholesale by many later conservatives who stood against capitalism—is that the materialist, utilitarian economism that had come to dominate England sapped all that is vital out of life, leading to human catastrophe and both spiritual and moral decline. He viewed laissez-faire economics as an abnegation of responsibility: the ship of state must be steered. The gospel of mammon comes to replace God; the doctrine of “cash-payment” becomes the “universal sole nexus of man to man.”

The social bonds and moral unity of the medieval period (Carlyle points to the 12th century in Past and Present) were much preferable to the situation after industrialism. One issue with such a soul-sapping social environment is the “despair of finding any Heroes to govern you.” He saw democracy as an abomination and a symptom of the moral cowardice of the governing class. He had no patience for Parliament whatsoever: “Dost thou think that Willemus Conquestor would have tolerated ten years’ jargon, one hour’s jargon, on the propriety of killing Cotton-manufactures by partridge Corn-Laws?” To Carlyle, democracy is, as he put it in “The Present Time” (1850), “a bottomless volcano, or universal powder-mine of most inflammable mutinous chaotic elements.”

More than 150 years later, who can disagree with him?

Top image: Thomas Carlyle, 1854 (Robert Scott Tait / via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Leave a Reply