The Rabble-Rouser

Growing up in the 1950s, I used to read every day the Bridgeport Post, which was then a rock-ribbed Republican newspaper (it was acquired by the Hearst Corp. in 1992 and rebranded into the left-leaning Connecticut Post). I took up this habit because of my fondness for a particular columnist, who in 1941 won the Pulitzer Prize for exposing corrupt labor practices. He later denounced FDR and, even more sardonically, his busybody wife, Eleanor, who became known in his columns as “la Gran Boca.” This favorite columnist of my youth was James Westbrook Pegler (1894-1969), the son of a Minneapolis newspaper editor, who courted political controversy and who never backed down from assailing a leftist target.

It seems that Pegler is now mostly known through his enemies, who provide jaundiced portraits of his life and work. The entry for him in the Encyclopedia Britannica abounds in extravagant accusations, such as the now-routine but hardly well-demonstrated charge that Pegler engaged in vituperative statements against American Jews. I don’t remember those vituperations; and if memory serves, Pegler’s first wife, Julia Harpman, to whom he was married for 33 years until her death, was Jewish.

The present status of this eloquent columnist in our conservative establishment borders on nonexistence. Pegler is conspicuously absent from George H. Nash’s massive work, The Conservative Intellectual Movement in America Since 1945. Nash could have easily left out a multitude of lesser-known and rhetorically less brilliant figures to make room for Pegler.

In an article for the New Yorker in 2004, William F. Buckley Jr. tried to revive interest in Pegler. He approvingly quoted the liberal journalist Murray Kempton’s characterization of Pegler as “the common man with a grievance … one of the few American workingmen who have heroically and stubbornly struggled to remain class conscious.” Indeed, Pegler once said, “I claim authority to speak for the rabble because I am a member of the rabble in good standing.”

A leftist critic writing for Slate, Diane McWhorter, laced into both Pegler and his defender by charging that in the 1930s and ’40s Buckley’s subject had been “a leading popularizer of one of the most concerted antidemocratic crusades in this country’s history: the vicious backlash against the New Deal and the labor movement to which it gave legal protection.” The problem with this accusation is that it ignores the powers that organized labor had acquired before the New Deal, going back to the Progressive Era. It also emotively condemns the criticism that the New Deal elicited. Is it possible, one might ask, to disapprove of the New Deal without engaging in “vicious” behavior? Isn’t it also possible to reject the direction in which that project took our government and country without hating blue-collar workers?

Most contemporary writers refer to Pegler as a “right-wing populist.” He was that, but unlike our current populists, he was not particularly sympathetic to powerful workers’ unions and was very much concerned with the spread of international communism. Those were popular conservative positions in the 1940s and ’50s, when Pegler reached his zenith as a syndicated columnist. Pegler was not just a commentator but a serious newsman as well. His Pulitzer Prize-winning reporting revealed corruption in the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, whose union officials had siphoned off millions to Chicago mob bosses.

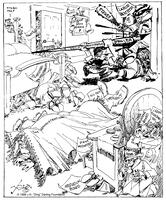

(J. N. “Ding” Darling / University of Iowa Libraries)

Pegler later made a name for himself as an acidulous critic of the civil rights movement. His most notorious tirade against Freedom Riders, written in 1961, can now be found on some leftist websites, with predictably unkind judgments. One needn’t defend every word of that diatribe to recognize in it elements of truth. Pegler was mocking those who aggravated social and political tensions thousands of miles from their homes out of a sense of moral importance. He considered these crusaders—mostly white liberals—to be troublemakers driven by “mawkish” sentiments. Making matters worse, they were becoming a common feature of contemporary American life. He wrote:

It is a mocking comment on the mawkish generosity of the American character that the bands of insipid futilities of the type called bleeding hearts can invade one of the finest American cities and arouse a howling national uproar of indignation, disgust, pity and shame. This the so-called freedom riders have done in Jackson, a really fine American city.

What Pegler may not have discerned was the will to power among leftist crusaders, who would eventually take over our deep state and cultural institutions. Many of these activists were “virtue signaling” to others in their social group without necessarily improving the condition of Southern blacks. One needn’t view Jackson in 1961 as “a really fine city,” and one may even find, as I do, its segregation laws a less-than-ideal situation for those affected by them. But looking at such focal points of the civil rights movement in the 1950s and ’60s as Selma, Alabama, one can’t help noticing how much worse they have become socioeconomically and physically since the civil rights revolution. Did the Freedom Riders do anything to help these places, as opposed to fattening their own resumes?

The Hoover Library in West Branch, Iowa, now houses the bulk of Pegler’s writings. Unbeknownst to most of his admirers and detractors, this controversial political pundit was also one of the most talented American sports writers of his time. His commentaries on athletes and sports events written for Scripps Howard between 1919 and 1925 are still worth reading for their vivid prose. His coverage of the 1928 Republican convention, done for the same news syndicate, reads just as powerfully as his earlier sports writing. It may have been as a result of his experience reporting the nomination of Herbert Hoover in 1928 that Pegler decided to turn his full-time attention to the political arena.

One of his series of columns that I read with special relish was produced during a visit to the Soviet Union in 1962. By that time, leftist intellectuals and journalists were hailing the “thaw” in Soviet politics and life; and according to my later college professors, a new generation of Russian leaders were helping us overcome our unreasonable distaste for communist countries. Since Pegler in the 1950s had been an effusive admirer of Joe McCarthy, it was strange that the Soviets invited him to visit their socialist society. But they did, and his printed responses were memorable. Pegler commented on the “rubbery chicken” he was served by his Soviet hosts, and he never let his readers forget how dingy and uncomfortable life in Soviet Russia really was.

For me, reading Pegler’s descriptions of Soviet life, which he probably was only allowed to view at its best, was reminiscent of my seeing a display of Soviet achievements at the New York Coliseum a few years earlier. I came away from that exhibit appalled by how unimpressive the “Soviet experiment” looked. My Hungarian immigrant father, who took me to that display, noticed that the Soviets’ model sewing machines looked more primitive than the ones that furriers in Budapest had used in the early 1930s. I myself was struck by how badly the suits worn by the Soviet guides were fitted; they looked as if they were bought on sale at an American discount store.

There are two very compelling reasons that today’s American right should view Pegler as a worthy model for their activities. One, he pioneered a style of written polemic that influenced the style of the American right, especially what is called the populist right. Traces of Pegler’s style can be found in Sam Francis’s columns, for example, and his influence on Francis was likely far more profound than that of H. L. Mencken, with whom Francis has been compared. Whereas Mencken mocked small-town America as part of his hated “boobocracy,” Pegler, like Sam Francis and today’s populist right, celebrated the habits and institutions of “Middle America” and viewed them as a source of moral strength.

Pegler’s influence on the American right is far more widespread than is commonly realized, and affects those who are completely oblivious to it. In 2008, the mainstream media chided Alaska Governor Sarah Palin for inadvertently cribbing parts of a speech about the values of small-town America from one of Pegler’s columns. Not at all surprisingly, Palin had no idea who she had plagiarized. Would the media have yammered as stridently if Palin took her lines from Al Sharpton, Joy Reid, Maxine Waters, or some other black race hustler? I won’t wait for the answer.

Like Sam Francis, Pegler lived at a time when the culturally and governmentally driven call for socially engineered equality was already reaching a fever pitch, and both Francis and Pegler derided the advocates of this intrusive form of politics. I also noticed in reading the spirited commentaries of Murray Rothbard that they, too, reminded me of Pegler’s polemics. So did the pieces by other columnists for the Rothbard-Rockwell Report, for which I wrote in the 1990s. Unlike Palin, both Rothbard and Lew Rockwell knew who Pegler was and were likely conscious of his influence.

Today’s populists have fully embraced Pegler’s practice of mocking wayward elites. This may have been why Pegler was decisively thrown down the memory hole, while Mencken is still at least remembered by his detractors. Pegler conducted no-holds-barred assaults on powerful interests on the left and dealt with corruption in a furious manner. Demonstrating the effect he had in polite society, a cartoon from the 1940s depicts a formal event disrupted by tuxedoed men screaming at each other. A woman in the center of the image says, “All I did was mention Pegler!” Strangely enough, the post-Boomer right may be surprised to learn that they had this predecessor whom I grew up reading. So successfully has Pegler been forgotten by what passes for the right that he may have to be “rediscovered.”

Pegler’s attack style, however, led to unfortunate excess, particularly during the last few years of his life, when his many ailments probably worsened his proverbial irritability. His attack on writer Quentin Reynolds led to a costly libel suit against him and his publishers, as a jury awarded Reynolds $175,001 in damages. In 1962, he lost his contract with King Features Syndicate, owned by Hearst, after he criticized Hearst executives. As a result, his late writing appeared only sporadically in various publications. And, in 1965, referring to Robert F. Kennedy, Pegler wrote, “Some white patriot of the Southern tier will spatter his spoonful of brains in public premises before the snow flies.” Kennedy was assassinated three years later, though by a Palestinian Arab.

Nevertheless, Pegler accurately foresaw that America would walk off a cliff under the direction of an increasingly powerful left. No one would question that Pegler conveyed his warning in an often “immoderate” fashion, but then he was not the kind of person who would be asked to write for the Wall Street Journal or be invited to a birthday party for George Will.

Throughout all those years when the timidity of “respectable” conservatives and their yapping about finding “common ground” with the more determined left made me queasy, I thought of how Pegler would be reacting. Naturally, with fire and brimstone. For all those invectives he produced with less than the requisite care, his forcefulness in speaking out as a member of what Sam Francis described as “Middle America” is what I admired most about him.

Leave a Reply