“Nobody’s Respectable Negro”

Zora Neale Hurston was a rare bird. A rara avis in terris, nigroque simillima cygno—“a rare bird on this earth, similar to a black swan,” in Juvenal’s phrase—whose larger-than-life persona was a fabulous concoction of myth and reality. Virtually from the moment she emerged from obscurity as a Southern writer and anthropologist to a published author, she was recognized as a singular talent. But, as her New York publishers and patrons soon learned, she was a talent whose mercurial energies could not easily be confined within safe, liberal channels. She had no patience for the posturing about “black consciousness” by Harlem’s literary and intellectual elite—those she dubbed the “Nigeratti.” Neither had she any compunction about calling out the often-hypocritical racism of white Northerners who pretended to be friends of the Negro.

After three decades of success as a writer of fiction and student of black American folklore (roughly between 1926 and 1955), Hurston sank back into the obscurity from which she came. In the end, she was buried a pauper in an unmarked grave in Florida, the place she called home. More than two decades after her death, she was rediscovered. Today, she is something of an American icon. Virtually everything she ever wrote is now in print, including a number of titles that were never published in her lifetime, and she has become the focus of a contentious academic debate about the significance of her work and her place in African American culture. Almost everyone acknowledges (when they don’t ignore it altogether) her open affinity for the libertarian wing of the Old Right and her cultural conservatism. More often than not, that inconvenient truth is swept aside or explained away in an attempt to refashion her as a feminist and a powerful advocate for black civil rights. Both of these claims are largely, if not entirely, false.

Hurston’s brief 1928 memoir essay, “How It Feels to Be Colored Me,” memorably illustrates both her lifelong antipathy to “race consciousness” and her tendency to mask certain aspects of her background that might detract from her carefully crafted public persona. She states that she was born and raised until the age of 13 in Eatonville, Florida—America’s first all-black town—though, in fact, she was born in Notasulga, Alabama, in 1891, to a sharecropper father, John Hurston, and a schoolteacher mother, Lucy, whose family were a notch more elevated in the black social hierarchy. Only three years later did her parents move the family to Eatonville, where her father, who had also been a preacher in Alabama, accepted a position as pastor of a local Baptist church. But most of this is concealed in the memoir. Indeed, her parents are never mentioned, though John would later become mayor of the town for three terms.

What she offers the reader instead is a portrait of a little girl who was the joyful child of the town itself—she was “everybody’s Zora.” What she loved best was to perch on the family front porch and perform for the travelers who passed in their cars or wagons. It was “gallery seat … for a born first-nighter,” she wrote. The passing Northerners especially liked to hear her “speak pieces,” sing, and “dance the parse-me-la” (a popular ragtime step of the day). Much to the chagrin of her family and neighbors, “who deplored any joyful tendencies in me,” she would accept silver coins from these strangers.

In those years, she was oblivious to racial differences. While she no doubt noticed skin color, whites and blacks seemed essentially the same to her. About the time she turned 13, however, her beloved mother died, and her father sent her away to Jacksonville to live with her sister and attend school. There, she discovered that she was no longer “Zora of Orange County,” but merely a “little colored girl … a fast brown—warranted not to rub or run.”

Even so, this expulsion into a world where racial differences mattered did not become an opportunity for self-pity. Shifting abruptly from the past to the present tense, she announces (now from an adult perspective), “But I am not tragically colored. There is no great sorrow damned up in my soul…. I do not mind at all. I do not belong to the sobbing school of Negrohood who hold that nature has somehow given them a raw deal.”

By “sobbing school,” she refers to those African Americans who were crippled by racial resentment, but more particularly to those leaders, like W.E.B. Dubois and many others, who were in the 1920s pushing a “black consciousness” agenda. Controversially, she declared, “Slavery is the price I paid for civilization.” She means, of course, that it was the price she paid through her ancestors, but she doesn’t seem terribly put out by their suffering. “The choice was not with me,” she bluntly states. In any case, she has no “time for weeping,” for she is “too busy sharpening [her] oyster shell.”

Yet this rejection of race consciousness is not a rejection of her color or ethnicity. Later in the memoir, she celebrates her African origins in a scene in a Harlem jazz club, where she has gone to hear a popular band with a white male friend. When the band hits its stride, the music

rears on its hind legs and attacks the tonal veil with primitive fury, rending it, clawing it until it breaks through to the jungle beyond. I follow those heathen—follow them exultingly. I dance wildly inside myself; I yell within, I whoop; I shake my assegai above my head, I hurl it true to the mark yeeeeooww! I am in the jungle and living in the jungle way. My face is painted red and yellow and my body is painted blue. My pulse is throbbing like a war drum. I want to slaughter something—give pain, give death to what, I do not know.

When this moment of ecstasy passes, she sees that her white friend seems unmoved by her passion. In such moments she feels her blackness acutely: “He is so pale and I am so colored.” But there is no shame or embarrassment in her tone. However, she adds, often “I have no race, I am me. When I set my hat at a certain angle and saunter down Seventh Avenue, Harlem City, feeling as snooty as the lions in front of the Forty-Second Street Library …” then “[t]he cosmic Zora emerges. I belong to no race nor time. I am the eternal feminine with its string of beads.”

By the time that she wrote “How It Feels…” Hurston had, after the “wandering years” that followed her exile from Eatonville, completed degrees at Howard University, where she first met the African-American philosopher Alain LeRoy Locke, and at Barnard College in New York. At Columbia University, she studied anthropology under Franz Boas, who supported her ethnographic ambitions.

In New York, she also established connections with a number of writers and artists who were already associated with what came to be called the Harlem Renaissance, among them Langston Hughes and Countee Cullen. But though she valued such friendships, she was unable to embrace the communist sympathies of Hughes and Locke or their self-proclaimed solidarity with the oppressed blacks of the South. For, as she saw things, such men had little or no actual knowledge of the lives of those “farthest down,” as she called the Southern negroes whose ignorance and desperate poverty she had come to know well and whom she refused to think of as merely “victims” of white oppression. Leftist writers and critics insisted that to portray Southern blacks outside the framework of white oppression and violence—that is, in all their genuine complexity—was to abandon the cause of full equality.

The “Nigeratti” had long since severed their ties with the South and had little interest in the thousands of small black communities whose inhabitants, despite their economic misfortunes, were culturally rich. As an ethnographer, it was that culture—its dialects, its folklore, its religiosity, its rituals—that she hoped to record. With encouragement from Boas, she returned to the South in 1928 in hopes of collecting materials for publication. In Florida, she lived among the turpentine camps, essentially small villages that had grown up around turpentine distilleries, and among the sawmills, where former slaves and their sons and daughters toiled. There, she conducted interviews, collected tales, participated in worship services, and absorbed the local customs.

The following year, she went to New Orleans, where she lived in and studied communities where Hoodoo was practiced. Violating the usual ethnographic practice, she was both an observer of and a participant in Hoodoo rituals. By the time of her return to New York, she had recorded hundreds of tales, transcribed sermons, and compiled reams of notes—enough to provide fodder for several books. In 1931, she published a scholarly article in the Journal of American Folklore titled “Hoodoo in America,” as well as a number of pieces on negro dialect and spirituals in the 1934 classic anthology of black culture, Negro.

Also in 1934, she published two major works that had evolved out of her fieldwork: Mules and Men, a collection of folktales, and Jonah’s Gourd Vine, her first novel.

Critics generally regard Mules and Men as one of the best collections of Southern black folklore, but they’ve also criticized it because of the method Hurston employed in writing the book. In fact, the book purposely reflects the methods she used to gather the material in the first place. Again eschewing the role of the detached observer, she worked to establish almost familial relationships with her “subjects,” becoming a part of their lives.

In Polk County, Florida, where she had gone because the mill camps there attracted workmen, their wives, and families from all over the South, she fully expected some difficulty gaining acceptance. Indeed, she encountered “a noticeable disposition to fend me off.” She was, of course, a stranger, and because she had arrived in what seemed to them a shiny car, they suspected her of being a detective. Since “most of them were fugitives from the law or had done time…” they were wary of her. When she learned of their suspicions, she immediately began letting on that she was herself a fugitive, “wanted” in Miami for bootlegging.

beating the hountar drum.

Zora’s protectress in Polk County was a woman known as “Babe,” who had apparently shot and killed her husband two years earlier. She had then altered her appearance and eluded the law for months before being captured and jailed in Barstow, though she was soon allowed to return home. Hurston’s sly humor, so often on display in these pages, is evident in her observation that “women are punished in these parts for killing men, but only if they exceed the quota. I don’t remember what the quota is.” While Hurston doesn’t explicitly say so, the underlying suggestion is that Babe may have had good reason to shoot her husband. Such acts of violence were not uncommon among the “blacks farthest down,” and Hurston never flinches from or conceals that reality. Nor does she use it as a pretext for identifying white oppression as its underlying cause. To do so would deny the perpetrators agency.

As Tiffany Ruby Patterson notes in Zora Neale Hurston and a History of Southern Life (2005), black writers in Hurton’s day faced a dilemma: To what extent should they focus on the racial caste system and the struggle for black equality? On this question, there were two schools of opinion. W.E.B. Du Bois, Langston Hughes, Richard Wright, and others contended that the political purpose (in fiction or otherwise) must be paramount. This was a point stressed by Du Bois over several years, but he spun it most memorably in his 1926 essay “Criteria of Negro Art,” where he argued that, for the Negro at least, “all art must be propaganda…. [W]hatever art I have for writing has been used for propaganda for gaining the right[s] of black folk. I do not give a damn about any art that is not used for propaganda.”

As it happens, though Du Bois was primarily a sociologist, he wrote several novels, including Black Princess (1928), a work concerned with the lives of what he termed the “talented tenth”—that is, the rising black elite. His biographer, David Levering Lewis, described the novel as “a sort of black Comédie Humaine [Balzac’s 19th-century collection of stories about French society]… with strong women and decisive, sensitive men”—in short, idealized models of what upwardly mobile blacks should aspire to become.

By contrast, the African-American classicist W. S. Scarborough argued in his essay “The Educated Negro and His Mission” (1903) that the black writer’s mission should be “to portray the Negro’s loves and hates, his hopes and fears, his ambitions, his whole life in such a way that the world will weep and laugh … finding the touch that will make all nature kin.” In other words, black lives should be depicted with an artistry unburdened by propaganda.

This was Hurston’s artistic credo. No aspect of Negro cultural life was without value—the dialects (or “idiom” to use her preferred term), the tales and superstitions, the music, the preaching, the “conjure” rituals, and much more. Above all, as she wrote in her 1937 essay “Art and Such” (in part a response to Richard Wright’s critical review of her novel Their Eyes Were Watching God), the negro must be represented as an individual, as he really exists, “not as another tragic unit of the Race.” Unfortunately, she laments, the negro novelist is imprisoned within his consciousness of the “Race problem.” The dismal effect had been “to fix activities in a mold that precluded originality….”

That novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God, was Hurston’s most accomplished work. It was the first black novel to shatter the race-consciousness mold. Its originality is beyond question; its mastery of the Southern idiom—both black and white—equals that of her contemporary, William Faulkner; and its characters run the gamut from sordid to heroic.

Set in Florida, as are most of her novels and short stories, Their Eyes chronicles several decades in the life of a young black woman, Janie, whose quest to find a man worthy of her love ultimately leads her to a wandering gambler by the name of Tea Cake, who is a brilliant symbolic representation, rooted in African mysticism, of the rejuvenating power of nature. In many respects, Janie is Hurston’s literary counterpart, for she is a griot, or storyteller, whose verbal prowess is her most distinguishing attribute. In Tea Cake she finds her spiritual equal, but their time together is cut short when a hurricane-driven flood of biblical proportions overwhelms the shantytown near Lake Okeechobee where they had found a kind of refuge. When a rabid dog bites Tea Cake in the midst of the storm, Tea Cake goes mad. When he attempts to kill Janie in his madness, she is forced to defend herself with a rifle. Tea Cake’s death results in a trial for murder, but like Babe in Mules and Men, Janie escapes conviction when a jury deems her husband’s death both an “accident” and an act of mercy—though it was neither.

But such a plot synopsis doesn’t begin to capture the riches of this novel, which Hurston suffused with the folkloric traditions that she had studied for years and with dozens of passages of memorable comedy, including tall tales, hilarious verbal repartee, mimicry, and the grotesque (such as a scene in the first half of the novel in which a local preacher extols the virtues of a beloved mule as he stands atop its bloated corpse). More importantly, Janie’s development as a character reveals her growth in wisdom and strength—particularly in the power of endurance, which is a crucial aspect of the Southern moral code.

Endurance, as understood by Hurston and Faulkner (and many other Southern writers) stands for a paradoxical combination of pride and humility, a virtue born out of suffering and tragedy and at least implicitly out of faith in an overriding providential order. Such an order is strongly suggested in the passage from whence the novel takes its name. As the catastrophic flood overruns the banks of the Okeechobee and rises towards the cabins of the huddled residents of the nameless shantytown, Janie and Tea Cake “sat in company with the others in other shanties, their eyes straining against crude walls and their souls asking if He meant to measure their puny might against His. They seemed to be staring at the dark, but their eyes were watching God.”

For women to pretend that they possess masculine qualities may be “costing [them] more than they care to admit,” Hurston wrote. As a result, she concludes, “the nation is strewn with female neurotics from end to end.”

After academics rediscovered Hurston’s oeuvre in the 1970s, they rehabilitated her as a feminist author, and that is largely how she is taught in universities today. Their Eyes is routinely touted as a feminist vision of a strong woman who struggles against controlling male dominance and violence. Certainly, Janie is a strong woman, but the equality she seeks is not one stripped of the essential complementarity of male and female. She is both strong and submissive, independent and yet sacrificially devoted to Tea Cake, the man who has given her the gift of new life.

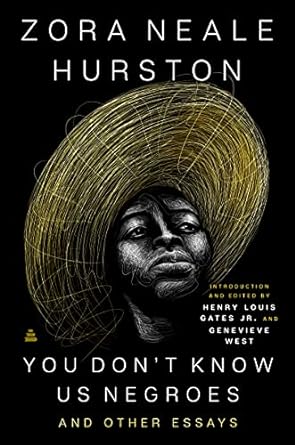

Thankfully, at least one critic, Jennifer Jordan, has recognized the “unsupportable notion that the novel is an appropriate fictional representation of the concerns and attitudes of modern black feminism.” That Hurston was unimpressed by feminist claims for full equality in her own day is evident in her essay “The Lost Keys of Glory,” which remained unpublished before her death but is now available in the 2022 collection of Hurston’s work, You Don’t Know Us Negroes and Other Essays (2022). This essay begins with a fable taken out of Mules and Men and concludes with some observations on the folly of women who seek to compete with men in public life. She asks, “How did men gain control in the first place?” She answers that it is not simply their greater physical strength but their capacity for “detachment” from emotional turmoil and their sustained drive to succeed. For women to pretend they possess masculine qualities may be “costing [them] more than they care to admit,” Hurston wrote. As a result, she concludes, “the nation is strewn with female neurotics from end to end.”

Finally, despite the efforts of the liberal-left cultural monopoly to claim Hurston as one of their own, any serious examination of her work and her political affiliations must conclude that she was very much a woman of the right. From the late 1920s until the end of her life, she took a public stand on a number of issues that established her as a fellow-traveler with the Old Right:

- She was vehemently anti-communist before and during the Cold War era.

- In the years before World War II she was an America First anti-interventionist; she supported Sen. Robert A. Taft of Ohio in his failed 1940 presidential campaign.

- In Florida, though a Republican, she campaigned for “Gorgeous” George Smathers in his successful bid to unseat Sen. Claude “Red” Pepper in the 1950 Democrat primary, largely because the latter had been a FDR toady and an advocate of rapprochement with the Soviets (going so far as to cozy up to Stalin on a trip to Moscow).

- She was consistently critical of the New Deal, opposing its expansion of federal power and its burgeoning bureaucratic apparatus.

- She harshly criticized the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision for robbing local communities—especially black communities—of their right to control their children’s education.

More generally, like Booker T. Washington, Hurston loathed the patronizing policies of Northern liberals that, if unopposed, would reduce poor Southern blacks to a condition of perpetual dependence on social welfare programs. As she was fond of saying, “Them’s my sentiments and I am sticking by them.”

Leave a Reply