In the early 50’s, Philip Graham of the Washington Post tried to hire James Reston away from the New York Times at twice the coins the Sulzbergers were dispensing. Thanks, but no thanks, Reston said-and kept saying whenever his friend Graham sought to renew the discussion. The Times family was James Reston’s family, professionally speaking. He was flesh of its flesh and hone of its bone, which is why his career there rose to the heights: head of the Washington bureau, executive editor, columnist since time out of mind, holder of 28 honorary degrees, winner of two Pulitzer Prizes for reporting.

Newspapers, in contrast with yogurt shops and insurance companies, have personalities of their own. These normally are imprinted by owners who can sec beyond the profit and loss statement and who feel the stirrings of Mission. The homogenization of American news papers is due as much as anything else to the loss of local ownership, but that’s another story.

The Times, still family-owned, is the student body president of newspapers smart, knowing, given on occasion to self-importance and hectoring; not flashy, not glitzy, inclined to stodginess but withal steady and dutiful, with an inbred sense of citizenship and responsibility, and not without the capacity for adaptation and change. Ditto Scotty Reston. Neither institution-Scotty or the Times-is to everybody’s taste, but there is much to be said for both, and in any case they’ve been around since Methusaleh.

The present book, written in Reston’s old age, though not his dotage, should be his grand view of the 20th century, its journalism, its politics, its character, but I hate to say that this frequently engaging book falls short on these terms. Deadline displays the “and then” quality often found in newspaper memoirs. There’s not much overview here. Events follow each other sequentially. So-and so became President; then someone else took over. Such-and-such laws were passed during this time. Newspapers are every day stitched together in this workmanlike fashion; the habit becomes numbing for those who think in day-to day rather than era-to-era fashion.

Scotty Reston, in the personal sense, transcends eras. He has endearingly old fashioned qualities and ideals. “I think it’s better to take things with gratitude rather than for granted,” he writes aphoristically. I’m not sure what I believe about the ultimate questions of life and death, but I believe in believing. I think the world is too complicated to be governed by ideology, and that there are many roads to the Promised Land and many sides to truth. Therefore, I prefer courtesy to dogmatism and patience to judgment.” He esteems the work ethic, personal integrity, the family unit, the marriage bond-and Sally Reston, to whom he was bonded more than half a century ago. He seldom misses an opportunity to pay his wife tribute. Their love, profound and touching, is no bad thing to read about in the age of Warren Beatty and Antoinette Bening.

James Reston was born a Lowland Scot in 1909. After World War I, his family emigrated to Dayton, Ohio. He loved then, and still does, the land that opened its door to the Reston family. His parents’ Calvinist faith was the formative element in his character, as he is fond of reminding readers. “The atmosphere in our family,” he writes, “was one of intimidating piety, austerity, and authority, respectful of religion, education, and hard work. There was never a drop of whiskey or a pinch of tobacco in our house, and while sex was tolerated as a necessary evil, I retain the impression that my folks thought anything so popular had to be dangerous if not downright wicked.”

Reston along the way acquired impressive patrons-first, James Cox, owner of the Dayton, Ohio, newspaper and 1920 Democratic presidential candidate, who hired him as a sportswriter; subsequently, Arthur Hays Sulzberger, who plucked him out of the New York Times‘ London bureau in 1940 and set him down in Arthur Krock’s Washington bureau. The Times‘ Jewish publisher had recognized the young Scots Calvinist reporter as a natural member of the paper’s extended family. “My boss and dear friend,” Reston called Sulzberger.

In Washington Scotty Reston’s career reached fulfillment. He took over the bureau from Krock in 1953. He was an insider of the insiders. He claims never to have flown into Washington “with out a happy sense of coming home.” A late 60’s stint in New York as executive editor was “doleful.” He was a bird out of the reportorial cage. This bondage passed, and soon the column was again absorbing most of his energies. He wrote regularly until formal retirement in 1987; more and more as a gray presence, a Grand Old Man; sly, cutting, observant, puckish, an Establishment liberal to his fingertips but never a tub-thumper like various other Times columnists. Reston has at bottom a wry Scottish humor. He lacks Anthony Lewis’s nonstop indignation, Tom Wicker’s dourness, Abe Rosenthal’s ethnocentricity.

Like all pundits who write longer, or more, than is good for them, Reston could be wildly wrong. I recall the column in which he declared with ill-concealed satisfaction that the Republicans, by nominating Ronald Reagan, were giving Jimmy Carter his wish: an ideologue he could beat like a drum. This was Reston at his most oracular-a family habit around the Times but, intellectually, a dangerous one. Reston never did admire Reagan, whom he regards as an artificer; still he credits the former President, backhandedly, with schlepping and sleeping through a successful presidency.

I think we can take this in good part from a good Calvinist unashamed to trumpet, in the teeth of an otherwise minded age, his love of America, his family, his one and only wife. Scotty Reston has met his last deadline with honor, if not with the distinction we might have expected.

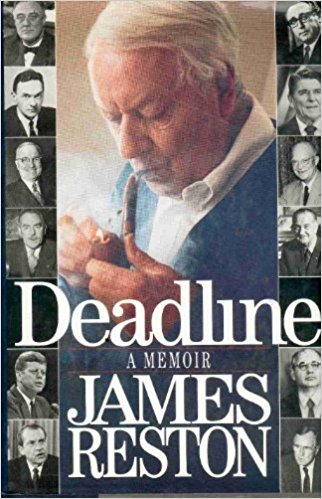

[Deadline: A Memoir, by James Reston (New York: Random House) 525 pp., $25.00]

Leave a Reply