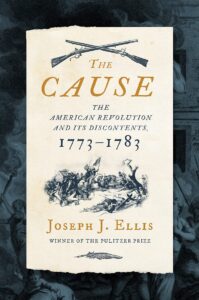

The Cause: The American Revolution and Its Discontents, 1773-1783

by Joseph J. Ellis

Liveright

400 pp., $30.00

The term “American Revolution” was not used by the Founding Fathers, but adopted by later generations. The British called the dispute “the American rebellion,” while on our side of the Atlantic, it was referred to as “The Cause,” because at that time, the colonists in rebellion had no American national identity and referred to their home state—be it Virginia, New York, or New England—as “their country.”

As Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Joseph Ellis describes in The Cause, all through the struggle for American independence, and even afterward, “there was always far more emphasis on pluribus [“the many”] than unum. [“the one”].”

Along with having no national identity, most of the participants in the cause were not revolutionaries. Ellis writes:

The earliest and most articulate advocates of the cause insisted that they were not proposing a revolution. Quite the contrary, it was the British government that was attempting to impose a revolutionary change in the structure of the British empire by insisting that Parliament was empowered to tax and legislate for the colonies without their consent.

Ellis stresses that the American rebellion was a “prudent revolution,” wherein participants believed more in gradual evolution than in radical change. Those in rebellion might have appreciated Thomas Paine’s Common Sense for its fine prose, but rebels like John Adams and many others did not believe that mankind had it in its power, as Paine wrote, “to begin the world over again.”

Paine envisioned a huge nationally elected assembly of “representatives from all the newly created states, no fewer than 390 delegates, who would meet annually to pass all laws on the basis of a three-fifths majority.” Wary of Paine, Adams saw the utter impracticality of this scheme, later tried by French revolutionaries, with disastrous consequences. To Adams it was obvious that a single ruling legislative body, like one-man rule, ends in despotism and that power should be divided into different branches, with checks and balances on each.

Unlike Paine, Adams had no illusion that the creation of a more democratic government would solve the problems of human nature. As Ellis wrote in Passionate Sage (1993), Adams believed that the source of ailing humanity was innate to men and women, in “their jealousy and passion for distinction.”

The 13 colonies were really only united by the principle of the cause: opposition to the British. By examining the American rebellion through the vantage point of that motivating factor, Ellis opens up a new perspective on the events of 1773-1783. The book focuses on various episodes of that fight for independence—from Philadelphia to New York to Valley Forge to the Chesapeake—as the cause survived and developed.

The roots of America’s independence began with the British victory over the French in the Seven Years’ War (1756-63). France lost her North American possession, Canada, and England doubled the size of its dominion in America, but the war was costly, leaving the British with £133 million in debt.

Previously, Britain’s relationship with her colonies was one of benign neglect. Now with a new empire, the English decided to put their administrative house in order. New laws and taxes were imposed on the colonies to help pay for the debt, and a great resentment consequently arose.

The colonists insisted that Parliament had no authority to tax them. Events escalated. In 1774, colonists disguised as Mohawk Indians dumped the “vile weed” of taxed tea into Boston Harbor. The Port of Boston was closed, and a military governor, General Thomas Gage, was placed in command of Massachusetts. King George wrote to Lord North, “The dye is now cast, the colonies must either submit or triumph.”

Ellis understands that war is an extension of politics and brings this out brilliantly in his chapter, “The Escape,” assaying the disastrous New York campaign of 1776, which could have ended the American cause just when it was getting started. With its many islands and inlets, New York was a difficult place to defend or to capture. “What to do with this city, I own, puzzles me, it is so encircled with navigable water that whoever commands the Sea commands the town,” General Henry Lee wrote at the time.

What was Washington thinking in defending a place he knew to be indefensible? Ellis answers that “Washington was not choosing to defend New York. He was obeying an order from his civilian superiors to do so.” The decision was based on political rather than military concerns.

On the English side, the Howe brothers, Admiral Richard and General William, were Whigs, known to be friendly to the colonial cause, who thought the war was a mistake. They only accepted the command

on the condition they be granted diplomatic authority to offer generous terms for reconciliation after delivering a sufficiently devastating military defeat to convince the Americans their cause was hopeless.

General Howe, who took Bunker Hill in 1775 at heavy losses, was reluctant to order a frontal assault on the rebel fortifications in New York. But this does not explain his decision to halt his troops at Gowanus Heights. Colonial General Israel Putnam said, “Howe had our whole army in his power” and concluded, “General Howe is either our friend or no general.” Howe’s delay allowed Washington, under cover of fog, to cross the East River and escape with a large part of his army intact, keeping the rebel cause alive. British General Clinton wrote of the day’s events, “Howe lost as good a chance as Britain ever had of winning the war in a stroke.”

At Valley Forge, the rebel army not only survived the bitterly cold winter of 1777, but actually regrouped with the support of Prussian General Friedrich Wilhelm Ludolf Gerhard Augustin Louis von Steuben. On his chest he displayed as many medals as he had names. During that winter, von Steuben endlessly trained and drilled the army into a disciplined professional fighting force. Writing to a friend back home, von Steuben made interesting, astute observations on the character of the American soldier, so different from his European counterpart:

The genius of this nation is not in the least to be compared with that of Prussians, Austrians, or French. You say to your soldier, ‘Do this,’ and he doeth it. But I am obliged to say, ‘This is the reason you ought to do that,’ and then he does it.

Ellis tells not only the stories of those involved in the cause but also those of its discontents—namely, Native Americans and slaves. At the end of each chapter he has an interesting, short, synoptic profile of various men and women who took part in the struggle for and against independence: Joshua Loring, a Tory; Mercy Otis Warren, a writer; George Washington’s runaway slave, Harry Washington, who fought with the British army; Catharine Littlefield Greene, wife of General Greene; Joseph Brant, the great Mohawk chief; William (Billy) Lee, an indispensable aide and slave to George Washington; and Joseph Plumb Martin, a common revolutionary soldier whose memoir, Private Yankee Doodle, is a treasure to historians.

Ellis’s book is insightful, disclosing things often overlooked about the war for independence. We forget how vicious and bloody it was, especially in the countryside:

British foraging patrols, especially Hessian and loyalist troops, often gave no quarter, and presumed that plunder and rape were privileges of the profession.… In fact, more Americans died per capita in the war for independence than in any war in American history save the Civil War.

Ellis is a superb historian whose books on the Founding Fathers are a joy to read. He elevates the craft of history into a form of literature, but he is also a scholar—a product of the academy before it degenerated into a degree-granting bureaucracy. The book begins with a great quotation from historian Herbert Butterfield:

Real historical understanding is not achieved by the subordination of the past to the present, but rather by … attempting to see life with the eyes of another century than our own.

The Cause is one of those books to help us do just that.

Top image: Washington’s triumphal entry into New York, Nov. 25th, 1783 (Christian Inger, lithographer; P.S. Duval & Son. / public domain)

Leave a Reply