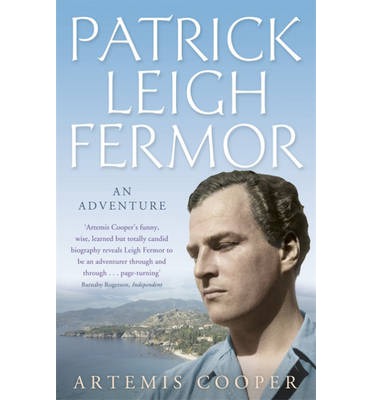

Even at first dip, this book gives the impression of being unreadable to any but the tweediest Anglophile. There are still such people in the world, you know, and some of them have even been born in Britain. For them, hearing the names “Lady Diana Cooper” or “St. Pancras” is like a drop of lime juice for a man with scurvy. At once they feel better.

The legendary Diana Cooper, incidentally, was the author’s grandmother, while St. Pancras is the district of London where the subject of this biography was born in 1915 to a member of the Indian Civil Service, a geologist stationed in Calcutta, and a rather volatile dame who divorced him soon after and returned to live in England. This is already quite boring, but if you add to it the village of Weedon Bec in Northamptonshire, a vicarage cottage in Dodford, and schools for the young ’un with names like Oundle, Haileybury, and St. Piran’s, it becomes clear why anyone but a Limey wannabe would bin this thing after the first 50 pages.

A certified product of the British middle class, Patrick Leigh Fermor, or Paddy, as he styled himself, had a clever idea as soon as he had come of age. Unable to get into university, regarded with anxiety by his divorced parents, and having neither independent means nor useful connections, the teenager decided to take a longish walk—from London to Istanbul, to be exact. The year was 1933, Hitler was taking power in Germany, Europe reeked of war, but none of this could stop young Paddy. A good third of this biography recounts in painstaking detail his experiences during the subsequent 386 days, as he crossed a dozen national frontiers to arrive in Turkey, yet another country on the continent of Eurasia of which, apparently, he knew little.

The journey reveals two things. One is Paddy’s prodigious knack for what we ought to be forthright and call social climbing. While the actual funding of the escapade came in the form of an admittedly modest allowance from his father—£4, something like $400 in today’s money, waiting for him on the first of the month at British consulates along the way—it would be rash to infer that the adventurous climber managed to arrive in Istanbul thanks to a sturdy pair of “hobnailed boots” on his youthful feet. Rather, letters of introduction, of which he would perspicaciously avail himself at every stage of his pilgrimage, opened the doors to castles, rather than barns, where cigars and brandies, rather than humble lodging, were to be had aplenty.

The other revelation for the reader of this book is the phenomenal, and eventually almost grotesque, superficiality that is arguably an inalienable characteristic of the British amateur in every walk of life. Now, I realize that the hero of this biography was only 18 when he set out to traverse the Continent; and that almost any other youth in his situation would have been nearly as ignorant of Europe’s languages, politics, and history as he was. Yet it still boggles the mind to hear Paddy sigh, over and over again, at the sight of this church or that mountain, that he wished he had known “more” about it. It’s all right to be clueless, certainly, or even fundamentally ignorant; but to pore over the scholarly biography of somebody who obviously regarded his own fundamental ignorance as a minor hitch, rather than as a major impediment, is a little hard on the nerves. Unless, of course, like the author of this biography, one is apt to see in rank superficiality a freedom of the spirit and a joie de vivre.

To London Paddy returned with Continental connections, one or two actually convertible to a journalistic or literary entrée, though one gets the creeping sensation that the golden boy came home not so much to write as to live the literary life—that is to say, to strut, to charm, to drink, and to recount or embellish all the marvellous adventures that had fallen to his share in Europe. God alone knows how these frolics might have ended—in all likelihood neither Lady Diana nor her granddaughter, to say nothing of us, denizens of another benighted century, would have heard the name Fermor—had not an unexpected boon to adventurers everywhere arrived in the form of World War II.

It is at this juncture that Paddy the man’s amateurishness, which merely got on one’s nerves as one regarded Paddy the boy, acquires a dimension that can only be described as surreal. Now nearly 30 and a fully fledged intelligence officer, he was posted to Crete, occupied jointly by the Germans and the Italians, with the task of organizing and coordinating the resistance. This secret and, admittedly, dangerous mission culminated in April 1944, a full eight months after the Italian Armistice and the turning of the tide at Stalingrad, with an action as reckless as it was senseless. Paddy, together with a dirty dozen of Cretan conspirators—one of whom, incidentally, he killed by mistake while playing with his gun—abducted a German general and spirited him off the island to the satisfaction, mainly, of the BBC. General Kreipe’s reaction is worth quoting: “Tell me, Major,” said the German to his abductor, “what is the object of this hussar stunt?” The biographer is honest enough to comment: “Paddy had to admit that there was no easy answer to that question.”

Actually, there is. No sooner is the war over than Paddy, predictably, is on a jubilant lecture tour through Greece, under the auspices of a body no less formidable than the British Council, in the course of which he again recounts and embroiders adventures he lately embarked on, this time round, ostensibly, in defense of King and country. Back in London there is much dining out on the same fare, and before long Paddy charms the pants off a publisher no less august than John Murray, whose forefathers at the firm, a Romantic age earlier, nurtured that other great hankerer after the liberty of Greece, Lord Byron, with whom Paddy is inevitably compared.

I ought to sign off with a confession. With the exception of what is quoted here and there by his biographer, I have not read a single line of the widely lionized writer that Paddy—married to a viscount’s daughter and dividing his time between fancy Gloucestershire and the exotic Peloponnese—would become in times of peace and prosperity. It appears that the youthful amble across Europe produced not one, but three of his best-known books, A Time of Gifts (1977), Between the Woods and the Water (1986), and The Broken Road: From the Iron Gates to Mount Athos (2014), and after learning from his biographer of the precise circumstances of their gestation I very much doubt that I shall ever pick up any of them.

there by his biographer, I have not read a single line of the widely lionized writer that Paddy—married to a viscount’s daughter and dividing his time between fancy Gloucestershire and the exotic Peloponnese—would become in times of peace and prosperity. It appears that the youthful amble across Europe produced not one, but three of his best-known books, A Time of Gifts (1977), Between the Woods and the Water (1986), and The Broken Road: From the Iron Gates to Mount Athos (2014), and after learning from his biographer of the precise circumstances of their gestation I very much doubt that I shall ever pick up any of them.

When Fermor died in 2011, a New York Times obituary eulogized him as “a cross between Indiana Jones, James Bond and Graham Greene.” I would say that of these three, if one is to judge by Artemis Cooper’s biography, at most two are in evidence.

Leave a Reply